Delphi Complete Works of Robert Burns (Illustrated) (Delphi Poets Series) (157 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Robert Burns (Illustrated) (Delphi Poets Series) Online

Authors: Robert Burns

CXCIII. — TO MR. JAMES JOHNSON.

CXCIV. — TO MR. PETER MILLER, JUN., OF DALSWINION.

131

CXCVII. — TO MRS. DUNLOP, IN LONDON.

CXVIII. — TO THE HON, THE PROVOST, ETC., OF DUMFRIES.

CCV. — TO MR. JAMES BURNESS, WRITER, MONTROSE.

CCVI. — TO HIS FATHER-IN-LAW, JAMES ARMOUR, MASON, MAUCHLINE.

138

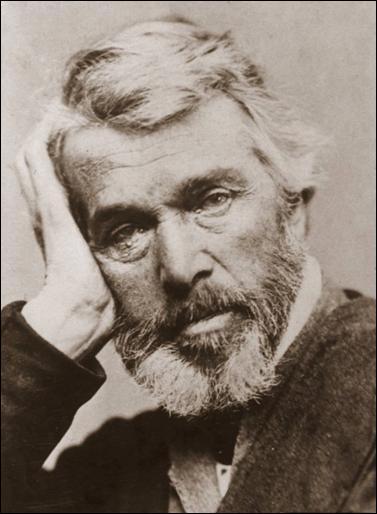

Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) was a Scottish philosopher, satirical writer, essayist and historian during the Victorian era, rising to became a controversial social commentator of his time. Coming from a strict Calvinist family, Carlyle was expected to become a preacher by his parents, but while at the University of Edinburgh he lost his Christian faith. Calvinist values, however, remained with him throughout his life. His combination of a religious temperament with loss of faith in traditional Christianity, made Carlyle’s work appealing to many Victorians who were grappling with scientific and political changes that threatened the traditional social order. He offered an incisive style to his social and political criticism and a complex literary style to works such as

The French Revolution: A History

(1837), which later served as a source for Charles Dickens’

A Tale of Two Cities

.

Carlyle developed influential ideas of Socialism and his belief in the importance of heroic leadership, as argued in his monumental work

On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History

(1841), in which he compared a wide range of different types of heroes, including Oliver Cromwell, Napoleon, William Shakespeare and, of course, his beloved fellow Scot Robert Burns.

In his mature years, Carlyle published the following detailed and affectionate biography of Robert Burns in 1859.

Thomas Carlyle

Robert Burns, the national bard of Scotland, was born on the 25th of January,

These worthy individuals labored diligently for the support of an increasing family; nor, in the midst of harassing struggles did they neglect the mental improvement of their offspring; a characteristic of Scottish parents, even under the most depressing circumstances. In his sixth year, Robert was put under the tuition of one Campbell, and subsequently under Mr. John Murdoch, a very faithful and pains-taking teacher. With this individual he remained for a few years, and was accurately instructed in the first principles of composition. The poet and his brother Gilbert were the aptest pupils in the school, and were generally at the head of the class. Mr. Murdoch, in afterwards recording the impressions which the two brothers made on him, says: “Gilbert always appeared to me to possess a more lively imagination, and to be more of the wit, than Robert. I attempted to teach them a little church music. Here they were left far behind by all the rest of the school. Robert’s ear, in particular, was remarkably dull, and his voice untunable. It was long before I could get them to distinguish one tune from another. Robert’s countenance was generally grave, and expressive of a serious, contemplative, and thoughtful mind. Gilbert’s face said,

Mirth, with thee I mean to live

; and certainly, if any person who knew the two boys had been asked which of them was the most likely to court the muses, he would never have guessed that

Robert

had a propensity of that kind.”

Besides the tuition of Mr. Murdoch, Burns received instructions from his father in writing and arithmetic. Under their joint care, he made rapid progress, and was remarkable for the ease with which he committed devotional poetry to memory. The following extract from his letter to Dr. Moore, in 1787, is interesting, from the light which it throws upon his progress as a scholar, and on the formation of his character as a poet:— “At those years,” says he, “I was by no means a favorite with anybody. I was a good deal noted for a retentive memory, a stubborn, sturdy something in my disposition, and an enthusiastic idiot piety. I say idiot piety, because I was then but a child. Though it cost the schoolmaster some thrashings, I made an excellent scholar; and by the time I was ten or eleven years of age, I was a critic in substantives, verbs, and particles. In my infant and boyish days, too, I owed much to an old woman who resided in the family, remarkable for her ignorance, credulity, and superstition. She had, I suppose, the largest collection in the country, of tales and songs, concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantrips, giants, enchanted towers, dragons, and other trumpery. This cultivated the latent seeds of poetry; but had so strong an effect upon my imagination, that to this hour, in my nocturnal rambles, I sometimes keep a sharp look-out in suspicious places; and though nobody can be more skeptical than I am in such matters, yet it often takes an effort of philosophy to shake off these idle terrors. The earliest composition that I recollect taking pleasure in, was,

The Vision of Mirza

, and a hymn of Addison’s, beginning, “

How are thy servants blest, O Lord!

