Daily Life In Colonial Latin America (4 page)

Read Daily Life In Colonial Latin America Online

Authors: Ann Jefferson

In the scenario envisioned by the Europeans, the native

peoples were to serve as workers, as indeed most of them had in the

pre-Columbian period, so the Europeans organized systems of labor to control

the population and employ their labor in the extraction of the natural

resources of the newly acquired territories. This is the origin of the racial

hierarchy that would play a fundamental role in structuring Latin America

during the colonial period, as the physical appearance of the native

populations and the laborers brought from Africa served to identify them and

tie them to their status as laborers. Anyone who looked like an Indian or an

African was therefore assumed to be part of the laboring population and tracked

accordingly. Given this assumption, the burden of proof fell on any person of

Indian or African appearance who was

not

a tribute-paying village

laborer or an enslaved worker to prove his status as a free person.

Nothing about daily life can be understood outside of the

racial and ethnic boundaries that defined everyone’s roles, responsibilities,

rights, and opportunities in colonial Latin America. Whether the discussion

focuses on material culture (i.e., clothing, personal possessions, houses and

their contents), choice of a marital partner, occupation, or social life, one’s

racial category was the key determinant. While individuals did sometimes escape

their category and rise in the social structure, the structure was set up to be

a rigid system that would have a place for everyone and keep everyone in his or

her place.

This race-based social structure made Latin America

paradoxically both the region of greatest mixing of peoples of diverse origins

in the world and a region in which a person’s color, or phenotype, defined his

or her life to an extremely high degree. This racialized social structure is

best seen as a construction by dominant groups determined to restrict access to

resources and political power in the face of challenges by subaltern groups.

The Europeans, both colonists and crowns, were organizing these newly

discovered territories for the extraction of wealth. In a period before the

invention of machines when work was performed by human energy, labor had to be

coerced or coaxed from people, lots of them. Race was the primary tool used to

distinguish those in control from those to be controlled. This is not to say

that those in the groups to be controlled meekly trooped off to meet their fate

. . . far from it. In fact, their rejection of the rules presents us with some

of the most interesting and inspiring stories in Latin American history. But

that comes later.

The Multiplication of Racial Categories

In the beginning, the racial division was clear and

straightforward because there were just two groups: those who came across the

ocean from Europe and the people who met them. While a few African servants

came with the Iberians, their numbers were small, and they were not

differentiated from the others who came from Europe. Unfortunately for the

neatness of this system, conditions on the ground soon changed. People lost no

time in muddling the categories by producing offspring that were the result of

sexual encounters across ethnic boundaries. There were several reasons for

this: women of the conquered peoples were treated as part of the booty of

conquest, taken by or given to the Christians. In Christian societies, where

sex was cast as sinful outside of marriage, men’s access to women was limited

by law and custom. So although women from Europe began to arrive in the

American colonies shortly after the first conquerors, their numbers were low,

and they were not necessarily available as sexual partners for European men.

The women of the conquered peoples were part of what was won in the wars of

conquest, as workers and sex objects or, in some cases, willing sexual partners

and, if not always legal wives, mothers of the next generation.

In addition, as recent research on the Puebloans of New

Mexico shows, some very different meanings could be attached to sexual

intercourse and its function in the universe. This Pueblo perspective sheds new

light on stories of indigenous women throwing themselves at the conquerors. It

suggests that while there was surely some, possibly substantial, degree of rape

and exploitation of women’s bodies against their will, as there is in any

military invasion, if we can step outside Christian teachings that associate

sex with sin and shame, we encounter the possibility, at least in the earliest

days of the colonial period, of women willingly engaging in sexual relations

with the new arrivals. According to one scholar, in some cultures of the First

Nations, this was done as a way for women to empower themselves and their

communities, and to divest the invaders of power to do harm.

The offspring of alliances between indigenous people and

those who had arrived from across the seas merged previously isolated

populations of Africans, Europeans, and native people and created a society of

castas,

a generic term applied by Spaniards to racially mixed peoples. These

mestizos,

mulatos,

and

zambos,

to give only the three most common labels

dreamed up by Spaniards to distinguish among various “types” of castas, began

to appear quite early in the colonial period, and their place in colonial

society was not as rigidly fixed as that of Indians and whites. Seeking to meet

their daily needs for food, shelter, clothing, love, and good times, these

racially mixed people challenged the rigidity of the social structure and found

ways to exploit its interstices, sometimes rising into the dominant groups.

Another factor that confused the racial hierarchy was that

some whites did not fall into the category of elites, either because they came

from marginalized economic groups in Europe and were not able to raise their

status in the New World, or because they lost status for reasons of luck,

health, or vice. Thus not all whites were at the top of the social structure,

although in general they had a better chance of getting there.

In any case, the Europeans found phenotype a useful tool in

their project of organizing a colonial society for the extraction of wealth

from what was to them a new world, and race would continue to play a crucial

role in the lives of Latin Americans long after the colonial period had ended.

