Damn His Blood (16 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

By the time John Barnett refused Lench’s plea for help ten minutes had passed since the attack and any chance of an effective hue and cry had been dashed. When Perkins left for Pyndar’s house at about half past five the likelihood of a quick capture was fading with the afternoon sun.

Betty Perkins had learnt the news of the murder at the same time as her husband and at about 5.30 p.m. had set off for the glebe fields to see Parker’s body. On her way through the village she was stopped by a stranger on horseback, who asked her what had happened. This was a farmer, Mr Hemmus, from Woofferton in Shropshire. Hemmus had been to Bromsgrove Fair that day and, like many others in the lanes, was now travelling home. Betty told him that their clergyman had been attacked and murdered, and Hemmus replied that he ‘would go after the murderer if anybody would go along with him’.

James Tustin, who was standing nearby, instantly volunteered to join Hemmus ‘if anyone would lend him a horse’. Betty Perkins agreed to do so, and the party set off towards Pound Farm, where Tustin left them at the gate to change his clothes. Meanwhile Betty carried on to Oddingley Lane Farm, where she had ‘her horse got ready’ and brought back up to the gate for Tustin. Betty then continued up to the glebe, where she met Tustin’s young son. The boy told her that his father had been prevented from joining Mr Hemmus by his mistress, Mrs Barnett. Old Mrs Barnett had refused to allow Tustin to leave the farm with a criminal loose in the countryside. If it was not for Mrs Barnett, the boy explained, ‘he would have gone in a minute’. Without help, Hemmus had left Oddingley and continued on his journey home.

As frustrated in her attempts to aid the chase as Lench had been before her, Betty Perkins continued to the centre of the glebe, where many villagers were crowded in mute horror about Parker’s body. The clergyman’s groin was exposed and badly burnt, his head bloodied and battered. Surman, who by now had returned to the scene of the crime, had doused the flames and pulled off Parker’s singed breeches and underclothes, exposing the charred and shot-freckled skin below. After initially fleeing the glebe, it seems that Surman had spent some time at Pound Farm during the preceding 20 minutes. She too had witnessed the Barnetts’ attempts to disrupt the manhunt. ‘Four or five others offered to go with Mr Barnett’s servant [Tustin],’ she later remembered. ‘But Mr John Barnett would not let him go.’

Thomas Giles now reappeared with the news that the murderer had threatened him and had run off toward Hindlip, a neighbouring parish. Giles then rooted in the hedgerow in search of the weapon that he had seen half an hour before. Soon he drew out an old muzzle-loading shotgun. The stock of the weapon was broken in two at the lock. After shooting the clergyman, the murderer had delivered a series – perhaps two or three – of awful injuries to Parker’s head with the stock of the weapon. It was a wild and merciless crime. The executioner would have stared down into his victim’s eyes as he delivered the fatal blows. As if setting the scraps of evidence down in a hateful collage, Giles laid the broken, bent shotgun down beside Parker’s corpse. Tustin picked up the gun bag and placed it over the clergyman’s exposed groin.

At six o’clock Reverend Pyndar arrived in the glebe meadow to assume control of the investigation. With no police force people relied upon the scattered network of unpaid magistrates to marshal their communities and to act in emergencies. As a justice of the peace, ‘the workhorse of everyday magistrate power’,

7

Pyndar held an ancient feudal title laced with imagery and prestige. A vast proportion of the JPs in England were well-to-do parsons and country squires (to be eligible an individual had to have an income in excess of £100 a year) like Pyndar. They were considered well suited to the role, which further raised their status and strengthened their influence over a community. Ever since the fourteenth century magistrates had been responsible for hearing minor offences, and they had the power to have petty offenders whipped or thrown into houses of correction and more serious criminals committed to gaol to await trial at the assize – or criminal – courts.

Pyndar looked down at Parker’s corpse. He picked up the bag and asked Perkins what he thought. Perkins replied that he ‘thought it came from Droitwich as it smelt salty’. Pyndar then ordered Parker’s body to be removed to the rectory. But rather than carrying the corpse, a decision was made to send for a chair from the rectory on which the body could be transported more suitably. Several minutes later a pathetic cortège embarked for Church Lane. The corpse – slumped back in the chair – was carried by Tustin and some other farmhands towards the rectory as if it was the centrepiece of a bizarre religious procession. A train of parishioners, passers-by, children and curious onlookers walked behind.

