Das Reich (17 page)

Jugie took his codename from that of the air squadron to which he had been attached in 1940. He himself was thirty, a voluble, compulsively energetic Brive businessman of more prosperous bourgeois origins than the general run of

résistants

. He became involved in Resistance as early as 1942, when they were gathering such weapons as they could collect or steal from private and Armistice army sources, and assisting young men to escape from forced labour for Vichy. At that time, some communists worked with him despite the party’s official refusal to have anything to do with Gaullist Resistance. Jugie took part in a few early sabotage operations of 1942–3, killing collaborators and organizing

parachutages

, while continuing to live publicly as a respectable citizen of Brive. He was one of many AS men who throughout the war had to overcome the emotional misgivings of

his wife about the risks that he was taking. On one occasion when he was questioned by the

milice

, he escaped only because his appearance was so shrunken by the consequences of a stomach ulcer that he bore little resemblance to the description of the fleshier figure whom they sought.

One night a team of which Jugie was a member shot a local

milicien

and informer in a Brive bar. They were horrified to discover that the ambulance had removed him to hospital still breathing, possibly able to identify them. It was Jugie who had to snatch an excuse to visit the clinic, where he exchanged condolences with the chief local

milicien

, with whom he had played rugger before the war. It was appalling, this ‘terror on the streets’. Yes, tragically the young man died without regaining consciousness.

Some of their efforts, however, verged on farce. A two-man ‘hit team’ dispatched to the office of a prominent local industrialist and collaborator emptied an entire pistol magazine at him and bolted, only to discover later that not a single shot had struck the target.

By the summer of 1944 the efforts of Peulevé, Poirier and the BCRA had brought thousands of weapons to the Corrèze, and the enthusiasm of the local Resistance had created one of the most numerous departmental movements in France. The British and Malraux had devoted great efforts to persuading the disparate groups to work with each other, and the existence of MUR meant that they were at least aware of each other’s major plans. But the division between the Gaullists and the FTP was beyond bridging. Guedin was among those who bitterly attacked the British agents for arming the FTP, furthering their own entirely selfish ends. Some 5,000

maquisards

in the hills of the upper Corrèze accepted the direction of the French communist party, and had no interest whatever in the wishes or instructions of London.

In the weeks before D-Day, the split became decisive. On Sunday 28 May, Jugie – as the representative of MUR – met ‘Laurent’, a cool, dark teacher from Marseilles who was a dedicated communist

and the FTP’s delegate to MUR. ‘Laurent declared that he had given orders to his men to attack [the main centres of Vichy and German activity] in Brive on the night of 30 May,’ the horrified Jugie reported to Emile Baillely, departmental chief of the

Combat

Resistance movement, and of MUR. He continued:

I told him that we had received formal instructions from Algiers and from London to launch attacks only in open country and at the Dordogne bridges, while carrying out the prearranged rail cuts according to

Plan Vert

, on receipt of the ‘action messages’. Laurent replied that the Allies would never land in France, and that only by taking an independent initiative ourselves could we drive them to parachute us arms and material. Laurent said that he had received no orders from London or Algiers, but that he obeyed the orders of his superior party chiefs. He insistently demanded that I cause the units of my group, both the

légaux

and the

maquis

, to join his troops’ attack on Monday. Naturally I refused . . . I believe it is a matter of urgency to make Laurent’s chiefs see reason . . .

In the days that followed, there was intensive secret discussion between the two factions. The AS leaders made it clear that they would have no part of an attack on Brive, which could provoke horrific reprisals, and contravened London’s repeated injunctions to make no attempt to seize towns at such risk. At another meeting, on 30 May, the FTP renounced the attempt to organize an attack on Brive, but made it apparent that they would be proceeding with their own attack on Tulle, with or without AS support. Amidst considerable rancour on both sides, the factions went their way to prepare for action. On 7 June, Jugie passed a report from Tulle to Baillely:

FTP forces have attacked the German garrison in Tulle. Losses are heavy on both sides. The Ecole Normale where the enemy was billeted has been destroyed. Edith

6

and Maes,

6

on missions to Tulle during the attack, met Laurent at the head of his men. Laurent told Maes that an attack on Brive had been scheduled

for the next day, 8 June. I think it is

urgent

to get the Comité départementale to intervene, because Guy I

6

and Pointer

6

say that armoured units are moving north-westwards, and threaten to pass through our region . . .

