Death in Veracruz

Authors: Hector Camín

Copyright © 2015, Héctor Aguilar CamÃn

Original Title:

Morir en el Golfo

Translation Copyright, 2015 © Chandler Thompson

First English language Edition

Trade Paperback Original

License to reprint granted by Guillermo

Schavelzon Agenda Literaria

Tel (34) 932 011 310 ⢠Fax (34) 932 003 886 â¢

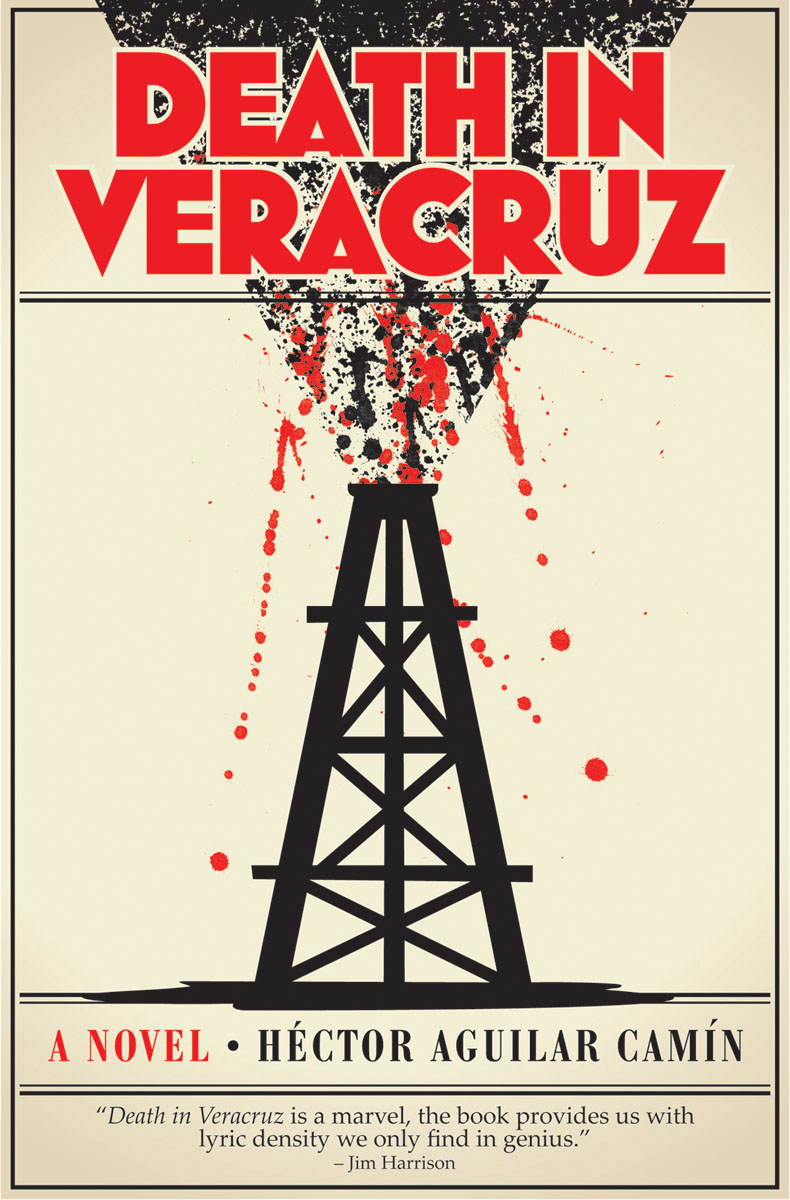

Cover Design: Dan Stiles

Interior Design: Darci Slaten

No part of this book may be excerpted or reprinted without the express written consent of the Publisher.

