Delphi Complete Works of Oscar Wilde (Illustrated) (131 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Oscar Wilde (Illustrated) Online

Authors: OSCAR WILDE

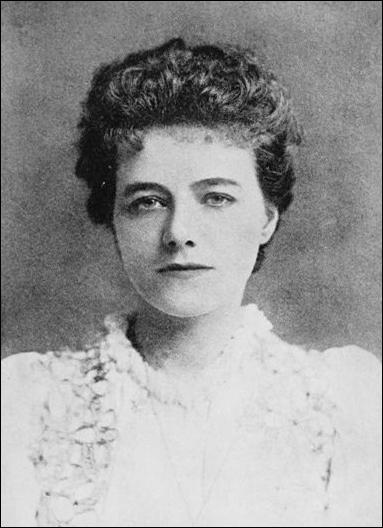

In London, Wilde had been introduced in 1881 to Constance Lloyd, daughter of Horace Lloyd, a wealthy Queen’s Counsel. She happened to be visiting Dublin in 1884, when Wilde was lecturing at the Gaiety Theatre. He proposed to her and they married on 29 May 1884 at the Anglican St. James Church in Paddington in London.

Constance Wilde (1859-1898), born Constance Mary Lloyd, was the wife of Oscar Wilde and the mother of his two sons, Cyril and Vyvyan.

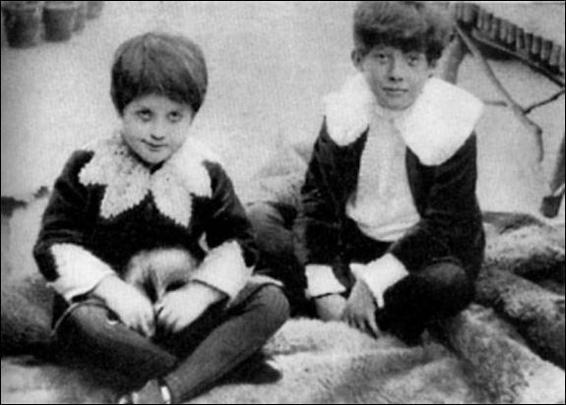

Wilde’s sons

This short story was first published in

Blackwood’s Magazine

in 1889. It was later added to the collection

Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and Other Stories

, though it does not appear in early editions.

The story narrates an attempt to uncover the identity of Mr W.H., the enigmatic dedicatee of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. It is based on a theory, originated by Thomas Tyrwhitt, that the Sonnets were addressed to one Willie Hughes, portrayed in the story as a boy actor who specialised in playing women in Shakespeare’s company. This theory depends on the assumption that the dedicatee is also the ‘Fair Youth’ who is the subject of most of the poems. The only evidence for this theory is a number of sonnets (such as Sonnet 20) that make puns on the words ‘Will’ and ‘Hues.’

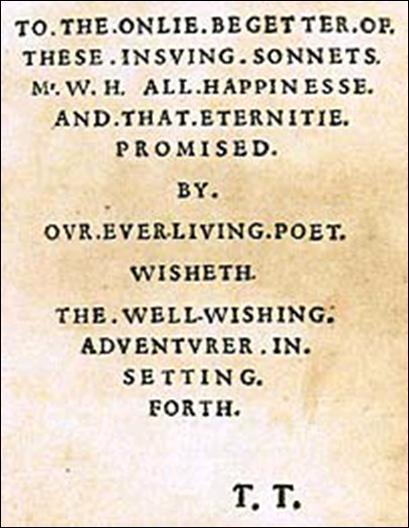

The

first edition of Shakespeare’s sonnets, with the dedication to the mysterious T.T.

I

I had been dining with Erskine in his pretty little house in Birdcage Walk, and we were sitting in the library over our coffee and cigarettes, when the question of literary forgeries happened to turn up in conversation. I cannot at present remember how it was that we struck upon this somewhat curious topic, as it was at that time, but I know that we had a long discussion about Macpherson, Ireland, and Chatterton, and that with regard to the last I insisted that his so-called forgeries were merely the result of an artistic desire for perfect representation; that we had no right to quarrel with an artist for the conditions under which he chooses to present his work; and that all Art being to a certain degree a mode of acting, an attempt to realise one’s own personality on some imaginative plane out of reach of the trammelling accidents and limitations of real life, to censure an artist for a forgery was to confuse an ethical with an æsthetical problem.

Erskine, who was a good deal older than I was, and had been listening to me with the amused deference of a man of forty, suddenly put his hand upon my shoulder and said to me “What would you say about a young man who had a strange theory about a certain work of art, believed in his theory, and committed a forgery in order to prove it?”

“Ah! that is quite a different matter,” I answered.

Erskine remained silent for a few moments, looking at the thin grey threads of smoke that were rising from his cigarette. “Yes,” he said, after a pause, “quite different.”

There was something in the tone of his voice, a slight touch of bitterness perhaps, that excited my curiosity. “Did you ever know anybody who did that?” I cried.

“Yes,” he answered, throwing his cigarette into the fire, – “a great friend of mine, Cyril Graham. He was very fascinating, and very foolish, and very heartless. However, he left me the only legacy I ever received in my life.”

