Death of an Empire (56 page)

Read Death of an Empire Online

Authors: M. K. Hume

At Marathon, both Myrddion and Flavia left the galley, after a stern warning from the master that he must set sail quickly if the ship was to escape the tidal pull of Euboea, a huge land mass that ran parallel to the mainland. But the town of Marathon called to Myrddion with stories of Pheidippides who had run from the port to Athens to bring tidings of a great sea battle and, after imparting his news, had run back to Marathon without pause. Shortly after completing the return journey, he had died. The duty inherent in this tale of bravery and determination touched Myrddion’s nature, so he longed to see the landscape on which such epics of the human spirit were based.

On the other hand, Flavia longed to purchase something pretty to adorn her throat, so Myrddion offered her his protection. Rouged and perfumed, the lady avoided the piles of refuse, old fish heads, fish scales and rubbish that fouled the wharf. Marathon itself lay slightly inland on the higher ground and was too far to visit, so Myrddion swallowed his disappointment and took pleasure in watching Flavia as she haggled with street sellers who tried to tempt her with trinkets of base metal. Eventually, she found a dark cavern of a shop-front that promised Greek jewellery

within. Like a roe deer seeking sweet grass, she dived into its cool interior.

At first, Myrddion sat on his heels outside the unprepossessing premises but, out of sheer boredom, he eventually followed his lover into its dim recesses to remind her that they must hurry. He found Flavia poring over a strip of scarlet cloth on which lay bangles of heavy gold carved to resemble twining fish and a necklace that was a scaled serpent with a clasp shaped like a head swallowing its own tail. Its eyes were ruby chips and small, round emeralds decorated its spiny back.

‘Buy the damned thing if you like it, Flavia, but hurry! The galley will sail without us if you don’t make haste.’

‘A moment, Myrddion. The captain wouldn’t dare to sail without us. He has high hopes of a substantial sum at the end of the journey, if I’m satisfied with his services.’

Myrddion wandered around a whitewashed room that was far cleaner than its exterior suggested, except for spider’s webs that lurked in corners out of reach. The dim shelves concealed all kinds of merchandise in a wild tangle that seemed without logic or order. Painted pots in blood red, black and white jostled with weavings of warriors and maidens that had been crudely coloured with vegetable dyes. In one dusty corner, a collection of pottery and carved wooden gods looked down with impassive, blind eyes, including a tall staff shaped like a sea serpent with a carved frill and fins encircling its scaly throat. The wood was unfamiliar and as smooth as silk.

‘A fair piece of carving, master,’ a voice croaked at him from out of the gloom.

Myrddion spun round and the staff fell to the packed sod floor with a dull clatter. The face that loomed out of the darkness was old and seamed with wrinkles, and the eyes were white and blind with cataracts. At first, Myrddion thought that the wizened

creature was a man, but then it moved forward into a narrow strip of light from the doorway and revealed the dusty, bleached robes of a woman.

‘How much is the stave, mother?’ Myrddion asked, for in truth it attracted him strongly.

The old woman named a price that seemed fair, and although Myrddion knew he should haggle with her he was overly conscious of the swift passage of time. Searching through his satchel, he found the coin to pay what she asked and pressed them into her gnarled and twisted hands.

When their fingertips met, he felt an immediate jolt of precognition.

‘Ah, master, I’ll not need to read the portents for you. The Mother Serpent sits by your shoulder.’ She paused, and her nostrils twitched as if she smelt the air. ‘Beware of your woman, master. She may be rose-red, but like all pretty flowers her thorns are wicked and barbed. She will leave you weeping at the end of your journey.’

‘You are a terrible old woman,’ Flavia hissed from behind Myrddion’s shoulder. ‘How can you tell such lies?’

The old woman turned her milky irises towards the sound of Flavia’s voice and smiled, revealing browned and broken teeth.

‘Do I lie? You have learned to sell yourself to the highest bidder, but you still don’t know your worth, Woman of Straw. You might deck yourself in gems and drape yourself in gold, but until in your heart you believe what you say, you will wander without a home or a man you can call your own.’

Flavia scoffed, but Myrddion could detect a faint tremor in her voice. When the old woman turned her wizened face back towards Myrddion, her features fell into a kinder expression. Chilled, Myrddion wondered if he was staring at the most terrible aspect of the Mother, the Crone of Winter.

