Decoded (4 page)

Authors: Jay-Z

Tags: #Rap & Hip Hop, #Rap musicians, #Rap musicians - United States, #Cultural Heritage, #Jay-Z, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Biography

LIFE STORIES TOLD THROUGH RAP

I was still rhyming, but now it took a backseat to hustling. It was all moving so fast, it was hard to make sense of it or see the big picture. Kids like me, the new hustlers, were going through something strange and twisted and had a crazy story to tell. And we needed to hear our story told back to us, so maybe we could start to understand it ourselves.

Hip-hop was starting to catch up. Fresh Gordon was one of Brooklyn’s biggest DJs. He was also seeing some action as a producer after he worked on Salt ’N’ Pepa’s big hit “Push It.” Like a lot of the DJs in the city, Gordy was doing mix tapes, and he had a relationship with my friend Jaz, so he invited us to come rhyme on a track he was recording with Big Daddy Kane. I laid my little verse down, but when I went home I couldn’t get Kane’s freestyle out of my head. I remember one punchline in Kane’s verse:

put a quarter in your ass / cuz you played yourself.

“Played yourself” wasn’t even a phrase back then. He made it up right there on that tape. Impressive. I probably wrote a million rhymes that night. That tape made it all around New York. It even traveled as far as Miami. (This was back when black radio had slogans that assured listeners they were “rap free,” so hip-hop moved on an underground railroad for real.) People were talking about the second kid on the tape, the MC before Kane—I was getting great feedback. I couldn’t believe people even noticed my verse, Kane’s was so sick.

Kane was Brooklyn’s superhero, and an all-time great, but among New York MCs there was no one like Rakim. In Rakim, we recognized a poet and deep thinker, someone who was getting closer to reflecting the truth of our lives in his tone and spirit. His flow was complex and his voice was ill; his vocal cords carried their own reverb, like he’d swallowed an amp. Back in 1986, when other MCs were still doing party rhymes, he was dead serious:

write a rhyme in graffiti and every show you see me in / deep concentration cause I’m no comedian.

He was approaching rap like literature, like art. And the songs still banged at parties.

Then the next wave crashed. Outside of New York, pioneers, like Ice-T in L.A. and Schoolly D in Philly, had rhymed about gang life for years. But then New York MCs started to push their own street stories. Boogie Down Productions came out with a hard but conscious street album,

Criminal Minded,

where KRS-One rhymed about catching a crack dealer with an automatic:

he reached for his pistol but it was just a waste / cuz my nine millimeter was up against his face.

Public Enemy came hard with songs about baseheads and black steel. These songs were exciting and violent, but they were also explicitly “conscious,” and anti-hustling. When NWA’s

Straight Outta Compton

claimed everything west of New Jersey, it was clear they were ushering in a new movement. Even though I liked the music, the rhymes seemed over the top. It wasn’t until I saw movies like

Boyz n the Hood

and

Menace II Society

that I could see how real crack culture had become all over the country. It makes sense, since it came from L.A., that the whole gangsta rap movement would be supported cinematically. But by the time Dre produced

The Chronic,

the music was the movie. That was the first West Coast album you could hear knocking all over Brooklyn. The stories in those songs—about gangbanging and partying and fucking and smoking weed—were real, or based on reality, and I loved it on a visceral level, but it wasn’t my story to tell.

IT’S LIKE THE BLUES, WE GON RIDE OUT ON THIS ONE

As an MC I still loved rhyming for the sake of rhyming, purely for the aesthetics of the rhyme itself—the challenge of moving around couplets and triplets, stacking double entendres, speed rapping. If it hadn’t been for hustling, I would’ve been working on being the best MC, technically, to ever touch a mic. But when I hit the streets for real, it altered my ambition. I finally had a story to tell. And I felt obligated, above all, to be honest about that experience.

That ambition defined my work from my first album on. Hip-hop had described poverty in the ghetto and painted pictures of violence and thug life, but I was interested in something a little different: the interior space of a young kid’s head, his psychology. Thirteen-year-old kids don’t wake up one day and say, “Okay, I just wanna sell drugs on my mother’s stoop, hustle on my block till I’m so hot niggas want to come look for me and start shooting out my mom’s living room windows.” Trust me, no one wakes up in the morning and wants to do that. To tell the story of the kid with the gun without telling the story of why he has it is to tell a kind of lie. To tell the story of the pain without telling the story of the rewards—the money, the girls, the excitement—is a different kind of evasion. To talk about killing niggas dead without talking about waking up in the middle of the night from a dream about the friend you watched die, or not getting to sleep in the first place because you’re so paranoid from the work you’re doing, is a lie so deep it’s criminal. I wanted to tell stories and boast, to entertain and to dazzle with creative rhymes, but every thing I said had to be rooted in the truth of that experience. I owed it to all the hustlers I met or grew up with who didn’t have a voice to tell their own stories—and to myself.

My life after childhood has two main stories: the story of the hustler and the story of the rapper, and the two overlap as much as they diverge. I was on the streets for more than half of my life from the time I was thirteen years old. People sometimes say that now I’m so far away from that life—now that I’ve got businesses and Grammys and magazine covers—that I have no right to rap about it. But how distant is the story of your own life ever going to be? The feelings I had during that part of my life were burned into me like a brand. It was life during wartime.

