Death: A Life (15 page)

It was

the Sumerians who kicked things off. Imagine, if you can, an entire race of people grimly obsessed with the weather and you get some inkling of ancient Mesopotamia. Such meteorological obsessions seemed to stem from the fact that nascent society had located itself on a monotonous landscape of mudflats and marshland, the tedium of whose prospects was matched only by the certainty of its inundation. “Is it raining?” was the fashionable conversational entrée for more than fifteen hundred years (when it was eventually supplanted by the typical forthrightness of the Roman, “What do you do?” which retains the position to this day).

Despite being perpetually damp or drowned, the Sumerians managed to invent the stylus, a remarkable innovation that transformed not only learning but also warfare. For centuries anything that left a mark had traditionally been classed as a weapon, and for some time the pen wasn’t just mightier than the sword, it

was

the sword. When the Sumerians discovered that such instruments could be used not just for slaughter but for scholarship, it radically reshaped their culture (although the rehabilitation of the typewriter, which they had invented as a particularly gruesome bludgeoning weapon, would not take place for many thousands of years).

I noticed that the Sumerians were one of the first groups of humans to establish a firm belief in an afterlife. You would have thought that, considering the unremitting misery of their lives on Earth, they’d be sick and tired of Life in general, especially an afterlife. But they were gluttons for punishment, and with an imagination saturated by the dampness of their unfortunate situation, the Sumerians imagined a hereafter in which they would eat dust and clay in a dark room, forevermore. The idea of a happy afterlife, like the idea of a happy Life, was simply beyond their conception.

Ancient Sumerian Warriors Depicted with Large Battle Typewriter

(left)

, and Small War-Bottle of Correction Fluid

(right)

And the gods they had! A bunch of second-rate minor elementals without a sliver of personality between them. There were gods of streams and rivers, of rivulets and creeks, of drizzle and humidity, all of whom were literally lining up to drown the Sumerians. At least these gods didn’t ask me for any favors and were moderately scrutable, unlike Him. For instance, when King Sargon was overthrown by the barbarians, everyone knew that the god Enlil had punished the land because Naram-Sin, a king of Sargon’s line, had sacked Nippur, plundered the Ekur, and humiliated Lugal-Zage-Si, such that when the Gutians invaded Akkad, Ur-Nammu was forced to seize power from Utukhegal. It was plain for all to see.

As far as I was concerned, complex motives were unimportant as long as any major massacres were noted in the

Book of Endings

with plenty of time for me to prepare. Yes, I thought I had it all figured out in Sumeria, all under control. Little did I know that in those moist lands my existence would be changed forever.

I remember

the day well. How could I forget? The usual prognostications, fearful sacrifices, and portents of divine satisfaction had been swiftly followed by the customary great flood, and the temple priests, who had relocated themselves to high ground just in time, were questioning the quality of their prophetic entrails. The storm was still raging as I glided about the pale, bloated bodies that scattered the flooded plain like confetti. It was slow work as schools of Fish Supremacists crowded around the bodies in order to heckle the dead.

(Fish Supremacists thought that anything that was not a cold-blooded aquatic vertebrate with two sets of paired fins and a body covered in scales was an inferior being. They had become a political movement around the time of the Great Transition, when some fish decided to leave the water for the land. There had been much talk of “quitters” and “degenerates” among the still-fish population, and the annual floods were seen as a settling of scores with the earthbound.)

Fish of Intolerance.

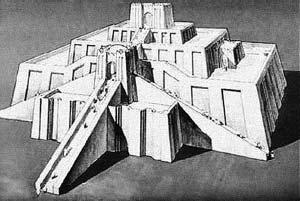

It was while extricating the soul of a well-known fisherman from a gang of rowdy carp that I heard a scream from above. I had, of course, heard many screams in my existence, and one grows used to their character, but this was different. Some screams are emphatic, challenging, precursors to a deadly action. Others are resigned, tired, bored, a by-rote shake of the fist at the characteristic remorselessness of the Universe. But this scream was delicate, graceful, a bloodcurdling shriek of pure unadulterated beauty ringing clear through the thunder and rain. It seemed to be emanating from the peak of the Great Ziggurat of Ur.

I looked in the

Book

but there were no fatal plunges scheduled from the Great Ziggurat of Ur until the following week, when the temple priests would be hurled from the summit in order that

their

entrails be studied. Nevertheless, this scream commanded my attention so much that I had no choice but to explore its source.

The Great Ziggurat of Ur: Twinned with Angkor Wat?

