Damn His Blood (13 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

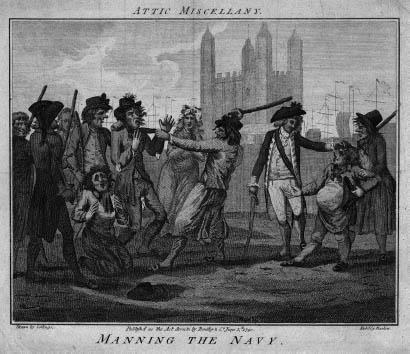

Press gangs were a familiar evil in Georgian England. In the late 1770s new legislation opened inland areas as well as coastal towns up to forced recruitment

This was an important position. The army depended on recruiting sergeants to fill its ranks quickly and efficiently in an age before conscription. Such men were typically determined, ruthless and loyal, capable of seducing, pressuring or bribing men into service and always mindful of the financial rewards available for doing a good job. Traditionally recruits came from two channels: volunteers, who were rewarded with a bounty, and pardoned criminals, who used the army as a way of escaping their past transgressions. But by 1778 it had become plain that this system was not yielding sufficient numbers and measures were rushed through Parliament to rectify the problem. By the next year the bounty for volunteers had been increased to £3 3s. a head and, of greater importance, the forced recruitment or ‘impressment’ of ‘able-bodied, idle and disorderly men who were without trade and employment’ was legalised. The British army needed soldiers, and the government was willing to give men like Samuel Evans the powers to get them.

Roving press gangs, led by recruiting sergeants and consisting of little bands of soldiers, sprang up in response to the act and they struck terror into the British population. Press gangs were nothing new; they had stalked port towns for years scouring the docks and nearby inns for out-of-work sailors and other seamen who would suit the navy. Such gangs, however, had usually remained in coastal areas, only straying inland occasionally. But by the spring of 1779 the whole of Britain was in effect opened up to forced recruitment and the following months saw a surge of new recruits, with men like Evans able to earn as much as £1 a day. The financial rewards meant that compassion was rarely extended towards loiterers, beggars or the unemployed. Arriving in a town, a press gang would usually establish its headquarters in an alehouse – known colloquially as a rondy – where they slouched away their spare time drinking, plotting and roaming the nearby streets. One source describes a gang as ‘a roistering drinking crew … never averse from a row’. Typically they were armed with cutlasses, clubs or daggers which they would use without care. One illustration of a press gang at work, depicts five expressionless soldiers dressed in tunics and cocked hats, armed with swords, pistols and truncheons, forcing men into shackles and dragging them away.

Samuel Evans was an active presence throughout the worst months of the recruiting crisis, thriving in this brutish, pragmatic world, where he was judged by his results not his methods. The job, by its nature, was opportunistic and occasionally violent. Street fights and alley scuffles with drunks, robbers and street hucksters were common. Recruiting sergeants were forced to prise information from wily informants and catch out determined men, who would go as far as incapacitating themselves (cutting off their thumbs and forefingers was the most common method) to avoid being ensnared. But it was an environment in which Samuel Evans excelled.

Evans’ success was enough to catch the attention of his superiors. A set of stiff entry requirements usually prevented those from the lower orders being appointed officers in the eighteenth century (a candidate for a commission had to hold an annual income of at least £200 – the income of a gentleman – if their commission was not bought, and most of them were), but with resources so stretched and Evans so obviously able, the usual barriers were temporarily relaxed, and on Saturday 30 October the

London Gazette

6

carried the news that Samuel Evans had been appointed an officer. He had joined the ranks of the gentry and was thrust into a team of regimental officers comprising two majors, seven captains, eleven lieutenants, eight ensigns, a chaplain, an adjutant, a quartermaster and a surgeon at the head of a body of many hundreds of men. It was the single most significant day of Samuel Evans’ life and it left him more powerful than ever.

By October 1779 Evans’ regiment was ready for duty, and in December it set sail from Portsmouth for the West Indies. The 89th Foot had originally been bound for Jamaica, but it was diverted to the Leeward Islands, where it saw action in Saint Lucia. Afterwards the regiment was stationed in Barbados and Tobago, but as time passed its men were increasingly worn down by what was already known as the ‘torrid zone’.

7

This label applied to much of the Caribbean and referred to the ruthless mix of New and Old World diseases that thrived in the humid atmosphere and tore through the constitution of any unadjusted arrival. Yellow fever, which inflicted a sufferer with black vomit, a black tongue and yellow skin, was the most prevalent among the maladies to strike the 89th Foot, but hordes of other diseases thrived with almost equal force, infecting men with high fevers, shivering fits, sores, weeping wounds and other conditions for which there was no known cure. Ten out of the 29 officers fell victim to tropical disease during the tour of the Caribbean, a total which left the regiment desperately short of leaders and precipitated the promotion of Ensign Evans to lieutenant in May 1780.

A year later the 89th Foot was relieved, and it set sail for England on 4 May 1781. Thereafter it spent the summer recruiting afresh, at Hereford, Dudley, Leominster and Ludlow, but by this point the war was drawing to a close and the government’s thirst for men was satisfied. Shortly before the Peace of Versailles was signed in February 1783 the government circulated a memorandum stating that ‘all men enlisted since 16 December 1775 shall be discharged when peace declared, provided they have served three years’. It was another fortuitous turn of events for Evans, who in May 1782 had received his final promotion – to captain – and in March 1783 he began his long half-pay retirement.

