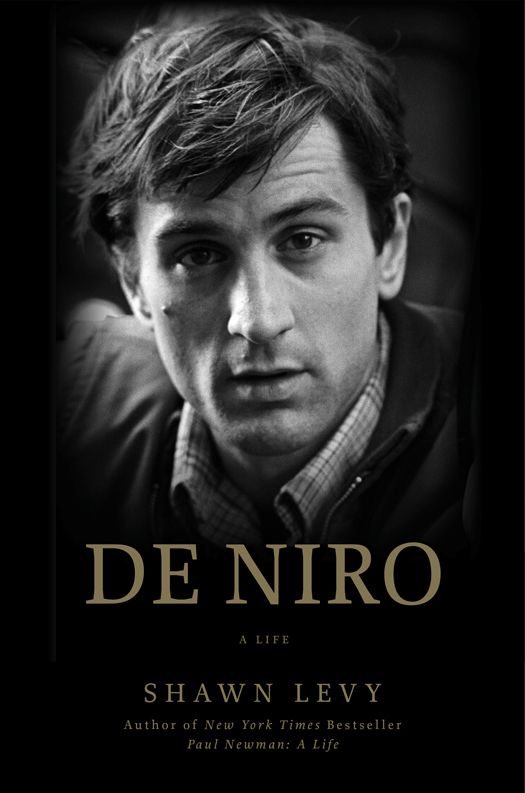

De Niro: A Life

Authors: Shawn Levy

LSO BY

S

HAWN

L

EVY

Paul Newman: A Life

The Last Playboy: The High Life of Porfirio Rubirosa

Ready

,

Steady

,

Go! The Smashing Rise and Giddy Fall of Swinging London

Rat Pack Confidential: Frank

,

Dean

,

Sammy

,

Peter

,

Joey and the Last Great Show Biz Party

King of Comedy: The Life and Art of Jerry Lewis

Copyright © 2014 by Shawn Levy

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Archetype, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

Crown Archetype and colophon is a registered trademark of Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin for permission to use materials contained in the Robert De Niro collection and the Paul Schrader collection.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Levy, Shawn.

De Niro / Shawn Levy. — First edition.

pages cm

1. De Niro, Robert. 2. Motion picture actors and actresses—United States—Biography. I. Title.

PN2287.D37L47 2014

791.4302’8092—dc23

[B] 2014016798

ISBN 978-0-307-71678-1

eBook ISBN 978-0-307-71680-4

Jacket design by Christopher Brand

Jacket photography: Steve Schapiro/

©

Corbis

v3.1

For my sister

,

Jennifer

,

and her beautiful family

S

PRING 2012, AND, AS FOR DECADES, THE ATTENTION OF THE

world’s film lovers is focused on the onetime fishing village of Cannes, France, and its annual film festival, one of the most prestigious and celebrated cultural events of the year.

On a muggy Friday evening, the air outside the famed Palais des Festivals is plangent with the hum of music written nearly thirty years prior for a movie about hunger, yearning, innocence, violence, crime, betrayal, and memory.

Once Upon a Time in America

was an epic both in its creation (a dozen years of writing, eleven months of shooting) and in the vision of its director, Sergio Leone, whose preferred cut ran almost four and a half hours. The film premiered, slightly shorter than that, at Cannes in 1984 to a rapturous reception—a fifteen-minute standing ovation, one observer recalled. But its post-festival fate was a legendary catastrophe. Distributors hacked it almost in half and restructured the narrative, virtually ensuring negative reviews, tepid box office, and a kind of professional oblivion for Leone, who died five years later without directing another film. Over time, though, the movie grew in reputation—in part because of the posthumous stature of its director, in part because increasingly faithful versions of the original cut were released—and it came to be considered by some of its champions as the acme of its genre, the American gangster movie.

And so on this May evening twenty-eight years after its debut, a restored

Once Upon a Time in America

, twenty-five minutes longer than the version that first premiered at Cannes, will be shown in the very

same theater where the original screened—as good an occasion as any for a typically deluxe Cannes gala.

In the dying daylight, with Ennio Morricone’s luxurious and ghostly score on the PA system, the movie’s star, Robert De Niro, climbs the legendary red carpet of the Palais to present the film.

De Niro has ample reason to feel nostalgic. Eight times previously he has visited Cannes in support of a film in which he appeared; twice his work garnered the festival’s top prize, and just the previous year he served as president of the festival’s jury. It has been, in many ways, a lifelong haunt.

And haunting too, surely, would be the absence of Leone, the reunions with his co-stars, some of whom he hadn’t seen since they’d made the film together, and, of course, the spectacle of his younger self on-screen.

