Delphi (14 page)

Authors: Michael Scott

It is testament to the increasing strength of Delphi in the Greek world, and indeed the wider world, at this time, as well as an example of the trend in the ancient literature to mark Delphi's credentials as increasingly antityrannical, that Delphi failed to treat well several powerful leaders who lavished its sanctuary with dedications when they came for oracular consultation.

39

The most famous examples are of Alyattes and his son Croesus, kings of Lydia. We have met this family before. Alyattes, king between 619 and 560

BC

, had attacked Miletus and burned down a temple of Athena. He had subsequently fallen ill and sent to Delphi for advice. The oracle had apparently refused to reply until the temple of Athena was restored, and when it was, Alyattes recovered, and subsequently sent a huge, silver mixing bowl on a welded iron base to Delphi (one of those Eastern dedications that collected in front of the new temple's eastern front). Croesus, on the other hand, was not so fortunate. It is his story of oracular consultation at Delphi that is perhaps Delphi's most famous, and that we touched on in an chapter about the workings of the Delphic oracle as the classic case of how

not

to ask your question at Delphi and the perils of misinterpreting the oracle's answers. It was Croesus's generation that the oracle had foreseen (or was later said to have foreseen) would bear the revenge for Gyges' slippery usurpation

of power (see previous chapters). Croesus, intent on gaining oracular approval for his upcoming military campaign is said to have first tested all the famous oracles around the Mediterranean to find out which one was the most accurate by sending messengers asking what he was doing one hundred days from the day they left Lydia (as Herodotus is keen to highlight, this was a very unusual form of question to an oracle). The oracle at Delphi was said to have answered correctly: Croesus was chopping up a tortoise and a lamb in a bronze cauldron with a bronze lid.

40

As a result, Croesus showered Delphi with dedications to sit resplendent in its newly articulated sanctuary. Different ancient sources claim he demanded contributions from individual Lydians, burned three thousand sacrificial victims along with encrusted gold and silver beads, casting the molten residue into 117 half-bricks (4 pure gold and the others white gold) to be surmounted by a lion statue of pure gold weighing ten talents. Nor did it stop there. Croesus also sent two extra-large mixing bowls, one of gold and one of silver, which would in Herodotus's day play a key role in Delphic temple ceremonies. He also sent four silver jars, two vessels (one of gold, one of silver), bowls of silver, a golden statue of a woman, and many other smaller dedications including the necklace and girdles of his queen.

41

All this, scholars have argued, demonstrated not merely a routine diplomatic gesture to a foreign god, but an offer of generosity the likes of which had never been seen in the Greek world.

42

It was all also a payment in advance for the answer to the key question Croesus had had in mind all along, the oracle's answer to which became famous in antiquity. Croesus asked “whether he should make an expedition against the Persians and whether he should make any further host of men his friends?”

43

Many ancient writers record the response “Croesus, having crossed the Halys, will destroy a great empire.” It is a reply that has become infamous for its ambiguity and misinterpretation, and subsequently for the danger inherent in consulting the Delphic oracle. Croesus of course did cross the river Halys, and he did destroy an empire: his own. Yet Croesus, interpreting it as meaning his enemy's empire, was so pleased by the response that he sent further gifts to Delphi (two gold staters for every

Delphic citizen), in return for which the Delphians gave him the right of promanteia (the right to skip the queue to consult the oracle),

ateleia

(the right to not pay the tax to consult the oracle), and

prohedria

(the right to front-row seats at the Pythian festival). Later, however, so upset was Croesus by what he saw as the oracle's failure to warn him that he asked permission of his now masterâthe Persian king, Cyrusâto take the chains of his captivity to Delphi and challenge the oracle to justify its conduct. The oracle is portrayed (in the later sources) as responding that Croesus was bound by destiny to pay for Gyges' actions, that he himself had misinterpreted the oracular response, and that, all in all, it was thanks to Apollo that he was even alive.

