Dancing in the Darkness (12 page)

Read Dancing in the Darkness Online

Authors: Frankie Poullain

H

ouses brick up the imagination and emotions are a waste of time – unless you have kids, of course, in which case both come in handy. Now cut adrift from my livelihood and without a pot to piss in – at least until Justin and my lawyers could reach an amicable settlement – I retired to the only place I could legitimately call home: a 500-year-old rundown castle in a twilight zone of rural France inhabited by inbred locals and dodgy ex-pat builders: ‘Le Vieux Château’.

According to a press statement put out by The Darkness, I had left the band to concentrate on fishing and growing vegetables in the grounds of this manor, in the Charentes region of France, but in truth the lake was full of pesticides from my neighbouring farmer’s fields, and I never got round to buying a hosepipe long enough to reach my veggie patch, leaving them to wither on the vine. It was imperative, then, to turn these two negatives into a positive.

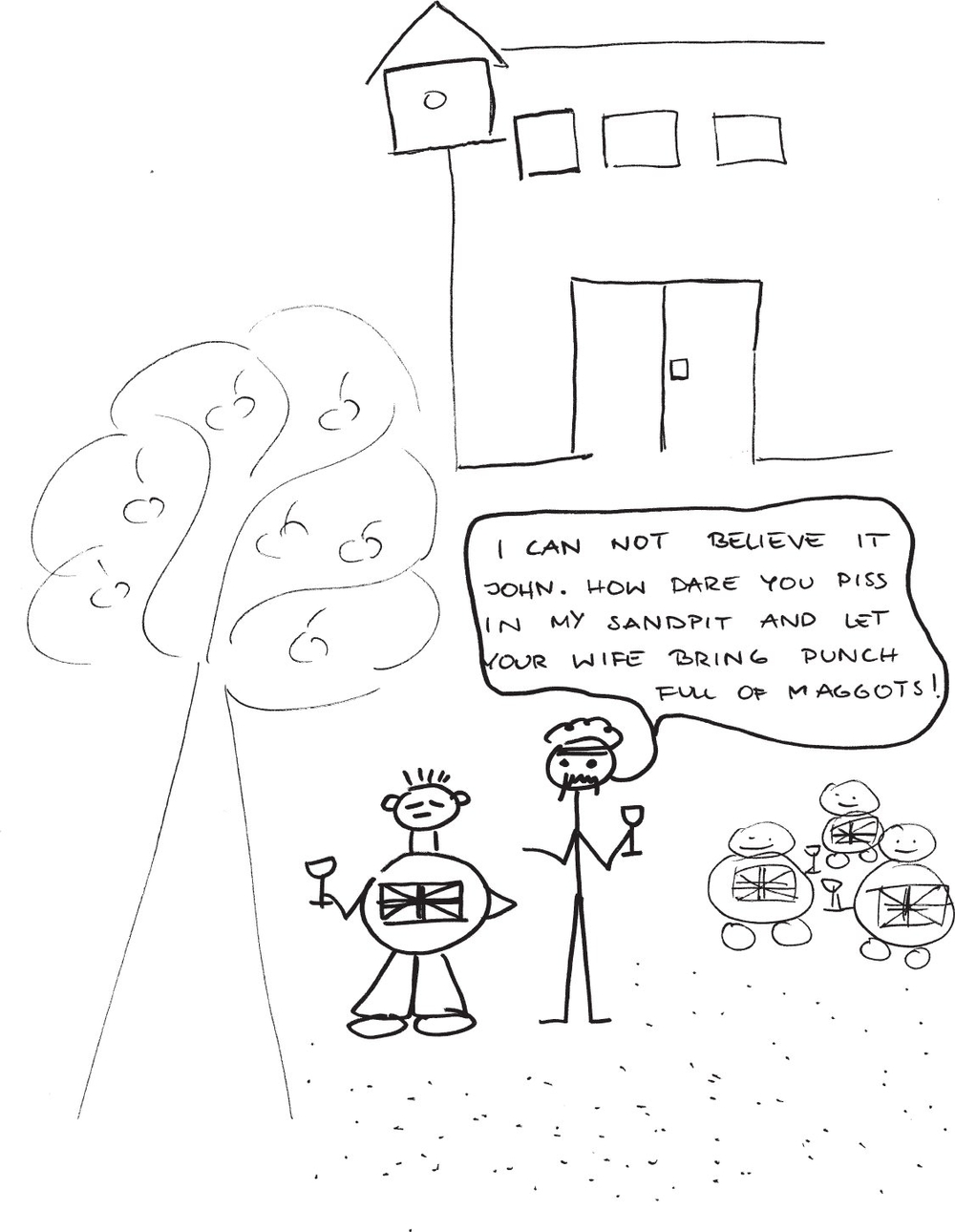

I decided on a vast sand pit, so I could enjoy beach volleyball in the afternoon sun with my neighbours – it sounds so innocuous when I write it down now, but, looking back, I can see that I became unnaturally fixated on the idea. My guests in residence – artist Jonathan Gent and his partner-cum-muse Natalie Topp – sat patiently as I buzzed around them, shovel in hand, a whirlwind of righteous energy. It wasn’t easy preparing the pit, laying tarpaulin and flattening sand under a baking-hot sun.