But De Niro has experienced all of that many times before, and he has accrued a reputation for stoicism and inscrutability, as well as a detached, even disinterested air about such proceedings.

Something pricks at him on this evening, though, unloosing feelings of the sort he usually reveals only within the strict confines of a movie role or in the hidden chambers of his private life. As he mounts the stairs, he has tears in his eyes, and photos will circulate of him standing in a tuxedo beside his wife with his face clenched in an effort to control his emotions.

Maybe it’s the music, Gheorghe Zamfir’s pan flute soaring sweetly and sadly over a mournful bed of strings.

Maybe it’s the weather: stuffy, wet, thick.

Or maybe it’s the knowledge that the chance to make a film like

Once Upon a Time in America

is exceedingly rare and impossible to duplicate once it is gone, the knowledge that movies, like life, can pass us by.

Such a sentiment would certainly mesh with the rueful themes and star-crossed history of Leone’s film.

And it would serve, too, as an apt starting point for any discussion of the life and work of Robert De Niro.

W

HEN HE BEGAN

shooting

Once Upon a Time in America

, Robert De Niro was, almost without question, the most powerful and compelling actor in world cinema. This is an enormous claim, considering that such titans of screen acting as Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, Jack Nicholson, Jon Voight, Robert Duvall, and Gérard Depardieu were still ascendant at the time, and such older masters as Jack Lemmon, Paul Newman, Max von Sydow, Peter O’Toole, Michael Caine, Marcello Mastroianni, and even Laurence Olivier and (when he could be bothered) Marlon Brando were still in the game.

But the Robert De Niro of 1982 stood apart even amid such auspicious and accomplished company.

In the spring of 1981, he had won his second Oscar in six years for his role in

Raging Bull

, a performance that was immediately recognized as one of the greatest ever captured on film, built of astonishing physical transformations and raw, wrenching emotions. The previous decade had seen him rise quickly from career in shaggy independent films to the center of such landmark movies as

Mean Streets

,

The Godfather: Part II

(his first Oscar-winning role, in which he spoke almost entirely in a Sicilian dialect that he learned for the film),

Taxi Driver

,

1900

, and

The Deer Hunter.

He worked with the cream of Hollywood’s cohort of young Turk directors—Brian De Palma, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Cimino, and especially Martin Scorsese, with whom he made five films in ten years—as well as with Bernardo Bertolucci and Elia Kazan. His pair of Academy Awards had been accompanied by two additional Oscar nominations, four BAFTA nominations, and a combined seven prizes from the top critics groups across the nation.

He was a master chameleon and an astonishing risk taker, diving as deeply into his roles as any Method actor ever had and coming through them stronger, bolder, better. He had a supernatural, mysterious air and conveyed danger, poetry, sex, loneliness, daring, intensity, surprise, and thrills. He was as exciting a screen actor as had been seen since the heydays of Brando and James Dean. His name on a movie marquee was a galvanizing draw. And at age thirty-eight, he was just getting started.

But thirty years later it could be hard sometimes to see De Niro’s early glories through what had become the muddle of his later career.

The shift was gradual. For more than a decade after

Once Upon a Time

he continued to appear in high-quality projects with notable collaborators:

Brazil

,

The Mission

,

Angel Heart

,

The Untouchables

,

Midnight Run

,

We’re No Angels

,

Mad Dog and Glory

,

Heat

,

Wag the Dog

,

Jackie Brown

,

Ronin.

He made three more movies with Martin Scorsese—

Goodfellas

,

Cape Fear

,

Casino

—and made his directorial debut with the tender and substantial

A Bronx Tale.

Over time, he gravitated toward smaller roles, working in ensembles or in cameos rather than carrying whole films, but he continued to be recognized by his peers, receiving Oscar nominations for

Awakenings

and

Cape Fear

. And he continued to be one of American cinema’s most watched, imitated, and respected actors.

He didn’t, however, have a real blockbuster hit until 1999, when the outright comedy

Analyze This

became the first film of his career to gross more than $100 million (by comparison, Arnold Schwarzenegger and John Travolta—and, more to the point, Dustin Hoffman and Jack Nicholson—had each reaped that sum at least five times by then). It was a clever movie, making comic hay of De Niro’s tough-guy aura and giving him the chance to demonstrate a funny bone that he’d shown as far back as the 1960s but had long suppressed under his serious Method-actor veneer. The following year, De Niro appeared in

Meet the Parents

, a comedy that was neither as clever as

Analyze This

nor as carefully built around his on-screen persona; naturally, it was an even bigger box office hit. And it presented De Niro anew—for audiences and moviemakers—in a way that would muddy his public image and threaten the impact of his legacy.