44

Yet the oracle at Delphi was not only standing up to some of the most powerful men at the borders of the Mediterranean world at this time, it was also playing hardball with those closer to home. One Spartan, Glaucus, who had denied that his friend had previously entrusted him with his money, was asked to swear an oath to that effect. Glaucus, according to Herodotus, consulted Delphi about whether it was defensible in the eyes of the gods to perjure oneself under oath if material gain resulted. The oracle replied resolutely in the negative and mishap dogged Glaucus's family for generations. The oracle could also play hardball with the Delphians themselves. One consultation story, reported in Herodotus and dating to c. 563â32

BC

, tells how Aesop (of Aesop's Fables fame), having insulted the Delphians for living off nothing except what Apollo gave them, was tricked by the Delphians into taking a sacred treasure away from the sanctuary.

45

Having set him up, the Delphians “discovered” his theft, convicted him, and had him thrown off the Hyampeia cliff high above Delphi. As a result, Delphi was smitten with plague and famine (we might think back again to the

Homeric Hymn to

Apollo

and Apollo's warning to his priests not to abuse their position). Consulting the oracle, the Delphians were told that finding a relative of Aesop's was key to their atonement, and they conducted such a search at every major Greek festival till they finally found a candidate.

Among these oracles responding to queries of plagues, famines, world domination, civic rebirth, perjury, and tortoise and lamb boiling

in bronze pots, Delphi also continued to answer queries about ritual practice, including the establishment of new rituals to different Greek divinities in various Greek cities.

46

Chief among these gods was Dionysus: in fact, there are more oracular responses recorded in the Delphic corpus relating to the worship of this god than any other. Dionysian cult practices may well already have been part of Delphic worship in this periodâindeed it may always have been. But it is only epigraphically and archaeologically attested, for certain, beginning in the fourth century

BC

, whence it would grow into an essential part of Delphic mythology, indeed one that would remain when many other aspects of Delphic business had been forgotten.

47

The oracle also continued, as in the previous century, to answer questions concerning the founding of new settlements. It was, after all, in the sixth century

BC

, that it became necessary to consult the oracle before a colonial adventure became a proverbial tale.

48

In the first half of the sixth century, Delphi continued to be consulted, for example, on the foundation of Heracleia Pontice by the Megarians and the Boeotians in the 560s

BC

and, in the same period, on the Athenian expedition to the Chersonesus (see

maps 1

,

2

).

49

More importantly, foundations with which it had been involved (or, as discussed in the last chapter, with which it later became preferable to different parties to cast the oracle as being involved in) in the previous century, in turn, went back to the sanctuary. Syracuse, for example, is argued to have constructed a treasury at Delphi in this period (its presence known thanks to surviving roofing fragments in bright red Sicilian clay).

50

In addition, the dedicatory record shows a swath of Western dedicators offering monumental structures at Delphi in this period, many of which do not seem to have had a direct connection to Delphi through a foundation oracle, but instead seem to represent the eagerness of these dedicators to ensure their presence at this increasingly important center of the ancient world. There are three treasury structures, for example, lined up opposite the western end of the new temple of Apollo, all leaning against the new perimeter wall of the sanctuary (structures C, D, and E in

fig. 3.2

). One of these (built c. 580

BC

) has been associated with

the Corcyrians because of its roofing style.

51

And two other treasury-like structures were dedicated in the southern part of the Apollo sanctuary behind the early Athenian treasury (see

plate 2

), which, again because of their roofing styles, have been associated with southern Italian (and probably Sybarite) dedicators.

52

All these structures seem to have taken advantage not only of the new perimeter wall, but also of new terracing walls within the sanctuary to claim positions of high visibility and dominate this new sanctuary space.