It’s said that heat can do strange things to people. That would explain why Jonny and I failed to take into account an enormous overhanging apple tree. Soon, a plague of festering apples littered the sand and being delicate aesthetes we never did get round to clearing them, or even erecting a net. There wasn’t much point – not now that we’d created the world’s largest maggot adventure park. When my three recently acquired kittens, sensing a once-

in-a

-lifetime opportunity, commandeered it as a

king-sized

litter tray, the stench became truly unbearable and my spirits sank to an all-time low. I realised that beach volleyball was not to be. Jonny and Natalie

duly departed and I was left to fend for myself in this cursed abode.

One night, I decided to try a curry from the

ex-pat

Indian restaurant in nearby Chasseneuil. The dusk drew in as I weaved my car homewards through the country lanes, to avoid any unwanted gendarme attention (I had no licence or insurance), curry on the floor next to me. I hoped the containers wouldn’t leak. The last thing I needed was molten jalfrezi on my bespoke Merc interior – that garlic-and-almond naan would be put to better use than mopping up wasted sauce. Bearing in mind this turmoil, I leaned down to avert a potential mishap. The next thing I remember was being

nose-deep

in poppadum fragments and mango chutney chunks – I’d veered right into a five-foot ditch by the side of the road. Luckily, a burly lorry driver came to my assistance before the police arrived. He pulled me out of the trench and I headed homewards with my daal between my legs