” I particularly remember one-half stanza, which was music to my boyish ear:

“For though on dreadful whirls we hung

High on the broken wave.”

I met with these pieces in

Mason’s English Collection

, one of my school-books. The first two books I ever read in private, and which gave me more pleasure than any two books I ever read since, were,

The Life of Hannibal

, and

The History of Sir William Wallace

. Hannibal gave my young ideas such a turn, that I used to strut in raptures up and down after the recruiting drum and bagpipe, and wish myself tall enough to be a soldier; while the story of Wallace poured a tide of Scottish prejudice into my veins, which will boil along there till the flood-gates of life shut in eternal rest.”

Mr. Murdoch’s removal from Mount Oliphant deprived Burns of his instructions; but they were still continued by the father of the bard. About the age of fourteen, he was sent to school every alternate week for the improvement of his writing. In the mean while, he was busily employed upon the operations of the farm; and, at the age of fifteen, was considered as the principal laborer upon it. About a year after this he gained three weeks of respite, which he spent with his old tutor, Murdoch, at Ayr, in revising the English grammar, and in studying the French language, in which he made uncommon progress. Ere his sixteenth year elapsed, he had considerably extended his reading. The vicinity of Mount Oliphant to Ayr afforded him facilities for gratifying what had now become a passion. Among the books which he had perused were some plays of Shakspeare, Pope, the works of Allan Ramsay, and a collection of songs, which constituted his

vade mecum

. “I pored over them,” says he, “driving my cart or walking to labor, song by song, verse by verse, carefully noticing the true, tender or sublime, from affectation and fustian.” So early did he evince his attachment to the lyric muse, in which he was destined to surpass all who have gone before or succeeded him.

At this period the family removed to Lochlea, in the parish of Tarbolton. Some time before, however, he had made his first attempt in poetry. It was a song addressed to a rural beauty, about his own age, and though possessing no great merit as a whole, it contains some lines and ideas which would have done honor to him at any age. After the removal to Lochlea, his literary zeal slackened, for he was thus cut off from those acquaintances whose conversation stimulated his powers, and whose kindness supplied him with books. For about three years after this period, he was busily employed upon the farm, but at intervals he paid his addresses to the poetic muse, and with no common success. The summer of his nineteenth year was spent in the study of mensuration, surveying, etc., at a small sea-port town, a good distance from home. He returned to his father’s considerably improved. “My reading,” says he, “was enlarged with the very important addition of Thomson’s and Shenstone’s works. I had seen human nature in a new phasis; and I engaged several of my school-fellows to keep up a literary correspondence with me. This improved me in composition. I had met with a collection of letters by the wits of Queen Anne’s reign, and I pored over them most devoutly; I kept copies of any of my own letters that pleased me, and a comparison between them and the composition of most of my correspondents flattered my vanity. I carried this whim so far, that though I had not three farthings’ worth of business in the world, yet almost every post brought me as many letters as if I had been a broad, plodding son of day-book and ledger.”

His mind, peculiarly susceptible of tender impressions, was continually the slave of some rustic charmer. In the “heat and whirlwind of his love,” he generally found relief in poetry, by which, as by a safety-valve, his turbulent passions were allowed to have vent. He formed the resolution of entering the matrimonial state; but his circumscribed means of subsistence as a farmer preventing his taking that step, he resolved on becoming a flax-dresser, for which purpose he removed to the town of Irvine, in 1781. The speculation turned out unsuccessful; for the shop, catching fire, was burnt, and the poet returned to his father without a sixpence. During his stay at Irvine he had met with Ferguson’s poems. This circumstance was of some importance to Burns, for it roused his poetic powers from the torpor into which they had fallen, and in a great measure finally determined the

Scottish

character of his poetry. He here also contracted some friendships, which he himself says did him mischief; and, by his brother Gilbert’s account, from this date there was a serious change in his conduct. The venerable and excellent parent of the poet died soon after his son’s return. The support of the family now devolving upon Burns, in conjunction with his brother he took a sub-lease of the farm of Mossgiel, in the parish of Mauchline. The four years which he resided upon this farm were the most important of his life. It was here he felt that nature had designed him for a poet; and here, accordingly, his genius began to develop its energies in those strains which will make his name familiar to all future times, the admiration of every civilized country, and the glory and boast of his own.