Also filling this new sanctuary space in the first half of the sixth century

BC

were a series of other treasury-like structures, whose function and dedicator we cannot claim with any certainty to know. One, perhaps two more structures, traditionally associated with the worship of Gaia but in reality uncertain, were constructed in this period. As well, a building, long labeled the Delphic city's bouleuterion but now the subject of disputed identification, was constructed near the Athenian treasury. We can also identify another series of monumental, and less monumental but incredibly ornate, dedications that graced the sanctuary at this time. The most ornate treasury yet, constructed c. 550

BC

, was dedicated by the Cnidians in Asia Minor (see

plate 2

). It was the first at Delphi to be built in marble and in the ionic style. No treasury-like structure has ever been found in their home city of Cnidos, but here at Delphi the Cnidians seem not only to have followed the trend for treasury dedication, but to have embellished it considerably. In contrast, the inhabitants of the island of Naxos in the Aegean chose to dedicate c. 570

BC

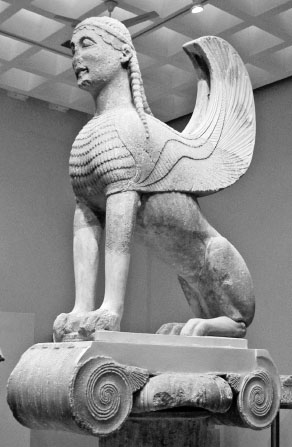

one of the sanctuary's most famous monuments, the Sphinx (see

plate 2

,

fig. 4.1

). This mythological creature with the body of a lion, the wings of a bird, and the face of a woman was something of a Naxian calling card in terms of artistic choice, as the Naxians had already dedicated a similar sculpture at the sanctuary of Apollo on Delos.

53

But it was also perfectly tuned to its location at Delphi: the sphinx's placement upon a tall column assured it was visible from all parts of the steep hillside.

In fact, we are only just scraping the surface of the ornate and expensive dedications that came from the eastern Mediterranean to Delphi in the first half of the sixth century

BC

. Herodotus tells us of the Egyptian courtesan Rhodopis who chose to dedicate a percentage of the wealth gained from her profession to Apollo at Delphi in the form of iron spits.

54

And in the 1930s a whole host of dedications was discovered that date from the eighth to the fifth centuries

BC

, and had at some point been intentionally buried, it seems, underneath the central pathway through the sanctuary. Among them was the fabulous life-size silver bull (

fig. 4.2

) now on display in the Delphi museum, which had originally been the gift of an Ionian dedicator. In addition, there were two chryselephantine (ivory and gold) statues (see

plate 5

), as well as another ivory statue from an earlier date, all also of Ionian provenance.

55

Figure 4.1

. The Naxian Sphinx, dedicated in the Apollo sanctuary at Delphi (Museum at Delphi).

Delphi, by the middle of the sixth century

BC

, had thus changed dramatically. In just fifty years, it had been the subject of major international conflict (the First Sacred War); had come under the auspices of the Amphictyony; had had its sacred space of Apollo officially articulated with perimeter walls, a temple of Apollo built, an increasing stream of monumental treasuries constructed within its new sanctuary, alongside a plethora of jaw-dropping gold and silver gifts from eastern rulers and a wealth of ornate dedications from around the eastern Mediterranean. Its oracle had been consulted by eastern kings and by the tyrants and reformers of mainland Greece; had laid down the law with oath-breakers and Delphian misbehavers; had helped guide the institution of rituals of divine worship; had continued to play a role in the ongoing processes of settlement foundation around the Mediterranean, and had enjoyed the fruits of the success of the developing communities it had been involved with founding in the previous century.

Delphi was, without a doubt, a major player in the ancient world by the mid-sixth century

BC

. But that should not be confused with its

having been a sanctuary for everyone. It was available only to those with vested interests in the Amphictyony during the conflict over Delphi, and to those who dedicated richly afterward. Much of mainland Greece did not choose to have a permanent presence within the sanctuary, and of northern Greece, there is almost no trace either in relation to the oracle or in terms of dedication. In contrast, this absence is countered by the overwhelming presence of many individuals and cities from the eastern and western boundaries of the Greek world. Delphi was international for sure, but, again, not open to everyone. Moreover, with its newfound success and importance came the difficult task of trying to negotiate a fast-changing and often cutthroat Greek world. The silver bull and chryselephantine statues discovered buried in the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi all showed signs of heavy fire damage. Delphi was soon to be rebornâyet againâthrough fiery destruction.