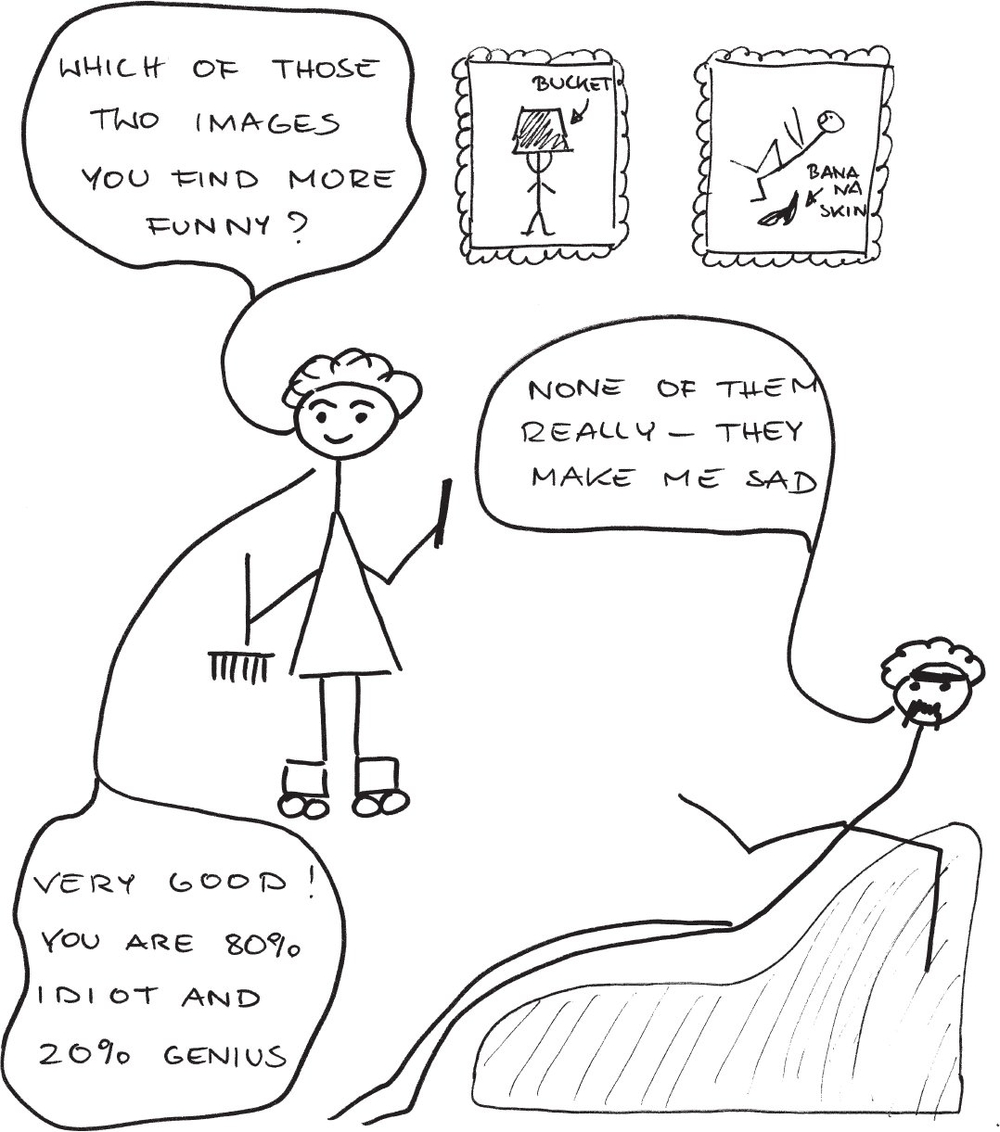

At my lowest ebb, I began to receive visits from a roller-skating 26-year-old house cleaner with a shock of curly hair. Ania was Polish and, on first impressions, quite an oddball. That said, she definitely saved me from drowning in my own thoughts, because her style of cleaning was very noisy and messy. But

gradually the chateau regained some of its former splendour and my bad thoughts began to dust themselves off. Then, when she felt more confident, I’d be subjected to a session of rapid-fire questions – annoyingly tactless at first but ultimately enlightening.

One day, I chanced upon a thick pile of her sketches and notes. I studied them with interest, not least because the drawings were based around my life before, during and after The Darkness. This took me by surprise, because I’d thought all those questions were purely for her own amusement.

The more I studied these drawings, with their philosophical tag lines, the more I could see a clear narrative emerge, with a different point of view on the events in my life. Perhaps everything really did happen for a reason after all. The two of us set about outlining a philosophy that would serve as the basis of a guidebook to help others like me.

