Damn His Blood (19 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

Worcester had already been pinpointed as Heming’s most likely destination, but Pyndar had been wise not to limit his attentions. Just seven miles to the northeast of the county city and little more than two miles from Oddingley was Droitwich. Heming could easily have doubled back and risked the trip homeward, which he would have been able to complete, at a pace, in little more than an hour.

And for Pyndar there were already hints that whatever had taken place in Oddingley that afternoon had its roots in Droitwich. Not only did Heming live there but he had been seen with Clewes in the Red Lion’s taproom, damning Reverend Parker just weeks before. Surely such an indiscretion would only occur in an environment where the men felt comfortable? A second reason to draw suspicion towards Droitwich was that the gun bag had smelled of salt.

Salt defined Droitwich. In his history of Worcestershire T. C. Tuberville observed, ‘Salt manufacture at Droitwich

1

is one of the most ancient businesses in the kingdom,’ and the industry had left its scars on the landscape: the sheds, workshops and tall smouldering chimneys of the salt works, served by a steady stream of carts clattering to and fro between the pits (wiches) and packhorses lumbering off to distant traders and their markets.

The market town itself was inconspicuous, set in a valley through which the gentle River Salwarp flowed. To the untrained eye there was little to set it apart from any other place of its sort, but 173 feet beneath the marl-capped surface of the valley floor a subterranean stream – just 22 inches deep – passed over a sheet of rock salt, transforming the water into strong brine. ‘The brine from all the pits is perfectly limpid,’ reported a paper for the

Philosophical Magazine

in 1812, ‘… and when in a large body

2

had a pale greenish hue similar to that of sea water. To the taste it is intensely saline, but without any degree of bitterness.’

The process for converting this brine into Droitwich salt was curious. The weekly Victorian magazine

Household Words

explained the method to its readers in a lucid and colourful article in the 1850s.

Brine boiling and salt making

3

is hot, steaming work. Go into any of the works [at Droitwich] and you will see men naked to the waist, employed in an atmosphere only just bearable by strangers. You will see that the brine is pumped up from the pits into reservoirs; you will see ranges of large shallow quadrangular iron pans, placed over firecely heated furnaces; you will see the brine flow into the pans, and in due time bubble and boil and evaporate with great rapidity: you see that the salt evidently separates by degrees from the water and granulates at the bottom of the pan; you see men ladle up this granulated salt with flattish shovels and transfer it to draining vessels; and you finally see it put into oblong boxes, whence it is to be carried to the store room to be dried.

By the time this article was written Droitwich was producing around 60,000 tons of salt each year. This was a much smaller amount than came from Cheshire, where miners dug out salt with ‘the pick, the shovel, the blast and the forge’, but evaporation was a far more economical process. The effect of the industry on the neighbourhood was profound. It not only resulted in the ‘saltways’, which fanned out across the country, but also necessitated the building of Droitwich Canal

4

– a masterpiece of enlightened engineering by James Brindley – for the enormous sum of £23,500 between 1767 and 1771. Furthermore, it was one of the chief factors in the near-total destruction of Feckenham Forest, with Hugh Miller, the Scottish geologist and writer, claiming that ‘six thousand loads of young pole wood,

5

easily cloven’ were required to fuel the furnaces each year.

Long before 1806 the trees in Oddingley parish would have been among the first parts of Feckenham Forest lost to the salt works. Logging had continued until the completion of Droitwich Canal made coal a more efficient source of energy. Traffic along the saltways had also thinned, as packhorses had been replaced with barges. Nevertheless, at the beginning of the nineteenth century Droitwich’s streets and the surrounding lanes were still a ferment of business and enterprise.

Household Words

contrasted the town with the more upmarket Malvern. It observed, ‘If Worcester has a fashionable neighbour

6

on the one side, Malvern, it has a sober industrious neighbour on the other, Droitwich. The one spends money; the other makes money. Worcester acts as a metropolis for both.’

To Hugh Miller, who arrived on a bleak autumnal day, Droitwich appeared a dull dispiriting place. The fields on either side of the valley had a ‘dank blackened look’ and the town’s roads and streets ‘were dark with mud’. He continued:

Most of the houses wore the dingy tints of a remote and somewhat neglected antiquity. Droitwich was altogether, as I saw it, a sombre looking place, with its grey old church looking down upon it from a scraggy wood covered hill; and what struck me as peculiarly picturesque was, that from this dark centre there should be passing continually outwards, by road or canal, waggons, carts, track-boats, barges all laden with pure white salt, that looked in their piled up heaps like wreaths of drifted snow. There could not be two things more unlike than the great staple of the town and the town itself. There hung too, over the blackened roofs, a white volume of vapour – the steam of numerous salt pans driven off in the course of evaporation by the heat – which also strikingly contrasted with the general blackness.

Droitwich was a prosperous place – the salt works yielded an enormous annual sum of £250,000. Such a steady flow of money meant it was more than a mere market town; it was also a destination for traders and a hive for the financially ambitious. For Oddingley it was a centre of trade, a place to meet friends, strike deals, purchase farming tools or seek new services. Most weeks farmers like Thomas Clewes and John Barnett would travel to the town for its Friday Market, stopping for a drink in the Barley Mow, the Black Boy or the Red Lion.

The town had also played a vital role in Captain Evans’ life. In March 1783, when he retired from the 89th Foot, he had swapped a successful military career for an uncertain civilian future. Then aged about 50, Evans entered his retirement in strong financial shape. Several years of officer’s pay would have been bolstered by any spoils he might have secured during the recruitment crisis or on his Atlantic tour, where captured enemy property and money would have been divided among the soldiers. But although he had money, Captain Evans decided against establishing his own household. Instead he took a room with the Banks family in Whitton, a village three miles from Ludlow. Why he preferred to do this is uncertain. His regiment had been stationed in the area the previous year, and Evans, being billeted with them and enjoying their company, might have simply decided to stay. Perhaps he enjoyed living in a traditional family unit, unaccustomed as he was to life outside his regiment. There is no sign that the Captain had any blood relations of his own.

