Death be Not Proud (7 page)

Read Death be Not Proud Online

Authors: C F Dunn

Â

The sun had just set, the roofs of the buildings silhouetted against the pale salmon sky to the west. It threatened to be cold again and I made my way home as the shops began to shut. Christmas lights hung in abeyance across the street, waiting like a widow to shed the garb of mourning and be clothed once more in light. I had a lead on the name and the place; now all I could do was follow its thread, and hope that where it led, I wanted to follow.

4

The Box

Man is no starr, but a quick coal

Of mortall fire.

G

EORGE

H

ERBERT

(1593â1633)

I needed to concentrate fully if I hoped to make any inroads on the negligible information I had tracked down. As I entered the broad hallway, the signature tune of the early evening news blasted from the television in the sitting room, the house otherwise quiet and at peace with itself. I started for the stairs, then changed my mind, doubling back to make my presence known to my parents and to forestall any questions.

They looked up as I came in, my mother's hands still twitching the wool around the fine knitting needles as she smiled at me, working all the time, the air around her strangely bright as if she were back-lit like an exhibit in a gallery. I made a mental note to have my eyes checked. Our fat tabby cat waddled over to greet me, head-butting my leg in the eternal quest for food and attention. I had barely seen him since coming home; I bent down to stroke him.

“Hello, Tiberius â how's things?” I scratched behind his ear just the way he liked. “Hi, Mum, Dad.”

Click, clickity-click

, Mum's needles went without pausing.

“Hello, darling, how did that go?”

“Yep, Beth's fine, so are the children, and Rob said to say âHello'. Oh, and I forgot the croissants â sorry, Dad. I've left the money in the hall.”

I didn't wait for an answer, and I heard him grunt behind my back; I imagined a dark cloud with incipient rain hanging over him. Mum's voice followed me into the dining room through the door.

“Have you eaten? Your father's made a wonderful casserole for this evening.”

“I've had coffee, thanks, and I'm going to grab something to eat now, so don't worry about supper for me â I've too much work to do.”

“You don't drink coffee, darling, and there's tea in the pot,” Mum called after me.

I raided the stone-lined pantry set into the thickness of the wall, the temperature only a degree or two above the cold night air outside. A slab of Lincolnshire pork pie, an orange, and a handful of grapes balanced on a tea plate would have to do for now, as neither hand would support any more weight. I grabbed a half-mug of tea and collected my bag on the way back through the hall. Tiberius followed, trotting upstairs beside me.

Â

The old tailor's box had once held a man's dress shirt, back when gentlemen still expected to wear stiff wing collars and to never venture forth without gloves and a hat. Now the shabby box I retrieved from the top of the cupboard squeezed in beside the fireplace contained the tatty remains of the papers my grandfather had specifically left to me in his will.

I sat cross-legged on my bed and removed the lid, the tired cardboard smelling faintly of his cigar smoke and mothballs.

Tiberius jumped up beside me, his long tail flicking in my face; I tickled his ears and he settled in a heap, half hanging off my lap, and began to purr. In lifting off the translucent layer of tissue paper that protected the contents, my heart suddenly scuttled unevenly. I breathed slowly, easing out the anxious niggle, and it settled once again to its regular beat. Here, in this old box, had lain the portion of Ebenezer Howard's unfinished transcriptions of the journal, along with the other papers Grandpa had picked up in the auction, and his notebook containing his research. I remembered him writing in the fat, foolscap book, its red cloth spine and marbled covers stained with ink. I had an image of him sitting at his desk in his bedroom by the window in the sun, a silver bowl with large, foil-covered penny toffees by his elbow, and a copper ashtray the colour of my hair. An inevitable cigar smouldered, the acrid fragrance spiralling into the rays of morning light. The toffees were his way of cutting back on the last of his vices. When very young and not too heavy, I crawled onto his knees and he would unwrap the gold discs for me which, crammed into my mouth, would keep me quiet as he told me the stories of our past, his bristly chin grazing the top of my head, my ear against the slow beat of his dying heart. When I became sleepy and had stopped listening, my grandfather would continue writing in his book, the movements his arm made as it crossed the page a soothing rocking that lulled me to sleep.

Tiberius stretched out a paw and padded my arm. I looked down at him and he gazed back with his enormous green eyes as I stroked his warm head. The central heating struggled to heat the top floor and, tonight, frost would line the roof tiles and attempt to seep through the fragile frames of the windows. I tried to remember where I had last seen a fan-heater in the house.

Nanna and Grandpa shared the room opposite mine in the years before he died. It faced east over the many pitched gables and slates of the old roofs behind our tall house, and the early morning sun would ripen the colours of the faded wallpaper in the summer. It smelled of my grandmother â the clean talc-and-medicine smell that seems to accompany old age. The room was as she had left it when she had been taken ill; I felt at once comforted by her presence but also an intruder in what had been her world. I retrieved the fan-heater from under her bed and retreated to my room, wrapping my blue rug around my shoulders, as much for the memory it brought me as for the warmth it would offer, and started to organize my thoughts.

Grandpa's familiar thin, spidery writing in dark-blue ink scored each page in meticulous formations, dates in red and place names in capital letters underscored once for a parish and twice for a town. It was a system I still used. As part of my own research I had read Grandpa's notes, of course, but they represented nothing more than background information and a short-cut into the world of the seventeenth century. Now that I added purpose to my labours, each word held the potential to transform the mundane into a revelation.