“What was that?” I exclaimed. Erskine rose from his seat, and going over to a tall inlaid cabinet that stood between the two windows, unlocked it, and came back to where I was sitting, holding in his hand a small panel picture set in an old and somewhat tarnished Elizabethan frame.

It was a full-length portrait of a young man in late sixteenth-century costume, standing by a table, with his right hand resting on an open book. He seemed about seventeen years of age, and was of quite extraordinary personal beauty, though evidently somewhat effeminate. Indeed, had it not been for the dress and the closely cropped hair, one would have said that the face, with its dreamy wistful eyes, and its delicate scarlet lips, was the face of a girl. In manner, and especially in the treatment of the hands, the picture reminded one of Francois Clouet’s later work. The black velvet doublet with its fantastically gilded points, and the peacock-blue background against which it showed up so pleasantly, and from which it gained such luminous value of colour, were quite in Clouet’s style; and the two masks of Tragedy and Comedy that hung somewhat formally from the marble pedestal had that hard severity of touch – so different from the facile grace of the Italians – which even at the Court of France the great Flemish master never completely lost, and which in itself has always been a characteristic of the northern temper.

“It is a charming thing,” I cried; “but who is this wonderful young man, whose beauty Art has so happily preserved for us?”

“This is the portrait of Mr W H,” said Erskine, with a sad smile. It might have been a chance effect of light, but it seemed to me that his eyes were quite bright with tears.

“Mr W H!” I exclaimed; “who was Mr W H?”

“Don’t you remember?” he answered; “look at the book on which his hand is resting.”

“I see there is some writing there, but I cannot make it out,” I replied.

“Take this magnifying-glass and try,” said Erskine, with the same sad smile still playing about his mouth.

I took the glass, and moving the lamp a little nearer, I began to spell out the crabbed sixteenth-century handwriting. “To the onlie begetter of these insuing sonnets.” . . . “Good heavens!” I cried, “is this Shakespeare’s Mr W H?”

“Cyril Graham used to say so,” muttered Erskine.

“But it is not a bit like Lord Pembroke,” I answered. “I know the Penshurst portraits very well. I was staying near there a few weeks ago.”

“Do you really believe then that the Sonnets are addressed to Lord Pembroke?” he asked.

“I am sure of it,” I answered. “Pembroke, Shakespeare, and Mrs Mary Fitton are the three personages of the Sonnets; there is no doubt at all about it.”

“Well, I agree with you,” said Erskine, “but I did not always think so. I used to believe well, I suppose I used to believe in Cyril Graham and his theory.”

“And what was that?” I asked, looking at the wonderful portrait, which had already begun to have a strange fascination for me.

“It is a long story,” said Erskine, taking the picture away from me rather abruptly I thought at the time – “a very long story; but if you care to hear it, I will tell it to you.”

“I love theories about the Sonnets,” I cried; “but I don’t think I am likely to be converted to any new idea. The matter has ceased to be a mystery to any one. Indeed, I wonder that it ever was a mystery.”

“As I don’t believe in the theory, I am not likely to convert you to it,” said Erskine, laughing; “but it may interest you.”

“Tell it to me, of course,” I answered. “If it is half as delightful as the picture, I shall be more than satisfied.”

“Well,” said Erskine, lighting a cigarette, “I must begin by telling you about Cyril Graham himself. He and I were at the same house at Eton. I was a year or two older than he was, but we were immense friends, and did all our work and all our play together. There was, of course, a good deal more play than work, but I cannot say that I am sorry for that. It is always an advantage not to have received a sound commercial education, and what I learned in the playing fields at Eton has been quite as useful to me as anything I was taught at Cambridge. I should tell you that Cyril’s father and mother were both dead. They had been drowned in a horrible yachting accident off the Isle of Wight. His father had been in the diplomatic service, and had married a daughter, the only daughter, in fact, of old Lord Crediton, who became Cyril’s guardian after the death of his parents. I don’t think that Lord Crediton cared very much for Cyril. He had never really forgiven his daughter for marrying a man who had not a title. He was an extraordinary old aristocrat, who swore like a coster-monger, and had the manners of a farmer. I remember seeing him once on Speech-day. He growled at me, gave me a sovereign, and told me not to grow up ‘a damned Radical’ like my father. Cyril had very little affection for him, and was only too glad to spend most of his holidays with us in Scotland. They never really got on together at all. Cyril thought him a bear, and he thought Cyril effeminate. He was effeminate, I suppose, in some things, though he was a very good rider and a capital fencer. In fact he got the foils before he left Eton. But he was very languid in his manner, and not a little vain of his good looks, and had a strong objection to football. The two things that really gave him pleasure were poetry and acting. At Eton he was always dressing up and reciting Shakespeare, and when we went up to Trinity he became a member of the ADC his first term. I remember I was always very jealous of his acting. I was absurdly devoted to him; I suppose because we were so different in some things. I was a rather awkward, weakly lad, with huge feet, and horribly freckled. Freckles run in Scotch families just as gout does in English families. Cyril used to say that of the two he preferred the gout; but he always set an absurdly high value on personal appearance, and once read a paper before our debating society to prove that it was better to be good-looking than to be good. He certainly was wonderfully handsome. People who did not like him, Philistines and college tutors, and young men reading for the Church, used to say that he was merely pretty; but there was a great deal more in his face than mere prettiness. I think he was the most splendid creature I ever saw, and nothing could exceed the grace of his movements, the charm of his manner. He fascinated everybody who was worth fascinating, and a great many people who were not. He was often wilful and petulant, and I used to think him dreadfully insincere. It was due, I think, chiefly to his inordinate desire to please. Poor Cyril! I told him once that he was contented with very cheap triumphs, but he only laughed. He was horribly spoiled. All charming people, I fancy, are spoiled. It is the secret of their attraction.