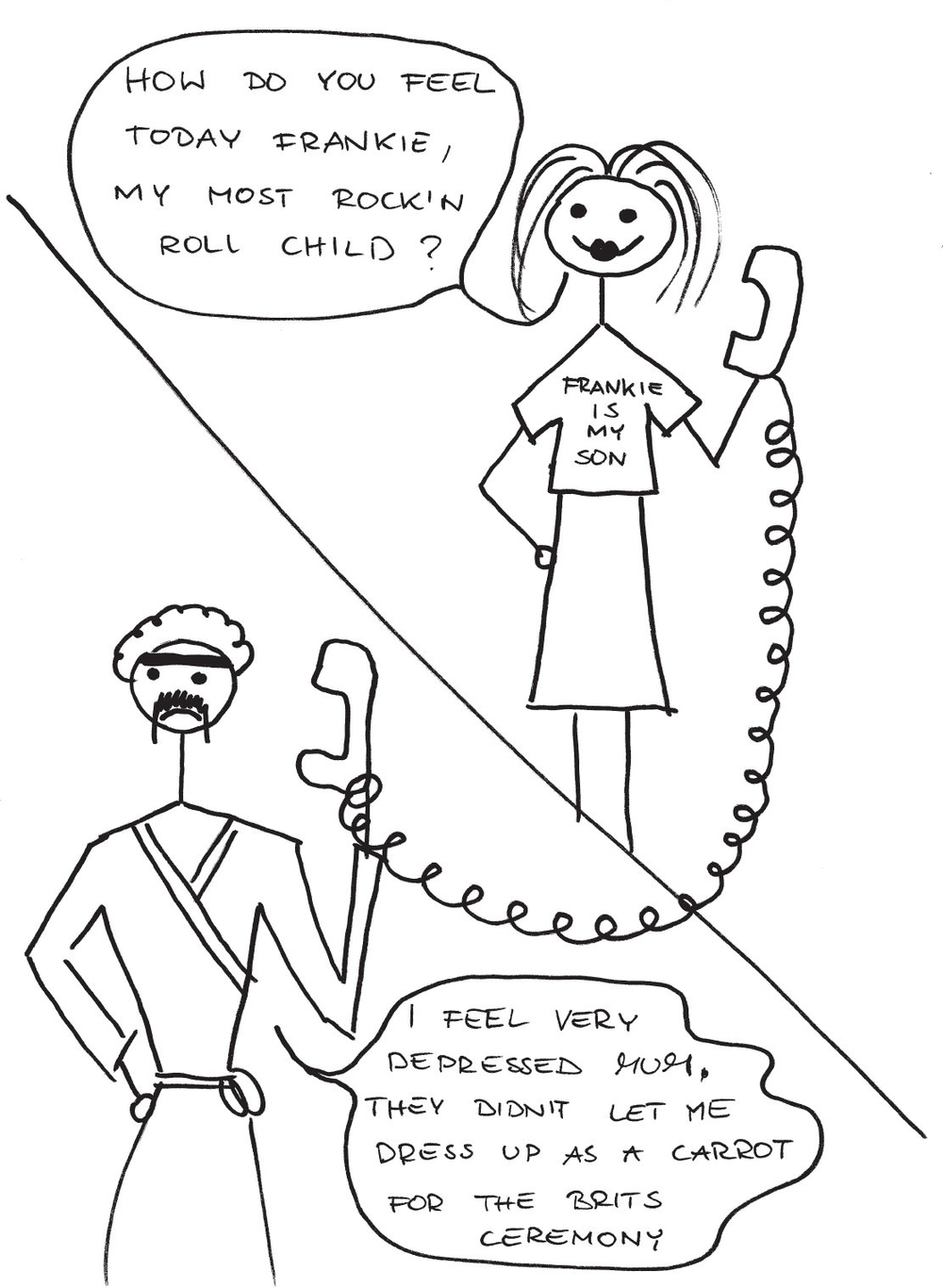

But before I could help other curly-brained creatures, I had to help myself. At least, that’s the conclusion I arrived at initially. On the other hand, hadn’t my own mother drummed it into me that I could only find happiness through helping others? So what order was I supposed to do it in? I could carry on ‘chicken-and-egg-ing’ for the rest of my life if I didn’t make a decision fast.

‘T

o create a philosophy based on your

own

behaviour, you should first write a book on your formative experiences, then analyse your actions and thinking processes. Eventually you will pinpoint trends and rules of behaviour and the philosophy will come like enlightenment came to Buddha and Mohammed.’ Those were the words of my Polish cleaner when I tried to show off to her about how many books I’d read.