Contact: Permissions Dept., Schaffner Press, POB 41567,

Tucson, Az 85717

ISBN: 978-1-936182-92-3 (Paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-936182-93-0 (Mobipocket)

ISBN: 978-1-936182-94-7 (EPub)

ISBN; 978-1-936182-95-4 (Adobe)

For Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Information,

Contact the Publisher

Printed in the United States

Chapter 6: The Sacrificial Doe

Chapter 11: A Trumpet for Lacho

About the Author/Acknowledgments

THE ROJANO FILE

W

hat more is there to say about Rojano? It's a sob story better left untold. It consists of our two years as high school chums in Xalapa, then four as rivals at university in Mexico City where our shared obsession was Anabela GuillaumÃn. Rojano won. He left her, then he married her (I simply lost her.). He went in for Macazaga suits and political breakfasts at the Hilton. He joined the eternally governing PRI and became a minor functionary in the administration of López Arias in Veracruz. I went to work as a reporter on the police beat and took up the vice of journalism with all the trimmings. It was the 60s. We had come through the railroad strike and were headed towards the Tlatelolco massacre and the end of the Mexican miracle. Our lives as grownups were beginning.

After not seeing her for two years, on August 14, 1968, I ran into Anabela in the Arroyo Restaurant near the Olympic Village where she was working as a guide. She was as tall, slender and irresistible as ever with the same dazzling eyes. She owed their smoky green color and the surname of GuillaumÃn to the French occupiers who settled in Veracruz a century ago.

She skipped work, and we drank coffee all afternoon. She talked about Rojano, who was organizing student gangs and their leaders (“social services”) at the University of Veracruz and who, in drunken pre-dawn phone calls, accused her of slighting him. For dinner we had skewers of Chihuahua beef and beans cooked peasant-style with chiles at Pepe's on

Insurgentes.

She joked infectiously about working as a guide for peace. She spoke of her father's death a year earlier-her

mother died fifteen years ago-and of Rojano, his jealousy, his threats, the blow that almost tore her lip off one night, of how he had Mujica, a classmate she'd gone out with three times, beaten up. We drank vodka and danced until three in the morning at La Roca. She made fun of my qualms about being a reporter, and she talked about Rojano, the abortion he forced her to have, his demands, and his neglect. Drunk and talked out in the early morning hours, I lost her again, this time in the entrance to the Beverly Hotel, which reminded her, one more time, of Rojano.

They married two years later, the same month that Luis EcheverrÃa rose to power and the Institutional Revolutionary Party recognized Francisco Rojano Gutiérrez as undisputed leader of the CNOP, the National Confederation of People's Organizations, for the state of Veracruz.

I moved up from the police beat to city hall, then covered the airport for a few months. In early February 1971, I was just starting out on the agriculture beat when I ran into Rojano again in the main office of what was then the Department of Agrarian Affairs and Colonization. We hadn't seen each other for four years, since Christmas 1967 when we got into a fight at the Monteblanco Bar on Monterrey Street in the Roma District.

He had sprouted a mustache that hung like a horseshoe from his lips to his chin and was dressed in a double-breasted white suit, an orange shirt, and a tie of what were then called psychedelic colors. He had a fistful of papers in his hand and was in the process of authenticating a land deed. He was talking non-stop straight into the ear of a clerk.

“You've got to understand me,

paisano.”

He waved the sheaf of papers in the face of the hapless clerk and, by calling him

paisano,

appealed to the consideration one expatriate from Veracruz supposedly owed another.

As an ex-swimmer, he still had broad shoulders and a

flat torso. When he threw his arm over the clerk's shoulder, he engulfed the man in his enormous chest as if he were about to devour him. I tried not to be noticed, but Rojano caught a glimpse of me over the head of the beleaguered clerk.

“Is that you, brother?” His eyes lit up. The appeal of his vulgarity was impossible to define. He smiled and held up the papers. “I'm almost through here. Don't go away.”

I got what I'd come for and left without waiting through the door of the neighboring office. He ran after me and caught up with me in the parking lot. “You don't need to run, brother. I'm not a bill collector.” He grabbed my arm, gasping for breath.

He sucked air and loosened his tie. “I didn't greet you properly up there because I was working.” He moistened his lips, readjusted his tie. “I was dispatching my daily lawyer. I don't have to tell you the world is full of assholes, and, if you don't knock off at least one a day, then one of them will knock you off. Where are you going to eat?”