“However, I must tell you about Cyril’s acting. You know that no actresses are allowed to play at the ADC. At least they were not in my time. I don’t know how it is now. Well, of course Cyril was always cast for the girls’ parts, and when

As You Like It

was produced he played Rosalind. It was a marvellous performance. In fact, Cyril Graham was the only perfect Rosalind I have ever seen. It would be impossible to describe to you the beauty, the delicacy, the refinement of the whole thing. It made an immense sensation, and the horrid little theatre, as it was then, was crowded every night. Even when I read the play now I can’t help thinking of Cyril. It might have been written for him. The next term he took his degree, and came to London to read for the diplomatic. But he never did any work. He spent his days in reading Shakespeare’s Sonnets, and his evenings at the theatre. He was, of course, wild to go on the stage. It was all that I and Lord Crediton could do to prevent him. Perhaps if he had gone on the stage he would be alive now. It is always a silly thing to give advice, but to give good advice is absolutely fatal. I hope you will never fall into that error. If you do, you will be sorry for it.

“Well, to come to the real point of the story, one day I got a letter from Cyril asking me to come round to his rooms that evening. He had charming chambers in Piccadilly overlooking the Green Park, and as I used to go to see hint every day, I was rather surprised at his taking the trouble to write. Of course I went, and when I arrived I found him in a state of great excitement. He told me that he had at last discovered the true secret of Shakespeare’s Sonnets; that all the scholars and critics had been entirely on the wrong tack; and that he was the first who, working purely by internal evidence, had found out who Mr W H really was. He was perfectly wild with delight, and for a long time would not tell me his theory. Finally, he produced a bundle of notes, took his copy of the Sonnets off the mantelpiece, and sat down and gave me a long lecture on the whole subject.

“He began by pointing out that the young man to whom Shakespeare addressed these strangely passionate poems must have been somebody who was a really vital factor in the development of his dramatic art, and that this could not be said either of Lord Pembroke or Lord Southampton. Indeed, whoever he was, he could not have been anybody of high birth, as was shown very clearly by the 25th Sonnet

, in which Shakespeare contrasts himself with those who are ‘great princes’ favourites’; says quite frankly –

Let those who are in favour with their stars

Of public honour and proud titles boast,

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars,

Unlook’d for Joy in that I honour most;

and ends the sonnet by congratulating himself on the mean state of him he so adored:

Then happy I, that loved and am beloved

Where I may not remove nor be removed.

This sonnet Cyril declared would be quite unintelligible if we fancied that it was addressed to either the Earl of Pembroke or the Earl of Southampton, both of whom were men of the highest position in England and fully entitled to be called ‘great princes’; and he in corroboration of his view read me Sonnets CXXIV

and CXXV

, in which Shakespeare tells us that his love is not ‘the child of state’, that it ‘suffers not in smiling pomp’, but is ‘builded far from accident’. I listened with a good deal of interest, for I don’t think the point had ever been made before; but what followed was still more curious, and seemed to me at the time to entirely dispose of Pembroke’s claim. We know from Meres that the Sonnets had been written before 1598, and Sonnet CIV

informs us that Shakespeare’s friendship for Mr W H had been already in existence for three years. Now Lord Pembroke, who was born in 1580, did not come to London till he was eighteen years of age, that is to say till 1598, and Shakespeare’s acquaintance with Mr W H must have begun in 1594, or at the latest in 1595. Shakespeare, accordingly, could not have known Lord Pembroke till after the Sonnets had been written.

“Cyril pointed out also that Pembroke’s father did not die till 1601; whereas it was evident from the

line

,

You had a father, let your son say so,

that the father of Mr W H was dead in 1598. Besides, it was absurd to imagine that any publisher of the time, and the preface is from the publisher’s hand, would have ventured to address William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, as Mr W H; the case of Lord Buckhurst being spoken of as Mr Sackville being not really a parallel instance, as Lord Buckhurst was not a peer, but merely the younger son of a peer, with a courtesy title, and the passage in

England’s Parnassus

where he is so spoken of, is not a formal and stately dedication, but simply a casual allusion. So far for Lord Pembroke, whose supposed claims Cyril easily demolished while I sat by in wonder. With Lord Southampton Cyril had even less difficulty. Southampton became at a very early age the lover of Elizabeth Vernon, so he needed no entreaties to marry; he was not beautiful; he did not resemble his mother, as Mr W H did

–