The vigor of Burns’s understanding, and the keenness of his wit, as displayed more particularly at masonic meetings and debating clubs, of which he formed one at Mauchline, began to spread his fame as a man of uncommon endowments. He now could number as his acquaintance several clergymen, and also some gentlemen of substance; amongst whom was Mr. Gavin Hamilton, writer in Mauchline, one of his earliest patrons. One circumstance more than any other contributed to increase his notoriety. “Polemical divinity,” says he to Dr. Moore in 1787, “about this time was putting the country half mad; and I, ambitious of shining in conversation-parties on Sundays, at funerals, etc., used to puzzle Calvinism with so much heat and indiscretion, that I raised a hue-and-cry of heresy against me, which has not ceased to this hour.” The farm which he possessed belonged to the Earl of Loudon, but the brothers held it in sub-lease from Mr. Hamilton. This gentleman was at open feud with one of the ministers of Mauchline, who was a rigid Calvinist. Mr. Hamilton maintained opposite tenets; and it is not matter of surprise that the young farmer should have espoused his cause, and brought all the resources of his genius to bear upon it. The result was

The Holy Fair

,

The Ordination

,

Holy Willie’s Prayer

, and other satires, as much distinguished for their coarse severity and bitterness, as for their genius.

The applause which greeted these pieces emboldened the poet, and encouraged him to proceed. In his life, by his brother Gilbert, a very interesting account is given of the occasions which gave rise to the poems, and the chronological order in which they were produced. The exquisite pathos and humor, the strong manly sense, the masterly command of felicitous language, the graphic power of delineating scenery, manners, and incidents, which appear so conspicuously in his various poems, could not fail to call forth the admiration of those who were favored with a perusal of them. But the clouds of misfortune were gathering darkly above the head of him who was thus giving delight to a large and widening circle of friends. The farm of Mossgiel proved a losing concern; and an amour with Miss Jane Armour, afterwards Mrs. Burns, had assumed so serious an aspect, that he at first resolved to fly from the scene of his disgrace and misery. One trait of his character, however, must be mentioned. Before taking any steps for his departure, he met Miss Armour by appointment, and gave into her hands a written acknowledgment of marriage, which, when produced by a person in her situation, is, according to the Scots’ law, to be accepted as legal evidence of an

irregular

marriage having really taken place. This the lady burned, at the persuasion of her father, who was adverse to a marriage; and Burns, thus wounded in the two most powerful feelings of his mind, his love and pride, was driven almost to insanity. Jamaica was his destination; but as he did not possess the money necessary to defray the expense of his passage out, he resolved to publish some of his best poems, in order to raise the requisite sum. These views were warmly promoted by some of his more opulent friends; and a sufficiency of subscribers having been procured, one of the finest volumes of poetry that ever appeared in the world issued from the provincial press of Kilmarnock.

It is hardly possible to imagine with what eager admiration and delight they were every where received. They possessed in an eminent degree all those qualities which invariably contribute to render any literary work quickly and permanently popular. They were written in a phraseology of which all the powers were universally felt, and which being at once antique, familiar, and now rarely written, was therefore fitted to serve all the dignified and picturesque uses of poetry, without making it unintelligible. The imagery and the sentiments were at once natural, impressive, and interesting. Those topics of satire and scandal in which the rustic delights; that humorous imitation of character, and that witty association of ideas, familiar and striking, yet not naturally allied to one another, which has force to shake his sides with laughter; those fancies of superstition, at which one still wonders and trembles; those affecting sentiments and images of true religion, which are at once dear and awful to the heart; were all represented by Burns with the magical power of true poetry. Old and young, high and low, grave and gay, learned and ignorant, all were alike surprised and transported.

In the mean time, a few copies of these fascinating poems found their way to Edinburgh, and having been read to Dr. Blacklock, obtained his warmest approbation; and he advised the author to repair to Edinburgh. Burns lost no time in complying with this request; and accordingly, towards the end of the year 1786, he set out for the capitol, where he was received by Dr. Blacklock with the most flattering kindness, and introduced to every person of taste among that excellent man’s friends. Multitudes now vied with each other in patronizing the rustic poet. Those who possessed at once true taste and ardent philanthropy were soon united in his praise; those who were disposed to favor any good thing belonging to Scotland, purely because it was Scottish, gladly joined the cry; while those who had hearts and understandings to be charmed without knowing why, when they saw their native customs, manners, and language, made the subjects and the materials of poesy, could not suppress that impulse of feeling which struggled to declare itself in favor of Burns.