We ate at El Hórreo, a Spanish restaurant with a lively bar that overlooks the Alameda. Rojano ordered malt whiskeys and octopus sauteed in Rioja wine. He went on and on about politics in Veracruz, an endless parade of friends, enemies, crooks and assholes. He had detailed plans for his rise to governor and then to a federal cabinet post. First he'd become a mayor, then a state cabinet secretary, then a federal legislator; from there he'd go on to governor and federal cabinet secretary. He laid out a twenty-four-year career in politics free of setbacks or delays but with variations if necessary. If becoming mayor proved impossible, then he'd settle for a job in the state executive branch that would pave the way to the federal legislature. If that didn't work out, then president of the PRI or a position in a state-owned enterprise from which, with a bit of effort, he'd become a

cabinet minister. If the cabinet were out of reach, then.., and on and on.

We ordered cognac and coffee after dessert. He offered me a huge cigar from his coat pocket. On the band it said: Especially wrapped for

Francisco Rojano Gutiérrez, Atty.

Rojano had dropped out of third-year law (I got fed up after four), so I asked him. “When did you become a lawyer?”

“When we graduated together,” he replied smiling. “Don't tell me you can't remember. We did that thesis on mass politics and the Mexican state that was later plagiarized by Arnaldo Cordova. We even drew a mention from Flores Olea, don't you remember? Then you went into journalism and I took up government service. That's what got us where we are, brother, each serving the Republic in his own way. Let's toast to that, we're both doing fine.”

We matched each other drink for drink all afternoon, cognac and coffee until seven when we moved on to the Impala to hear Gloria Lasso sing. I woke up in the Silver Suites on VillalongÃn next to a woman I neither recognized nor remembered. In the bed next to mine Rojano lay snoring atop another woman. He had one sock on and the other off and a two-strand platinum bracelet on his wrist.

I changed to a newspaper that offered me the political beat and a daily news column called “Public Life” that became self-supporting in a matter of months. I set up a file system and stocked it with the exact sources and details of things hinted at over working breakfasts or dinners, in press offices, or in the columns of colleagues. In 1973, my column drew an honorable mention in the annual competition held by the Press Club of Mexico. The following year, I won the club's national prize for timely news coverage.

I stopped seeing Rojano, but I didn't lose sight of him. He returned to his post at the University of Veracruz in Xalapa,

then ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the state assembly from the district of Tuxpan. On February 4, 1972, Rojano was involved in a shootout in Juarez Park in Xalapa. The lone casualty was attributed to him, but though the victim was seriously injured (he didn't die), the charges against Rojano were thrown out in the course of a complex legal proceeding. In the year that followed, Rojano dropped out of local politics. He bought land in Chicontepec and got himself named an inspector for what was then the Rural Cooperative Credit Bank. In 1973, he resurfaced as a federal legislative hopeful in local newspaper columns and even in the column “Political Fronts” in

Excelsior.

The scheme failed although its real purpose was not to get elected but to make noise, to gain credibility within the party for achieving his real goal of becoming mayor of Chicontepec in elections to be held the following year. That didn't work out either, and he left the Rural Credit Bank in one of the anti-corruption purges the bank undergoes every couple of years. When the Veracruz state government changed hands in 1974, he returned to Xalapa as private secretary to the government secretary, a college friend who had previously been the private secretary of the incoming governor.

In 1975, I covered part of the PRI presidential campaign that every six years floods the country in a frenzy of ostentation and hope. The campaign of Treasury Secretary José López Portillo consisted, like all campaigns since Cárdenas in the 1930s, of a wide-ranging tour of the Republic, town by town, city by city with a retinue of local polÃticos, favorite sons, leaders, bosses, bureaucrats and orators in tow. This time the tour began in Querétaro, then moved on to the Pacific Coast. It rang in the New Year in the south with an enormous banquet at the base of the Chicoasén Dam in Chiapas (guests and food flown in by helicopter). The campaign proceeded through northern and central Mexico, then rolled through

the southeast and down the Gulf Coast before winding up in my home state of Veracruz, which we entered through Agua Dulce in March 1976.

The pressroom was barely set up at the Hotel Emporio in the port city of Veracruz when Rojano came looking for me. I had trouble recognizing him. The two-strand platinum bracelet was gone along with the horseshoe mustache and the psychedelic colors. His face and waistline were beginning to fill out, the pleats of his guayabera and the creases in his pants were painstakingly precise, and his brown moccasins were freshly shined.