Death: A Life (35 page)

“Yes, yes, quite right,” boomed God, “inscrutable, and ironic. So there you have it. Who knows what We’ll do after that. Probably something equally crazy. Maybe We’ll give everyone four legs. Anything to idle away a few hours, really. Killing time is simple, but killing eternity takes forever.”

I stood there and let them speak.

“Anyway, by way of publicizing the Second Coming and the life of the world to come,” boomed God, “We were thinking that Jesus should fight you. There should be a little back and forth, you should get Him in a headlock, say, and it should look like it’s all over when Jesus will suddenly flip you over His head, leap onto the ropes and perform His…what’s it called again, Jesus?”

“Do you mean My ‘Battle Stations of the Cross’?” beamed Jesus.

“Yes, that’s the one,” boomed God, turning back to me. “This will destroy you completely.”

“I’m going to take you down to downtown,” beamed Jesus, “and show you around, you clown.”

“Yes, thank You, Jesus,” boomed God, turning back to me. “I do think I let Him stay on Earth just a little too long, don’t you? Anyway, the match will be watched by every being in Creation, either in the stadium We’re building—did you see it?—or, for those in Hell or Purgatory, on pray-per-view. Okay?”

“But I think I’m doing good work on Earth, necessary work.”

“Yes, We’re sure you are,” boomed God. “But if everyone is going to live forever and ever, We hardly need you now, do We?”

“I can do other things,” I said. “I don’t just have to do dying….”

“Yes, yes, We’re sure you could,” boomed God, “but We thought it would make people rather nervous if you were loitering around while they tried to enjoy eternity. You’re hardly inconspicuous, you know.”

“So that’s it, is it?” I said. I suddenly felt strangely calm faced with my own extinction. I guess I had seen so many endings I had become completely inured to them, even my own. I looked at the Darkness fondly. Soon I would be sending myself into it forever. I consoled myself that there were worse ways to go. At least I still had my dignity.

“Tell him about the other thing,” beamed Jesus.

“Oh yes. Jesus thinks that all of Creation would like it very much if you winked out of existence in, say, Round Two. He thinks Creation would like that a lot.”

“Round Two, you’re through!” beamed Jesus. “You’re so old, I’m so new!”

“Yes,

thank You,

Jesus,” boomed God. “So why don’t you come back in seven days’ time and We’ll wink you out of existence.” He and Jesus picked up Their paddleball rackets.

I was astounded.

“At least make it a fair fight?” I pleaded. “You owe me that much.”

“We don’t owe you anything,” beamed Jesus. “On the contrary, since We created you, it is you who owes

Us

everything.”

“If—”

“No ifs,” beamed Jesus.

“But—”

“No buts,” beamed Jesus.

There was the sound of a strangled boom. God had got Himself entangled in His racket’s elastic again.

“Let me help You, Father,” beamed Jesus.

“I can deal with it Myself, thank You very much, Jesus,” boomed God frustratedly.

“Exactly,” beamed Jesus.

I turned my back on the divine beings and sloped away from the Parliament. Nobody seemed to pay me much attention. I walked through the Gates of Heaven where Peter was now sitting, his hands wrapped in wool, as his mother knitted.

“So you’ve heard the news,” said Peter, embarrassedly. “I am sorry.”

“That’s okay, Peter,” I said.

“Good luck in the fight with Jesus.”

“Thanks, but I don’t think it’ll be of much use.”

“Oh yes. Yes, quite.” Peter paused. He was struggling to formulate a question. “Any…idea in which round you might…disappear?”

“Round Two,” I said. “I’m being phased out in Round Two.”

“Thanks, Death, you’re a real pal.”

As I swooped back down to Earth I thought about my destiny. It seemed strange that after all the hard work I had done on Earth, after nearly losing myself forever to my addiction with Life, and after my painful rehabilitation at the clinic, that I was now being “phased out.” Such an ugly phrase. It lacked a sense of finality, the clear cut that separated the living and the dead. If only I could be shot through the heart, have a grand piano drop on my head, be guillotined, I would not find it quite so bad. Instead I would slowly fade from sight, like a bad memory. I didn’t think my own demise very ironic at all. But it did seem poetic, albeit like the kind of poetry that doesn’t rhyme or make sense.

Despite the imminent arrival of the Second Coming, and the subsequent mass resurrection, I continued with my job. As it had at the beginning of my career, concentrating on the dead calmed me—the slip-sliding of the souls, the empty bodies, the quiet of the void acted as a balm to my worried thoughts. Of course, I couldn’t help but tell some of the souls how lucky they were to die when they did, as soon no one would be dying at all. When the souls heard this, they felt rather pleased with themselves—after all, as once-in-a-lifetime experiences go, nothing really compares with dying—and became very friendly to me, saying how sorry they were that I was going. Some even said they’d put in a good word for me with God, but I told them not to worry. I was ready to die.

There was not an inch of the earth that I had not covered in my existence, but I thought now would be the time to visit those places that held a particular significance for me. I went back to where Eden had been and found Urizel was still there, vigilantly guarding it, even though Eden had been devastated and was now home to a smelting works. It had been so long since Urizel had been sent to guard it that I rather suspected Heaven had forgotten about him entirely, but Urizel did not seem unhappy.

“Never let it be said that Urizel doesn’t know how to follow an order,” he said to me, as he swept back wave after wave of health and safety inspectors who tried to pass through the factory gates. “None shall pass!” he screeched.