My grandfather concentrated his research on the Richardson family rather than the Lynes, whom they had served as stewards, so I expected that much of the information he gathered would be largely irrelevant for my purposes. Apparently, Nathaniel Richardson had been the third generation of his family to act as steward. His grandfather â also Nathaniel â had been employed by the Lynes estate after his own land to the east of Martinsthorpe had been enclosed during Elizabeth's reign. He brought his son â John â and his young family with him. Nathaniel junior had been born sometime in the first decade of the century, and became steward on the death of his father in 1632. None of this

was new to me, but now I needed to focus on any information that would cast light on the Lynes family itself.

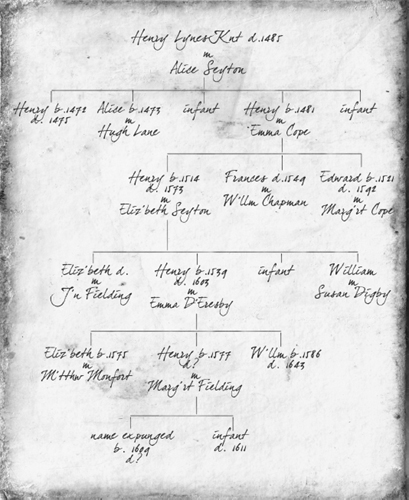

I leafed through the notebook, looking for significant references, my eyes already tired from deciphering my grandfather's space-saving script. He had made brief notes on what he discovered about them, followed by a sketchy family tree with bits missing. I squinted at it, his abbreviations not making the tiny print any easier to read.

It read like a social history. In footnotes, my grandfather had described how Henry Lynes had been knighted by Edward IV after the battle of Losecoat Field in 1470, which explained the advantageous marriages over the next generations to the progeny of local notable families, including â it would appear â our own. I idly wondered if that was why Grandpa had spent so much time researching them, then decided probably not. As much as I didn't believe in coincidence, our family name cropped up in the most peculiar places throughout the region and down the centuries, so that being linked to the Lynes at some point wasn't so surprising.

As interesting as the family tree was, it didn't take me any further than the parish records had done, except that it appeared that the Lynes family died out on the male side with the death of Henry Lynes in the 1640s. At least the relationship between Henry and Margaret was now clear, as was that between the two brothers, Henry and William â Henry being the elder by a number of years. But that was the sum of it.

I wriggled my toes in front of the fan-heater as they began to cook, and stretched my legs out either side of it, nudging the cat in the process, and elongating my arms as far as they would go without my ribs twingeing. I found myself able to stretch further each day, and each day I was reminded that Matthew should have removed the strapping for me, not some stranger in the local hospital. The thought of his closeness now all but a frail memory, my heart wrenched in loneliness. I tried not to think about what he might be doing, might be feeling. To endure the emptiness that swallowed all sensation, as it did for me, I found bad enough, but the thought that he might feel nothing at all was much, much worse. “Don't you

dare

,” I snarled out loud in an attempt to

forestall the temptation to wallow. “Stick to the script and get

on

with it â it won't solve itself.”

Tiberius blinked sleepily and stretched, his fuzzy tummy golden-olive; I stroked his soft fur and nibbled a bit of pork pie. I wasn't tired; the coffee still raced around my body like chipmunks in a cage, and there would be little point in trying to sleep.

I flipped over to the next page and stopped â hunger forgotten. Bingo! Grandpa had sketched six shields â family shields: five belonging to the landed families mentioned in the tree, and then the sixth â the Lynes shield. I recognized it at once: it had decorated the worn gold ring Matthew wore on his little finger, the one he had played with when deep in thought, the one he reluctantly let me see. I found what I had been looking for â a definitive link between Matthew Lynes of Maine, USA, and the Lynes of Rutland, England.

A blue shield: “Argent a tesse azure with three mullets d'or thereon.” And rearing above the silver inverted “V”, a gold lion, rampant.

Grandpa had used yellow ink to colour the three gold stars or mullets, one either side of the silver band, the third within, and it had faded a little over time, but the pattern remained quite clear. So why had Matthew claimed that his family originated in Scotland? Did he not know his family came from England â did he not question the emblem on the signet ring he wore? Did he not know, or didn't he want me to ask? And if not, why not?

OK, so I could think of three possibilities: first, that he didn't know his family's origins. Second, he knew where they came from but for some reason as yet unknown to me, felt ashamed of them. Third, he knew, but wanted to keep it secret.

The first was a possibility spoiled by the fact that he so

obviously lied. The second â perhaps he descended from an illegitimate branch of the family, and if so, so what? Who cared nowadays? It happened in the best families and I could name a dozen without thinking. The third â well, I already knew that he was hiding something from me and, given that he seemed to be a hundred years old or so, the last seemed the most likely explanation. How ridiculous! How totally fantastical. I paused in my soliloquy and waited for the impact of my supposition, but none came, and I wondered again if my sanity might be in doubt. I sucked my teeth, shrugged and continued my analysis.

Next question: If Matthew descended from the Rutland Lynes, from which branch did he spring? In the family tree Grandpa had traced, only two children were born to Henry and Margaret Lynes; of those, the youngest child had died â probably shortly after birth, since it had no recorded name. The older child's name had been expunged from the record â usually a sign of disfavour from the ruling regime, or possibly suicide, in which case there might not be records of the death. If the child had been male and had gone on to marry and have children of his own, his line would have carried his name, no matter what the ignominy of the father. The only other possibility might be that one of the Lynes daughters had carried the name with her, just as less-elevated families sometimes adopted a prestigious wife's name on marriage, either to continue it where there was no male heir, or for the sheer social advantage it would give the match. It was possible â but not likely. The Lynes were newly titled compared with the families they married into, and their name would not have carried the same kudos. No other children were recorded from male issue, although that didn't discount the possibility that the records were simply wrong or incomplete.

My grandfather must have found the information on the family from somewhere. He must have seen the original parish records. I had to see them for myself. I wanted to see what had been erased four centuries ago.