There is philosophy behind every man, so here are my very own eight steps to ‘Dancing in the Darkness’:

1 Celebrate your mistakes and mourn your achievements.

2 Excel at doing what you’re not good at and make a mess of doing what you’re good at.

3 Look for pleasure in the side effects of disaster and pain in the side effects of triumph.

4 Behave informally in formal situations and formally in informal situations.

5 Display your weaknesses and hide your strengths.

6 Adopt a contrary approach whenever possible and never adopt an agreeable approach unless you absolutely have to.

7 Talk to people nobody talks to and ignore people everybody talks to.

8 Experience joy in difficult situations and sadness in enjoyable situations.

N

ow I’ve spelled out my

Dancing in the Darkness

manifesto, I feel as enlightened as a match in an underground tube tunnel. I’ve decided to delve deeper into my philosophical mind and provide some proper guidance on various existential issues for the benefit of humanity…

I

f you’ve got everything, nothing gives you pleasure; if you’ve got nothing, the smallest thing means the world to you. And that principle is the rock on which the good ship

Happiness

continually founders.

Most of us are simply too ambitious when it comes to our own happiness. We assign ourselves parameters. And that’s bad. It’s the worst thing you can do. The more we have, the less happy we are, because, as we get closer to the parameters we’ve assigned, we realise we don’t really

want

it. Even worse than this, placing the ‘happy’ burden on others should be penalised by being put on The Guest List To Hell.

When we achieve our goals, are we happy? They say the journey is better than the stay. But surely life itself is a journey? That’s why, as you try to enjoy

that life of yours, by all means choose the dreamiest destinations but don’t forget to enjoy the

sandwiches

on the plane.

The things that make people happy are the things they expect will make them unhappy. In other words, unhappiness is a result of making the wrong choices. So you could say, ‘the less choice the better’ or, to repeat myself: the trouble with life is there’s only variety and nothing else. In light of this, why not try to enjoy things that happen accidentally rather than chasing happiness?

The years of struggle: lugging band equipment up and down never-ending crooked stairwells, heaving our broken-down Transit van into a sodden petrol forecourt, Pot Noodle picnics in motorway service station car parks. That was

our

journey as a band. A journey with a common purpose. And this common purpose ensured that, despite the hardships, despite the struggle and despite the sacrifice, we experienced much real happiness.

But you shouldn’t value happiness too highly, because if you relate your happiness to serious matters (money, relationships, career and so on) you will never be able to afford it. Instead, try to be happy cheaply.

By all means, have ambitions to conquer the world, but don’t torment yourself with happiness tick-off boxes. Instead try wandering with no shoes (or Havaianas flip flops, if you insist) and collect the goodie bags (of happiness) that fortune bestows.

I think I should stop here before I turn into a bastardised hybrid of Jesus, Buddha and Mohammed. Even happiness isn’t worth the Third World War.

I

t’s easy to imagine that our existence is inevitable. I grew up imagining that significant events were inevitable – my birthday once a year on 15 April and Santa Claus coming from Lapland every Christmas – and I could choose to be happy or sad with such ‘inevitable’ things. Then, before I knew it, the ice-cream melted and Santa never even existed. And lately I’ve noticed how, with hindsight and analysis, events that seemed evil at the time could, in fact, have been avoided – wars, famines, murders, suicides, holocausts and so on.

Now inevitability makes me sad. And frustrated. But, according to my fresh calculations, the word ‘inevitability’ – which seemed to leave no space for challenge – is, in fact, an impostor. So maybe it’s time for a rethink.

To avoid inevitability, you simply need to isolate

the inevitable thing at hand and challenge it. The worst that can happen is an accident where you end up falling flat on your face. And that really isn’t so bad – most of the best things in life happen by accident, after all. So there’s no reason why I shouldn’t take this approach even further by writing an ‘accident’ of a book and waging a war against inevitability.

Anyone can fight against fate. The other day I overheard my Polish cleaner singing one of her songs during her cleaning activities. She’s addicted to music, but claims she has an allergy to hi-fi equipment and needs to sing to herself constantly. I asked her to explain the message of the song to me and she explained, in very plain language, that all good pop songs have the same basic premise, namely that active sex is better than watching porn and bird hunting is better than watching National Geographic. Shakespeare said as much in his ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy, so it must be true. I mean, even if it does turn out to be just one heroic attempt per lifetime, that’s all the more reason to save it for a good cause.

So, I’ve written this book to change the world. Or at least to get some money to save a few elephants and buy some presents for all the women I’ve hurt.