‘Remember, master, that you are like your father, but you don’t have to be him. The gods decreed at your birth that you have free will, so you need not follow the ancient and wicked patterns of your bloodline. See what is real, not what your heart longs to see. Choose wisely, or you will never know your home again and a great destiny will be lost for all time.’

‘Pay this charlatan so we can get out of this pesthole,’ Flavia ordered rudely, turning away with the serpent necklace round her throat. The old woman was affronted and made a strange sign with her fingers behind Flavia’s back.

‘I will take no coin for what I have seen. You should beware that the serpent doesn’t bite you when you least expect it, Woman of Straw. Beware of the eagle and the snake, woman, or you will die.’

With the old woman’s words and the cackle of her laughter ringing in his ears, Myrddion fled from the mean little establishment and found he was gasping in the open air. Flavia was already disappearing down the narrow, cobbled street towards the wharf, her speed fuelled by temper, so Myrddion was forced to run to catch up with her.

‘Now you know what it’s like when someone tells your future. How does it feel, healer?’

For several days, Myrddion and Flavia avoided each other on the galley. The lady chose to eat in her cabin and Myrddion was kept busy caring for an outbreak of dysentery that had struck down the sailors and the galley slaves. The crowded conditions in the double banks of oars were unhygienic and filthy, so Myrddion ordered the whole space to be sluiced with seawater and scrubbed clean. The same treatment was given to the malodorous quarters deep in the belly of the ship where the slaves were shackled and the sailors slept in filthy straw. Gradually, under the twin cures of cleanliness and purgatives, Myrddion controlled the vicious spread of the

stomach contagion, while he comforted himself with the knowledge that the disease wasn’t more serious.

When he was finally able to assure the captain that the dysentery had passed, the galley had moved past Scyros, Icus and Polyaegus and was beating out into open waters as they headed towards the great island of Lesbos and landfall at Eresus. The captain was more able than most of his ilk and chose to cross open water, steering by the angle of the sun by day and by the points of the stars at night.

The sea was wide and very dark, like purple wine, and so still that at noontide Myrddion imagined he could see the reflection of clouds in its deep waters. The sun never seemed to dim in a sky that was so bright and so blue that the colour hurt Myrddion’s eyes, while even the sunsets became glorious panoramas of gold, amber, scarlet and orange when the sea was set aflame. Myrddion felt a peace he had rarely known during his short life. For the first time in many months, he didn’t regret the impulse that had driven him to leave Segontium for these strange climes.

Inevitably, Flavia and Myrddion renewed their passion, although his lady seemed to seek him out for comfort and affirmation of her worth rather than out of an overriding lust. He wondered occasionally if she even cared for sexual congress, considering their coupling merely as proof of her power and her attractiveness. She also chose to talk in the long, dark reaches of the night when the fires of the spirit burn dimly, as if she needed someone in the world who would understand the motivation that drove her to trade her body for feelings of adequacy.

When she revealed to Myrddion that her father and brother had awakened her into womanhood, the healer was appalled and sickened. That Flavia was only ten at the time added to the betrayal that the child had endured.

‘It’s a pity that Aetius is dead. He should have been made to

suffer for what he did to you. From what you have told me, he died quickly and relatively painlessly. As for your brother Gaudentius, the Christian god has promised special punishment for such sins. I could almost wish myself to be Christian so I could pray for such justice.’

Flavia had wept and drawn comfort from Myrddion’s sympathy, but she shared nothing else of a private nature with him. She remained a tightly rolled scroll, since enemies might find tools with which to torture her if she revealed too much.

Lesbos, the famous island celebrated for its ancient society of women, hove into view like a large hollowed triangle of green valleys and soft hills. So many places had swum through Myrddion’s experiences that only the rudimentary maps that he continued to create could keep all the exotic places separate in his mind.

With fresh water and supplies of food on board after a brisk trading of Roman glass and pottery in exchange for amphorae of oil and wine,

Neptune’s Trident

skirted Lesbos and headed for the Propontis, the inland sea that led to Constantinople. The names now had a glister of Asian strangeness – Lemnos, Hephaestia and the famed River Scamander where it flowed into the salt waters. There, on the heights, Myrddion could see a Roman temple gleaming whitely in the sunshine, and pointed it out to Cadoc and Finn.