By now he was styling himself as Captain Evans, an evocative identity rich in patriotic overtones which allowed him to transfer an element of military glamour and hierarchy into his civilian life. At the age of 50 he was a gentleman, admired, connected and possibly notorious around Worcestershire. His life had followed an upward trajectory for many years, and by the early 1780s all the trappings of his early days as a commoner seemed rubbed away, leaving the man Mary Sherwood would later encounter. ‘Whatever his parentage

8

might have been,’ she explained, ‘he had an air of a gentleman of the old school, and not in the least of a person suddenly raised from a low estate. He was, when it pleased him, equally polite and courteous in his manners, as well as dignified in his general carriage.’ Such a radical transformation as Sherwood suggests, was not easily undertaken, and it exposes Evans both as an ambitious man keen to shake off his past but also able, almost chameleon-like, to adapt to different environments. Two decades later, in Oddingley, he retained his military aura and for many of the parishioners he would have been a towering personality, to be feared and respected in equal measure. In an age when very few travelled beyond the neighbouring counties or as far as London, Evans would have been considered an adventurer, a self-made man of the same generation as James Cook, the son of a Yorkshire day labourer who had entered the navy as an able seaman and risen to the rank of captain.

By experience and nature Evans was a leader. The social boundaries that had stood before him at the opening of his career had been overcome, and there would have been little to suggest that Parker and his demands for the tithe were anything more than another stone to be kicked from his path. Like many others who return from battlefields and are thrown back into society, Evans had a dangerous self-confidence burning inside him. In his dealings with Parker and Perkins, this element is always just beneath the surface.

In his very first publication,

Sketches By Boz

, Charles Dickens caricatures the half-pay captain – a familiar personality in early-nineteenth-century Britain, like an unruly sage full of nuisance and tales of war and with little time for civic niceties. It’s a sharp skittish description which in some ways could be applied to Evans.

He attends every vestry meeting

9

that is held; always opposes the constituted authorities of the parish, denounces the profligacy of the church wardens, contends legal points against the vestry clerk, will make the best tax gatherer wait for his money till he won’t call any longer, and then he sends it; finds fault with the sermon every Sunday, says the organist ought to be ashamed of himself, offers to back himself for any amount to sing the psalms better than all the children put together, male and female, and, in short, conducts himself in the most turbulent and uproarious manner.

Captain Evans brought much of this same unruly dominance to Oddingley with him when he arrived at Church Farm in 1798. He demonstrated a flair for organising men, assembling support for a cause, aggressively pursuing a line of argument as well as a willingness to engage to his advantage with awkward situations. In May 1806 Oddingley was visited by the local militia, and eligible villagers who had been drawn by lots to serve were required to present themselves for inspection. George Banks was one of these and was only saved from service by the Captain, who ordered a parishioner named Clement Churchill to stand in his place. It was a clever switch, as Evans knew full well that Churchill would be rejected due to his height (the militia required men at least five feet four inches tall). All the while, Churchill recalled, the real George Banks was at plough in Oddingley.

This little vignette reveals how the Captain was ready and willing to exploit situations for his own benefit or to help out those close to him. It also demonstrates his ability to carry off a bare-faced lie with composure. Perhaps he knew the recruiting sergeants conducting the muster; he certainly knew how the process worked and how best to play it. His status as a magistrate, charged with upholding the law, seems not to have had the slightest bearing on his actions.

A less immediate but equally powerful echo of the Captain’s military days comes in the nature and tone of the farmer’s language towards Parker throughout the quarrel. The most commonly recorded of their curses was ‘damn’, a verb which has subsequently lost much of its power but at the time remained potent, bordering on the taboo. In Christian societies damning a person meant wishing them away to hell and the Devil, to a life of eternal punishment, pain and misery. For the outwardly respectable classes it was a profanity best hidden away in private, but it was used openly by the lower orders, especially soldiers and seamen, for whom it was the sharpest insult, reserved for personal enemies, dangerous social deviants and figures of hate.

To be damned publicly was ominous. Shortly before his home was razed to the ground and his effigy burnt by a baying mob in Birmingham on Bastille Day 1791 Joseph Priestley, the notorious dissenting chemist, had to endure the sight of every blank wall in the town centre being chalked with the slogan ‘Damn Priestley’

10

by loyalist mobs. In the very same year a definition of the verb was left, inadvertently, in James Boswell’s biography of Dr Johnson. Boswell included the following exchange between Johnson and a friend:

Johnson: I am afraid that I may be one of those who shall be damned (looking dismally).

Dr Adams: What do you mean by damned?

Johnson: (passionately and loudly) Sent to Hell, Sir, and punished everlastingly.

Many publishers censored the word from pamphlets, fearful that they might be aiding its spread. Its use provoked an uneasy feeling in the minds of right-minded Christians, who week after week were reminded of the horrors of hell from the pulpit. Some writers used its power to enliven their work. Byron intensified the shock of his poem

Don Juan

by embroidering one verse with the curse ‘Damn his eyes’, which he referred to as ‘that once all-famous oath’. More striking still was Jonathan Swift’s haunting poem

The Place of the Damned

, which drew its power from repetition of the word, leaving a bitter sense of anger and hopelessness: ‘Damned lawyers and judges,

11

damned lords and damned squires; Damned spies and informers, damned friends and damned liars.’

Swift’s was a technique that moderate writers shied away from, and for the century and a half which followed many authors avoided the word altogether and others sidestepped what was increasingly considered offensive by resorting to euphemisms such as ‘jiggered’ or ‘drat’, in itself a shortened version of another religious curse ‘God rot your bones’ or ‘God rot.’ In newspaper reports ‘damn’ was rare, and when it did surface it was almost universally linked to the criminal and malicious sectors of society. Dickens reserved it for exceptional moments, such as the rooftop scene at the end of

Oliver Twist

which marked Bill Sykes’ grisly end. ‘“Damn you!” cried the desperate ruffian. “Do your worst! I’ll cheat you yet!”’