Further frenzied activity by the MUR committee members ensured that no AS units made any move to take part in an attack on Brive, although it was learnt that a few groups in the north-east had joined the FTP attack on Tulle. By the morning of 8 June it was apparent that the FTP were too heavily committed in that town to have any chance of moving on to Brive. But the German garrison had heard enough from its own informers to be in the state of acute alarm that the SS found on their arrival.

At 9.30 am on 8 June, as Guedin’s

maquisards

lay in their positions covering the Dordogne bridges, a prominent Vichy official who was one of the most vital sources of Resistance intelligence reported to Jugie that German armoured elements were moving north towards Corrèze to conduct a

ratissage

. He had heard directly from Colonel Bohmer, commanding the German 95th Security Regiment, that the first units were expected in Brive around 2 pm. A prominent Brive

milicien

named Thomine had also remarked briefly to another Resistance informant that ‘Tulle will pay very dearly for the town terrorists’ little joke’.

At 5 pm that afternoon, Jugie passed a further message:

Pierre has just told me that companies Rémy, Désiré, Bernard and Gilbert are in action in the south of the sector against armoured elements of the Das Reich Division. It seems that this column will reach Brive towards 6 pm, because our men cannot hold for long against heavy tanks. I hope you will make Laurent and his friends see reason before it is too late.

The Corrèze committee held a secret rendezvous early that evening at the monastery of St Antoine on the edge of Brive, under Emile Baillely’s chairmanship. Jugie noted:

Some of

Laurent

’s friends insist that the plan for an uprising in Brive be immediately and vigorously implemented, so that it may be liberated like Tulle, and as Limoges may be this evening . . . Baillely, armed with the latest information on the imminent arrival of the Das Reich – delayed on its march by the heroism of the AS–MUR Corrèze brigade – succeeded in dissuading Laurent’s friends from any further folly. Some minutes after the meeting, the first elements of the Das Reich arrived in Brive.

Jugie’s notes gave an indication of the bitterness with which the argument raged through those days, with mutual charges of betrayal and cowardice flung and contradicted, when the AS refused to fight in Brive to relieve the pressure on the FTP in Tulle. It is an interesting aside on the nature of Resistance in the days after the Allied landing that none of the local SOE officers was invited to take any part in the debate. These decisive questions were fought out entirely between Frenchmen. Before the event and subsequently, French Section’s agents discussed, advised, persuaded and argued, but neither here nor in any but a handful of departments of France did the British or Americans have a chance to exercise executive authority. In the Corrèze, indeed, they firmly resisted the efforts of De Gaulle’s BCRA to take a hand in directing their operations.

Reading Jugie’s report, it is also essential never to lose sight of the chasm between his impressive references to companies and brigades and the reality on the ground of clusters of half-trained, half-armed boys among whom it was intensely difficult to maintain discipline in camp, far less in action. Rather than diminishing their achievements, these difficulties only serve to enhance them.

Early that evening of 8 June, at the Café des Sports in the centre of Brive a courier from Marius Guedin reached Jugie. He reported that the AS officer was furious to hear that trains were still

running on the line north of the town, towards Uzerche. Would ‘Gao’ act immediately to halt them? Jugie fetched his bicycle and began a long ride around the town. First, he briefly visited three men of his circuit – Lescure, Briat and Chauty. They would meet him outside the town. Then he rode a mile or two to the farm of a man named Levet. Levet was one of many thousands of Frenchmen who did nothing spectacular or worthy of decoration during the Occupation, yet took terrible risks to support Resistance. Under the straw in his barn was a dump of explosives and detonators. Jugie rapidly assembled four ‘loaves’ of around a quarter of a pound of

plastique

apiece, and took a bunch of the deadly little grey detonators. Strapping his cargo in the bag on the carrier of his bicycle, he rode briskly to the rendezvous with the others. Well-distanced to avoid suspicion, they hastened onwards through the soft evening sunshine to a point where the railway dropped into a wood.