‘See how the temple glows in the sunlight as if it is lit from within. There, on the mount, is the famed city of Troy, which is also called Ilion by the local populace. It was there that Priam watched his son die in battle against Achilles, while his daughter, Cassandra, was thrown down from the walls because the Greeks feared her powers of prophecy. All for the sake of a beautiful woman called Helen!’

‘Nothing ever changes, master,’ Finn murmured, his eyes wide and glowing from the tales he had heard. ‘For love, we tear down any obstacles in our path.’

Cadoc opened his mouth to joke, but Finn stepped sharply on his foot. Myrddion understood. His assistants feared that, like the Trojans, he was being led to ruin by a beautiful, flawed woman.

Perhaps I am, Myrddion thought, but he was so lost in the web of Flavia’s complex personality that he no longer cared.

The Hellespontus was very narrow and the galley was now accompanied by a flotilla of ships of all kinds as they sailed through the channel towards the fabled city of Constantine. Once they had passed into the Propontis, they stayed within sight of land. The countryside was rich and adorned with groves of orange and lemon trees, huge swathes of olives on the higher ground and farms that clustered on the hills like neat, whitewashed boxes. Fishing boats strained under the weight of huge catches of fish and crustaceans, and everywhere the travellers looked they saw evidence of industry, wealth and rich trade heading for Constantinople from many far-flung nations.

Then, as dusk fell, lights filled the northern horizon ahead of them in a wide arc that almost dimmed the stars.

‘What lies ahead?’ a curious Myrddion asked the captain, as they lounged against the rail and enjoyed the evening air.

The man laughed through the bushy black beard that gave him a sinister air.

‘I thought you knew, master healer. You will soon gaze on the Golden Horn. Ahead lies the jewel of the east – the lights of Constantinople. Tomorrow, we dock in the city.’

‘Constantinople!’ Myrddion breathed, and his heart sang in wonderment that the whole, interminable journey was finally coming to an end.

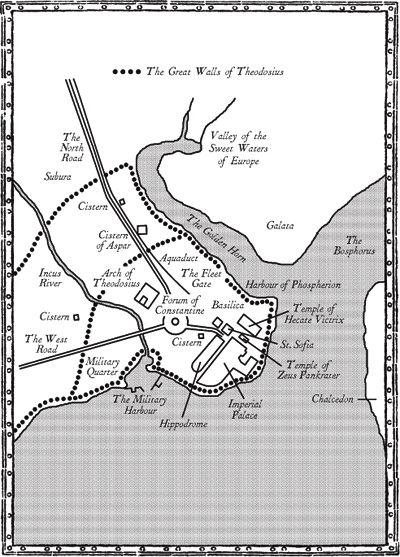

MYRDDION’S CHART OF CONSTANTINOPLE AND ITS ENVIRONS

THE GOLDEN HORN

The ship had sailed to the far end of the Propontis during the night, and a glistening summer sunrise rose over a city that spread across the narrow channel separating the Propontis from the huge inland sea called Pontus Euxinus. This narrow channel, wide and deep enough to permit the largest galleys to gain entrance to the vast inland sea, was called the Bosporus.

‘And that, young healer, is the Golden Horn,’ the captain announced expansively.

Myrddion saw the huge flotilla of ships of all shapes, sizes and points of origin as they rounded the peninsula of land that protruded out into the Propontis. Here, Constantinople was built. A large natural harbour lay around the point of a sickle-shaped channel of water that divided the city from its sisters, Chalcedon and Galata, across the Propontis and the Horn.

The early light revealed wonders. A vast military harbour with special gates to protect its entry hove into view, filled with fighting vessels drawn up in orderly rows. As far as Myrddion could tell, a massive wall protected the promontory, although marble buildings were visible behind it. Still, an impregnable fortress of stone faced blankly towards the Propontis, with the land rising in terraces above it. The galley rounded the point and the full wonders of

Constantinople appeared before them. Light glowed softly on roseate marble and kissed the roofs of the city with a glimmer of gold. The rising sun gilded the rigging of ships and the black shapes of galleys were rimed with light. Myrddion’s heart almost stopped with the beauty of the scene.