I lost people I loved, was betrayed by people I trusted, felt the breeze of bullets flying by my head. I saw crack addiction destroy families—it almost destroyed mine—but I sold it, too. I stood on cold corners far from home in the middle of the night serving crack fiends and then balled ridiculously in Vegas; I went dead broke and got hood rich on those streets. I hated it. I was addicted to it. It nearly killed me. But no matter what, it is the place where I learned not just who I was, but who we were, who all of us are. It was the site of my moral education, as strange as that may sound. It’s my core story and, just like you, just like anyone, that core story is the one that I have to tell. I was part of a generation of kids who saw something special about what it means to be human—something bloody and dramatic and scandalous that happened right here in America—and hip-hop was our way of reporting that story, telling it to ourselves and to the world. Of course, that story is still evolving—and my life is, too—so the way I tell it evolves and expands from album to album and song to song. But the story of the hustler was the story hip-hop was born to tell—not its only story, but the story that found its voice in the form and, in return, helped grow the form into an art.

Chuck D famously called hip-hop the CNN of the ghetto, and he was right, but hip-hop would be as boring as the news if all MCs did was report. Rap is also entertainment—and art. Going back to poetry for a minute: I love metaphors, and for me hustling is the ultimate metaphor for the basic human struggles: the struggle to survive and resist, the struggle to win and to make sense of it all.

This is why the hustler’s story—through hip-hop—has connected with a global audience. The deeper we get into those sidewalk cracks and into the mind of the young hustler trying to find his fortune there, the closer we get to the ultimate human story, the story of struggle, which is what defines us all.

J

ust Blaze was one of the house producers at Roc-A-Fella Records, the company I co-founded with Kareem Burke and Damon Dash. He’s a remarkable producer, one of the best of his generation. As much as anyone, he helped craft the Roc-A-Fella sound when the label was at its peak: manipulated soul samples and original drum tracks, punctuated by horn stabs or big organ chords. It was dramatic music: It had emotion and nostalgia and a street edge, but he combined those elements into something original. His best tracks were stories in themselves. With his genius for creating drama and story in music, it made sense that Just was also deep into video games. He’d written soundtracks for them. He played them. He collected them. He was even a character in one game. If he could’ve gotten bodily sucked into a video game, like that guy in

Tron

did, he would’ve been happy forever. I was recording

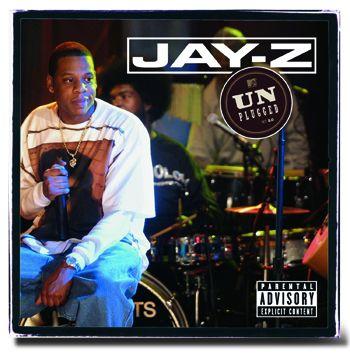

The Black Album

and wanted Just to give me one last song for the album, which was supposed to be my last, but he was distracted by his video-game work. He’d already given me one song, “December 4th,” for the album—but I was still looking for one more. He was coming up empty and we were running up against our deadlines for getting the album done and mastered.

At the same time, the promotion was already starting, which isn’t my favorite part of the process. I’m still a guarded person when I’m not in the booth or onstage or with my oldest friends, and I’m particularly wary of the media. Part of the pre-release promotion for the album was a listening session in the studio with a reporter from

The Village Voice,

a young writer named Elizabeth Mendez Berry. I was playing the album unfinished; I felt like it needed maybe two more songs to be complete. After we listened to the album the reporter came up to me and said the strangest thing: “You don’t feel funny?” I was like,

Huh?,

because I knew she meant funny as in weird, and I was thinking,

Actually, I feel real comfortable; this is one of the best albums of my career.

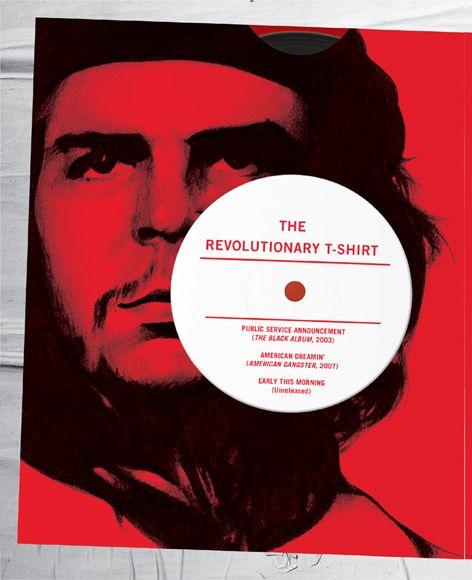

… But then she said it again: “You don’t feel funny? You’re wearing that Che T-shirt and you have—” she gestured dramatically at the chain around my neck. “I couldn’t even concentrate on the music,” she said. “All I could think of is that big chain bouncing off of Che’s forehead.” The chain was a Jesus piece—the Jesus piece that Biggie used to wear, in fact. It’s part of my ritual when I record an album: I wear the Jesus piece and let my hair grow till I’m done.