What followed in the minutes afterwards would be disputed in the village for years to come. Susan Surman claimed that Pyndar, shocked at John Barnett’s apathy, determined to seek him out for an explanation. Surman had told Pyndar that her master could be found at his farmhouse, but when he knocked at the door Old Mrs Barnett told him her son was out – ‘that he had gone to the Captain’s’. Pyndar then wheeled around to confront Surman, whom he accused of ‘telling him a tale’. The dairymaid – in a dangerous breach of loyalty – protested, ‘I have not at all, for Mr John Barnett is in the parlour [and] had just before stuck his head out of the window and told James Tustin to go to the stable [and her] to mind her milking.’

At this Pyndar returned to Pound Farm, forcing entry to the farmhouse and dragging Barnett out into the yard. According to Surman, it was a dramatic scene. It was now early evening and knots of villagers were gathered outside Pound Farm watching the action unravel. They saw Pyndar interrogate Barnett, and as he did so the bearers of the chair carrying Parker’s helpless corpse edged into view behind them. In full sight of the villagers Pyndar pressed Barnett asking ‘if he knew anything of

that

job’. Barnett replied that he did not, and protested that he was ‘very sorry that it had happened’.

There is something improbable in Surman’s story. She seems to suggest that Tustin was at Pound Farm when several other sources have him transporting Parker’s body to the rectory. More importantly, nobody who was present would ever corroborate her account of Pyndar fetching Barnett out of the parlour. There were, though, various reports of a confrontation between the magistrate and the farmer. John Perkins claimed that Pyndar met Barnett further along Church Lane as if, he reasoned, Barnett was returning from Captain Evans’. Perkins heard Pyndar call to the farmer, ‘Barnett, you have had a very pretty job happen in your parish, are you not ashamed of it? When those two butchers came to your house to go in search of the murderer you refused to go?’

Barnett said nothing. The magistrate – seemingly overcome with fury or frustration: a friend and peer murdered, the suspect escaped and one of the parish’s leading men apparently indifferent – then raged at the farmer. He shouted, ‘You rascal! You villain! If you had a dog and had any love for him you would have saved him if you could! – I shall think of you as long as I live.’ John Barnett dropped his head and ‘never said a word’.

Parker’s corpse arrived at the rectory at about 7 p.m., around two hours after he had set off up Church Lane for his cows. Gone in those few hours were the tranquillity of a summer afternoon and the fragile peace of the village, which so often in recent months and years had been threatened. The noises of labourers at work – the rattle of their handcarts, the swinging of scythes and the scrape of rakes – were replaced by the sound of horses’ hooves as George Day, the Parkers’ servant boy, left the rectory garden on Perkins’ old nag for Worcester.