Many would argue it still does.

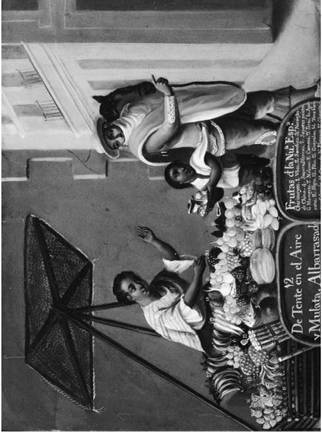

During the 18th century,

artworks known as casta paintings, depicting family groupings, generally

father, mother, and one child, became popular collectors’ items in Europe. The

point of these paintings was to show and label the results of racial and ethnic

mixtures occurring in New Spain. In this casta family of fruit sellers, the

child is learning the family business.

THE PATRIARCHAL EXTENDED FAMILY

The other key to understanding Latin American history is

the patriarchal extended family. Even today, many, it might even be fair to say

most, Latin Americans gain access to resources, meaning a place to live,

employment, or a marriage partner, through exploiting family relationships.

What might be seen as nepotism in another region of the world is often viewed

in Latin America as simply the best way to get things done. When there is a job

opening, who is more to be trusted, a person who comes in off the street — even

if he has good credentials — or the relative of a long-term, reliable employee?

Many Latin Americans would choose the latter on the assumption that the older

worker will make sure the new worker, her relative, measures up to the

standards of the company. Often this assumption is born out, because of the

strength of reciprocal responsibilities within the extended family. Therefore,

this study will devote considerable attention to the formation of the extended

family structure in Latin America.

The Elite Family

Family structure among elites has been called patriarchal,

meaning dominated by a

patriarch,

the man of the household and official

holder/manager of the family property. This patriarch, whose income in colonial

Latin America was generally based on a hacienda, plantation, or mine,

established the social position of the family. His effectiveness in controlling

his dependents — meaning his children, whether born of his wife or of another

woman; the women of his household (i.e. wife, sisters, sisters-in-law, mother,

mother-in-law, and possibly granddaughters); poor relatives; and domestic servants,

slaves, or tributary Indians — was a matter of utmost importance since his

reputation as an

hombre de bien

(honorable member of the community) was

at stake. Frequently, the eldest son of the patriarch succeeded him in that

position, to reap the rewards and shoulder the responsibilities implied by this

position of chief executive officer of the family.

Non-elite Families

For families lower on the social scale, the family might

not be organized around the man of the house. Indeed, in the lower ranks of

society, the family could often be said to be matriarchal, led by a widow,

single mother, or eldest sister. This did not, however, diminish the strength

of family ties and may even have fostered greater reliance on the extended

family as a source of the necessary contacts that would lead to work, a home,

or a partner.

OUTLINE OF THE BOOK

What follows will show how colonial institutions structured

daily life and were in turn structured by people’s daily lives over 200 years

of Latin American history. The discussion is divided into chapters on marriage

and home life; sexual mores and affective life; childhood and education; the

material aspects of daily existence; work and economic relationships; popular

art, entertainment, and religious life; and political systems and resistance to

them. The conclusion will summarize the key features of colonial life since

1600 after briefly sketching the achievement of independence in most of Latin

America early in the 19th century. Perhaps not surprisingly, despite this

achievement the colonial period came to its official end without bringing much

change to the daily lives of the majority of Latin Americans.

TIMELINE

1492 | Mexica-dominated Reign of Tupa Death of Sonni Catholic Sugar production Isabella of Spanish Catholic First |

1500 | Pedro Alvares |

1502 | Earliest |

1503 | Earliest |

1505 | Laws of Toro |

1512 | Laws of Burgos |

1518 | Spanish crown |

1521 | Earliest On a second |

1524 | Franciscan order |

1532 | Forces led by |

1542 | Charles I of |

1545–1563 | Council of Trent |

1549 | Portugal |

1550 | Debate at |

1569–1571 | Holy Office of |

1573 | Arrival at Potosí |

1575 | Portuguese |

1580–1640 | Portugal ruled by |

1595–1640 | Portuguese |

ca. 1618 | Town of San |

ca. 1630 | Repartimiento |

1630–1654 | The Dutch rule |

1631 | Free militiamen |

ca. 1640 | Sharp decline in |

1679 | African-born nun |

1692 | Major riot in |

1693 | Bandeirantes from |

1694 | Quilombo of |

ca. 1740 | Mexican city of |

ca. 1750 | Era of the |

1780–1783 | Massive |

1781 | Comunero revolt |

1786 | New regulations |

1789 | Nearly 2,000 |

1791–1804 | Haitian |

1794 | Mexican theater |

1795 | Short-lived |

1798 | Tailors’ |

1808–1825 | Independence era |