They passed a squad of French workmen working under German guard to repair the last section of line they had attacked. A mile or so beyond, they reached their target. Briat and Chautry held the bicycles and kept watch while Lescure and Jugie worked the charges under the track, one set to each of the north- and south-bound lines. They pushed the detonators into the soft lumps of explosive, connected them with bickford cord, and scrambled hastily into the wood, trailing cable to the electric detonator. Suddenly, to their consternation, they saw a peasant leading an ox cart across the line only yards away. He had resolutely resisted the pleas of Briat and Chauty to halt, insisting dourly that he was only going about his business. Moments passed, and a girl rode up on a bicycle. She was the daughter of the railway-crossing keeper, and Jugie had known her brother in the army. She said that she could hear gunfire in the distance. Jugie waited a few moments for her to disappear from sight, then twisted the exploder. One charge detonated hurling a twisted section of line into the air, but the other failed to go off. They ran to it, fumbled hastily to replace the cord, and fell back. They were careless. Jugie was slow

to take cover as he fired the charge, and the blast, together with a deluge of stones from the permanent way, caught him where he crouched. He lost his hearing in one ear for life. But the line was blown, and there was still no sign of any Germans. The four men slipped swiftly back into Brive. The forward elements of the Das Reich had moved on. The Der Führer regiment was rolling up the long hill that led the way to Limoges, where its tired troopers arrived at last in the early hours of 9 June. The guns and miles of supporting vehicles were still moving steadily through Brive, towards their lagers on the Uzerche road. Major Heinrich Wulf’s reconnaissance battalion, the

Aufklärungsabteilung

, followed by Colonel Stuckler and divisional headquarters, was closing rapidly upon Tulle.

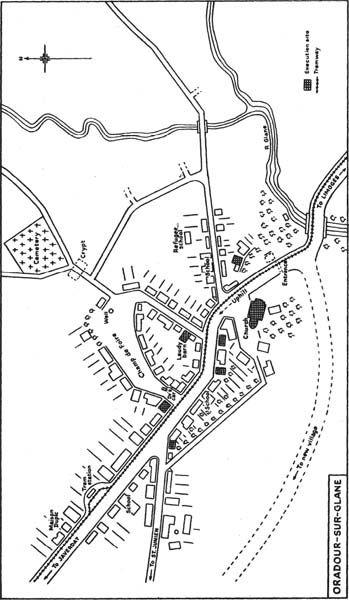

The town of Tulle clings to the steep hills of the Corrèze like a precarious alpinist, the shops and houses of its 21,000 inhabitants perched wherever nature will allow them a foothold. The bustling river Corrèze falls through its midst, banked on each side by walled quays and the main streets. On the hillsides above rise three large schools, the barracks, the prefecture and the town hall. On the plateau at the southern end of the town are clustered the station, the big arms factory which is the town’s main employer, and a knot of shops, houses and small hotels. Tulle is a grey, architecturally undistinguished place, though some think well of its cathedral. It has suffered its share of historical misfortune: twice sacked by the English in the Hundred Years War, devastated by the Black Death, retaken by Charles V in 1370, and defended by Catholics in 1585.

The department of Corrèze was a pre-war radical stronghold. Of its four deputies elected in 1936, three were socialist and one was a communist. Communism in France does not mean quite what it does in Moscow. Many of its supporters see no inconsistency in being energetic businessmen, proud

propriétaires

who are married in church and have their children baptized. In the country, French communists have always been ‘leaders of a local faction rather than agents of Moscow’, in Brogan’s words. But the communists of the Upper Corrèze were always well organized, and it was not surprising that when Russia entered the war and the French party reversed its policy of accommodation with the Occupiers, a strongly based communist Resistance developed around Tulle.