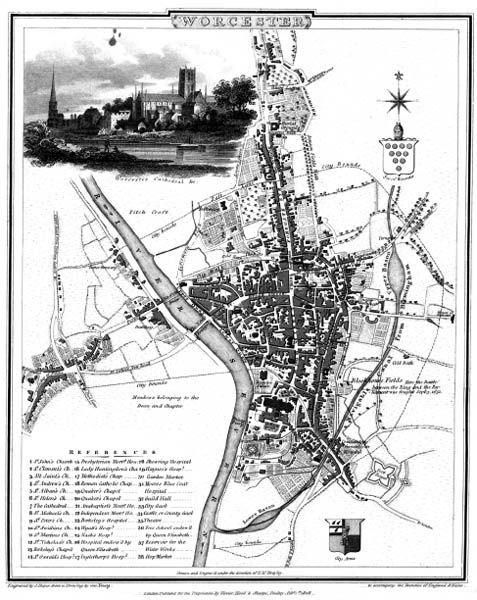

Worcester in the early nineteenth century, printed by Roper & Cole, 1808

That all minds should now turn towards Worcester was logical. It was a fine city, built almost entirely of red brick with the exception of a handful of public buildings, its churches and exquisite medieval cathedral. Although its streets were capacious, newly paved and lighted, the city, with a population of 12,792, offered two sources of hope for the fleeing murderer. First, it would allow him to plunge into the crowds, where he might have friends or accomplices lying in wait. Second, it would give him access to a great number of routes of further escape. Worcester sat almost at the heart of England and was served by a rapidly developing network of turnpike roads heading off in all directions: towards Tewkesbury to the south, to Birmingham in the north and Evesham in the south-east. The city was popular with travellers and tradesmen, who came to view, purchase or collect orders of its famous porcelain or gloves, and at all hours of the day wagons, mail and stage coaches rolled sluggishly out of the yards of its major public houses into Foregate Street, Broad Street and the High Street. In his

Brief History of Worcester

8

(1806) J. Tymbs noted that Worcester ‘is generally allowed by most travellers not to have an equal’.

1

If the murderer could reach the city before the news of his crime, then he could easily secure passage onwards.

Worcester lay just six miles from Oddingley, but for a traveller on the winding lanes or wading through the long summer grass it was not a simple distance to cover. Without risking the turnpike – known locally as the Droitwich Road – there was little chance of him reaching Worcester in less than two hours. The Birmingham Light Coach had already left earlier that afternoon, and the next best opportunities to escape the county were the Bristol Mail, which occasionally took passengers and departed from the Star and Garter public house in Foregate Street at 8.30 p.m., and the London Stage Coach, which left Angel Street in the city centre at 10 p.m. each Tuesday. That coach, perhaps, was the most logical. It would arrive three days later at the Bull and Mouth coaching inn in the City of London.

The primary aim of George Day’s gallop to the city that evening was to close these routes of escape. Then he would deliver Thomas Giles and John Lench’s description of the wanted man to the authorities. In contrast to the lightly policed community at Oddingley, Worcester was tightly governed. It had five aldermen – senior members of the local corporation – who also served as justices of the peace, a sheriff, thirteen constables and four beadles. The centre of Worcester was about forty minutes’ ride away at the gallop. If the murderer intended to take either the London or the Bristol coaches that night, there was still enough time to catch him.

fn1

Undergarments worn traditionally by clergymen.

CHAPTER 7

Dead and Gone

Church Farm, Oddingley, Evening, 24 June 1806

ODDINGLEY’S LANES WERE far busier than usual on Midsummer evening. They were not only filled with the villagers who gathered at the top of Church Lane and beside the rectory gate, where they awaited orders from Pyndar or a dramatic appearance of the captured murderer, but with farmers, traders and artisans riding or walking home from Bromsgrove Fair. Among the travellers were Thomas Green,

1

a tailor from Upton Snodsbury, a nearby village, and his son William. According to Green’s later account, they had met John Perkins just north of Oddingley, near Newland Common at between half past five and six o’clock. Green was acquainted with several of the villagers, and Perkins told him that Parker had been shot. At this, Green and his son turned their horses towards the glebe, where they saw Parker’s body lying where it had fallen. Shortly after, they formed part of the macabre procession to the rectory. Green recalled that he had ‘staid [

sic

] some time’ in the village before deciding, at between seven and eight o’clock, to visit Captain Evans at Church Farm.

Nothing had been heard of Captain Evans in the hours that immediately followed Parker’s murder. He had not joined Thomas Clewes, Hardcourt, Marshall and William Barnett at Bromsgrove Fair, so it was natural for Green to suppose he might be found at Church Farm. It was just a few minutes’ ride down Church Lane, which twisted sharply left around the borders of a pear orchard, from the rectory to the Captain’s home. Green fastened his horse to the fold-yard gate and knocked at the farmhouse door. The tailor must have been well known to the household as he was instantly invited in by one of the servants. Green entered the parlour. There he saw Captain Evans and John Barnett sat at the table. ‘They were drinking something out of a black bottle.’

Thomas Green, imagining the two men knew nothing of what had happened, told them of the murder, to which ‘both seemed surprised as if they had never heard of it before’. The Captain, by way of an explanation, took up a scrap of paper from the table, telling Green that they had just been settling the income tax together. Barnett remained as silent as he had been for much of the past two hours.