The Banks family was headed by Mary and her husband William. They had a family of seven children, five daughters and two sons. The eldest son, George Banks, the future bailiff of Church Farm, was baptised in Whitton in 1782. This date coincides with Evans’ retirement from the 89th Foot and when he first met the family. The later rumours that suggest he was George’s natural father are questionable given William Banks was still alive at this point. It is clear, however, that whatever connection there was between Evans and George Banks stretched right back to his very beginning.

A certain mystery surrounds the Captain’s movements over the next decade. It is evident, however, that throughout these years both his social status and financial means continued to improve. When he reappears in records in the mid-1790s it is as an older but more successful gentleman, financially secure and more powerful than ever. He may well have remained with the Banks family throughout these years, but it is clear that his attention had returned to his native Worcestershire. The town clerk of Droitwich made an entry in his books in 1794 marking Evans’ formal return to county life: ‘At a Chamber Meeting

7

held for the Borough of Droitwich, on the 6th October, 1794, Samuel Evans, late of Kidderminster and now of the Parish of Burford in the County of Salop, Captain in His Majesty’s late 89th Regiment of Foot, was elected and made a Free Burgess of the said Borough.’ A second record was added, almost precisely a year later: ‘At a Chamber Meeting held the 5th of October 1795, Samuel Evans was elected and chosen one of the Bailiffs of the said Borough.’

The mid-1790s were years of conflict. Since 1793 Britain had been at war with the revolutionary government in France and Evans may have owed his new appointments to a growing sense of fear, as Britons strove to sublimate their anxieties by promoting experienced and decisive men to positions of authority. For Evans it was a personal triumph. He was now a burgess and a bailiff, part of the local magistracy, achievements to match and surpass any in his previous life.

Evans filled one of the two magisterial roles elected each year by the Droitwich Corporation. It was a powerful, prestigious and testing position, especially at such a time of civil unrest. To even be considered for the post, the Captain would have had to possess certain social and material qualities. As the historian Clive Emsley explains, ‘He [the magistrate] had to be a man

8

of some wealth and social standing to have his name entered on a county’s commission of the peace in the first place; he then had to be of sufficient public spirit to take out his dedimus potestatem, which involved travelling to the county town, swearing an oath before the clerk of the peace, and paying the appropriate fees.’

As a magistrate the Captain was called on to impose summary justice in a wide range of cases, including felonies such as common assault, petty larceny and robbery, and other minor crimes such as selling unlicensed goods. Several records of the Captain’s service have survived. On 3 October 1797 he took the testimony of a Richard Barber, who claimed to have been violently beaten by two men, Thomas Tagg and Joseph Taylor. Barber was a watchmaker, Tagg a cabinetmaker and Taylor a farrier, a specialist horseman. Perhaps it was no more than a drunken scuffle, or perhaps it was reflective of the resentment that festered in small towns between competing tradesmen. More significantly, though, the deposition is the first recorded mention of Joseph Taylor.

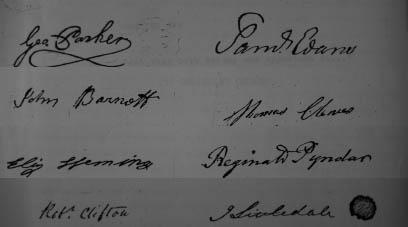

With physical images of almost all the key characters lost, these signatures stand in their place

Two more records relating to Evans date from the following year. On 3 September 1798 he received an instruction to advance 30 weeks’ pay to a Droitwich lady whose husband had been drafted into the Worcester Militia. Later that same month he took the deposition of a Miss Harrison who stated that she had been assaulted by two women. Harrison was illiterate and signed her evidence with a clumsy lopsided cross. Evans’ signature also appears on all of the forms. As one of the few direct links we have with him, his writing is revealing. The S of Samuel is looped and florid, slanted at an almost jaunty angle slightly towards the right. The E of Evans is similarly formed. In both there are traces of a careless, slightly hurried hand, but if it is the hand of a pragmatist, it is also the hand of a student: someone who has studied a style without quite being able to effect it.

Such incidents were typical of a magistrate’s workload, and Evans would have dealt with many similar cases. A further duty, and a far more prestigious one, involved overseeing elections in the borough. One of the earliest records of Captain Evans’ service relates to the 1796 general election. The document states that the following ‘oath was administered to Jacob Turner and Samuel Evans Esqs, bailiffs of the Borough of Droitwich on the 27th day of May 1796’:

I do solemnly swear that I have not directly nor indirectly received any sum or sums of money, office, place or employment, gratuity or reward or any bond, bill, note or any promise of gratuity whatsoever either myself or any other person to my use or benefit or advantage for making my return at the present election, and that I will return which person or persons as shall to the best of my judgement appear to me to have the majority of legal votes.

This oath was read before a variety of local dignitaries, including Edward Foley, the former Droitwich MP and the current member for Worcestershire. It gives a rare glimpse of the Captain’s connection with these men. In line with the exclusive electoral system of the time, Evans was also one of just 14 voters who returned two members to Parliament to represent the town nationally. It was an uncommon privilege and another mark of his exceptional local importance. He now had property; he most probably held shares in the salt springs; he was connected – in different ways – to the highest and lowest classes of Droitwich society. It is easy to see how he secured the deeds to Church Farm from Foley in 1798, when the property fell vacant. Here was a fine old manor house in a quiet nearby parish. Church Farm was to become the Captain’s country residence, the final missing piece in a life built from nothing.