Arriving at the top, I saw that the screamer was a woman. She was dangling upside down from the peak of the Ziggurat, her robes and hair fluttering in the wind, her left sandal fortuitously snagged on a spur in the rock.

“This is peculiar,” I remember thinking. “How is she going to survive this?” As I walked from side to side contemplating the strangeness of the situation, something even more peculiar happened; I noticed her eyes were following me.

During the Biblical Age I had decided to make myself invisible to the living. The reason for this wasn’t misanthropy, far from it; rather, it was because my reputation had grown to such an extent that whenever I appeared in front of a group, the very sight of me caused panicked stampedes. Of course, I had only been drawn to the group to collect the souls of those crushed in the mad dash away from me. This made my head hurt when I thought about it, so to make things simpler I had grown imperceptible to all things. Except, it seemed, this woman.

I ducked into a stairwell, but still her eyes followed me. I ran from one end of the Ziggurat’s terrace to the other, but still she watched me. I started leaping in the air, making large star-jumps, to make sure her eyes were not following my course by chance, but this only started her giggling.

“What

are

you doing?” she said.

“Um…” I hesitated.

“Ur, actually,” she replied, eyeing me carefully. She spoke very calmly despite her precipitous position. “I’m Maud.”

“You can see me?” I asked, checking over my shoulder to ensure there was no one standing behind me.

“No.” She sighed, flicking her hair nonchalantly out of her eyes. “But I do find the only state in which I can bear to talk to myself is while hanging upside down from the Great Ziggurat.”

She flashed a smile at me. Even upside down she seemed to be an unusually pretty human.

“Now look,” she said quite abruptly, “why not just unhook my little sandal from this tedious brick and let me smash my body to pieces on the stones below?”

I didn’t know what to say. Of course, many things had taken their lives before. In fact, suicide was a way of life for many creatures. I knew hundreds of unhappy radishes who had uprooted themselves in despair at their allotment in life. But never had I been directly asked for assistance in ending things. Life was usually fragile enough not to require my help.

“I don’t think I can do that.”

“I’d really much rather be dead, you know.”

“But it’s against the regulations,” I said. I flicked through the

Book.

“You’re not due to die for another twenty-three years.”

“You are Death though, aren’t you?”

“Well, yes.”

“Then what are you doing here?”

I wasn’t quite sure of that myself. In fact, I wasn’t sure of anything when I looked into those deep brown eyes of hers.

“Look,” I said, pulling myself together, “yes, I am Death, but I don’t interfere. You’ve got to do that yourself.”

“Well, that doesn’t sound much like Death to me,” she said. “And you’re a little shorter than I expected, although it’s hard to tell with you being upside down. Maybe, in fact, you’re taller than I expected. You know, my soothsayer said I’d meet a tall, dark stranger one day…”

I should have walked away. It was not as if I was lacking for work. Yet I couldn’t tear myself away from this woman, poised between life and me.

“…but I said, ‘Enheduanna’—Enheduanna’s my soothsayer’s name—I said, ‘Enheduanna, we’re in the middle of Mesopotamia, of course he’s going to be dark, and as for tall, you think tall is anything over four feet.’”

What was she talking about? What was I doing listening to her? Why did I not walk away? Looking back on it, I realized my fate was sealed from the moment she said her next words: “Pretty please?”

And so, feeling as if my body was being controlled by some mischievous power (I checked with Father later and he said he had nothing to do with it), I walked over to her and, looking both ways in case anyone was watching, delicately flicked her sandal over the edge. I watched as she plummeted to her doom.

“Thank youuuu…,” she cried. There was the sound of a small thump. I hurried down the Ziggurat.

“Thanks again,” she said, as I bent over to scoop her soul out of her bloodied and broken body. It was more radiant than any other I’d ever seen before. “That is a relief, I can tell you.”

“Why did you want to die so much?” I asked.

“Oh, you know—boy comes of age, boy meets girl’s family, girl’s family draws up marriage pact with boy, boy complains girl’s dowry is too small, girl’s family says it is more than enough, boy says girl will die an old maid, girl’s father throws in an extra camel, boy says that’ll do nicely, father tells girl to cheer up and sprinkle herself with aromatic cedar oil, boy meets girl.”

It was an age-old tale. But one thing still troubled me.

“How could you see me?”

“Well, you were just standing there.”

“But people aren’t meant to see me.”

“Why ever not?”

I tried to explain the panics I had caused, and she nodded her head in sympathy. I had a strange urge to keep talking, but already the Darkness was starting to encircle her. I slapped it back.

“Would you care…,” I asked her shining, lustrous soul, as a strange wave of nervousness rushed over me, “to go for a walk?”