There had been many changes, I thought to myself, as I surveyed the world that had been my home for so many millions of years. Volcanoes that had once been the sites of sacrifices and suicides were now scattered with complacent tourists, who only rarely slipped and fell into the bubbling lava. Hospitals that had once been the great shipping stations into the Darkness now dangled the sick and dying just out of my reach, with a marionette’s assortment of tubes and catheters. It seemed a shame to leave Earth just as Plutonium and Uranium had discovered their métier, and when bungee jumping and hang gliding would soon become popular activities. There were so many of you now, so many ways to go. At times it seemed as if I was being tempted to stay by the ever-growing varieties of your ends. How fitting, I thought, that my farewell should come amid such a cornucopia of slaughter.

My only regret was that the one person I would most like to have spent my last hours with was nowhere to be found. I visited the site of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, where Maud and I had originally met. The faint echo of her scream—that glorious first scream—seemed to be imprinted on the landscape, imbuing the rocks, the sand, the wind itself with her very essence.

I shook myself free from this reverie and opened the

Book of Endings

to see who was next. I was somewhat troubled to realize I had reached the last page. I stole a glimpse at the last name on the list. It was mine. A shiver went through me. I slammed the

Book

shut.

I was really going to die. I was really going to disappear forever. How terrifying to be able to measure out my existence in mere hours. There would be no more souls for me, no more thoughts, no more Darkness, even. There would be no more—

“Excuse me, are you Death?” said a small voice.

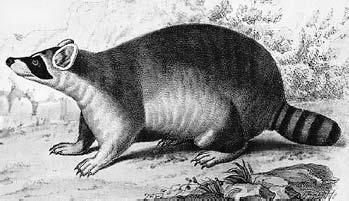

I looked down and saw a small raccoon standing on its back legs looking at me. Its head was slightly cocked.

“Er, yes.” The shocking realization of my own death must have made me visible again.

“Hello,” he said as he extended a paw for me to shake. “My name’s Phil the Raccoon. I’m named after an ancestor of mine—Phillip the Raccoon. They say you two were friends. You let him chase after frog souls when he was dead. If he was anything like I am, I know he would have loved that.”

“What do you want?” I said, slightly perplexed. I glanced quickly at the

Book of Endings.

I didn’t want to spend too long looking at it. “You’re not due until tomorrow afternoon.”

“Really?” said the raccoon. “What do I die of?”

“I can’t tell you that,” I said, largely because I didn’t want to look in the

Book

again.

“Distemper, I bet,” said Phil the Raccoon. “Or maybe rabies. I’ve been feeling dry-mouthed all week. Then again, maybe that’s because I’ve been looking all over the world for

you.

Word on the street has it that you’re not going to be around here much longer. Me and some of the other woodland creatures held our regular Tuesday night séance the other night. Everybody in the spirit world’s talking about Death being phased out.”

“Yes, yes, it’s true,” I said. There was no need for it to be a secret.

“I also hear that there’s some big money being put on you to take a fall in Round Two? And I mean

big

money. Know anything about it?”

“How do you know about that?”

“Come on, Death, don’t be so naïve. There’s no gambling in Heaven. Where do you think the angels place their bets? Right here on Earth is where, and Phil the Raccoon provides a full and discreet nocturnal bookmaking service for those of the saved who accidentally wander out of Heaven while everyone’s asleep.”

Raccoons. Always with their schemes. I had once met a raccoon who had attempted to assassinate Archduke Rudolph, the Crown Prince of Austria, in order to inflate the price of strudel, which he had sold short. As it was, he was caught by the royal bodyguards as he clambered into the archduke’s bedroom, intent on savaging him in his sleep. The raccoon had been turned into a hat, which became all the rage in late-nineteenth-century Vienna. Strudel prices, however, had remained low.

Raccoons: Good Schemers, Excellent Headwear.

“Well, why do you want to know about the fight?” I asked.

“Call it a surfeit of Free Will,” said Phil the Raccoon, “or maybe I’m just looking after my best interests. I had an angel in the other day who was putting everything he owned on you going down in Round Two—money, an old harp, a girdle, and the pearl handles he’d filched from some gates. This match could bankrupt me! But more than this, I’m a moral creature. I don’t like the idea of the fix being in for anything. What kind of a world would it be if everything was predetermined? Nobody would want to wager on anything.” He looked at me straight in the face. “Doesn’t it make you mad?”

“Not really.” I sighed; I had resigned myself to my fate.

“Really?” said Phil the Raccoon.

“I admit,” I said, “that throwing a wrestling match with the Messiah may not be

exactly

the way I would have chosen for myself. But isn’t every existence in Creation a fixed match of sorts, a futile combat against insurmountable odds?”

“Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear,” said Phil the Raccoon. “That’s hardly the attitude to take.”

“I am Death,” I reminded him. “I’m not really meant to be very positive.”

“It could be worse,” said Phil the Raccoon.

“I don’t quite see how,” I replied. “After all, I’m dealing with an all-powerful being with a split personality.”

“Well, look,” said Phil the Raccoon, “give me twenty-four hours to come up with a solution. Maybe this doesn’t need to happen.”

“What do you mean?”

“Maybe you don’t have to die, Death.”

I looked at the small, bushy-tailed mammal gesticulating on the ground in front of me. Was this really all that stood between me and extinction? Was

this

my final hope?

Last Judgment