Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1321 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

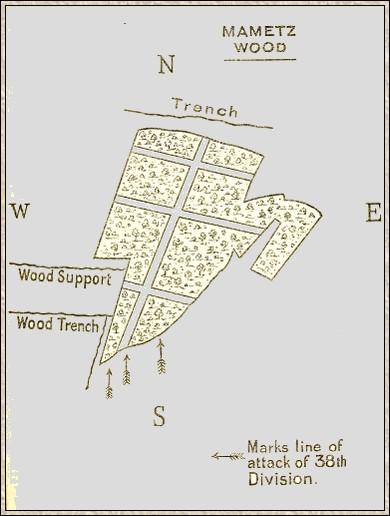

At six in the morning of July 8 the undefeatable Seventeenth Division was again hard at work encompassing the downfall of its old opponents in Quadrangle Support. Since it could not be approached above ground, it was planned that two brigades, the 51st and the 50th, should endeavour to bomb their way from each side up those trenches which were in their hands. It is wonderful that troops which had already endured so much, and whose nerve might well be shattered and their hearts broken by successive failures, should still be able to carry out a form of attack which of all others call for dash and reckless courage. It was done, none the less, and with some success, the bombers blasting their way up Pearl Alley on the left to the point where it joins on to the Quadrangle Support. The bombers of the 7th Lincolns did particularly well. “Every attempted attack by the Boche was met by them with the most extraordinary Berserker fury. They utterly cowed the enemy.” So wrote an experienced spectator. On the right the 50th Brigade made some progress also up Quadrangle Alley. Artillery fire, however, put a term to the advance in both instances, the guns of Contalmaison dominating the whole position. In the evening a fresh bombing attack was made by the same troops, whose exertions seem really to have reached the limit of human capacity. This time the 7th Borders actually reached Quadrangle Support, but were unable to get farther. The same evening some of the 50th Brigade bombed down Wood Trench towards Mametz Wood, so as to facilitate the coming attack by the Thirty-eighth Division. On July 9 both Brigades again tried to bomb their way into Quadrangle Support, and were again held up by the enemy’s fire. This was the sixth separate attempt upon the same objective by the same soldiers — an example surely of the wonderful material of which the New Armies were composed.

But their labours were not yet done. Though both brigades were worn to shadows, it was still a point of honour to hold to their work. At 11:20 that night a surprise attack was made across the open under the cover of night. The 8th South Staffords on the left — charging with a yell of “Staffords!” — reached the point where Pearl Alley joins the Quadrangle Support (see Diagram), and held on most desperately. The 50th Brigade on the right were checked and could give no assistance. The men upon the left strove hard to win their way down Quadrangle Support, but most of the officers were down, the losses were heavy, and the most that they could do was to hold on to the junction with Pearl Alley. The 50th were ready to go forward again to help them, and the Yorkshire men were already on the move; but day was slowly breaking and it was doubtful if the trench could be held under the guns of Contalmaison. The attack upon the right was therefore stopped, and the left held on as best it might, the South Staffords, having lost grievously, nearly all their officers, including the Adjutant, Coleridge, being on the ground.

We may now leave this heroic tragedy of the of the Quadrangle and turn our attention to what had been going on at Mametz Wood upon the right, which was really the key to the situation. It has already been stated that the wood had been attacked in vain by a brigade of the Seventh Division, and that the Thirty-eighth Welsh Division had found some difficulty in even approaching it. It was indeed a formidable obstacle upon the path of the army. An officer has described how he used to gaze from afar upon the immense bulk, the vast denseness and darkness of Mametz Wood, and wonder, knowing the manifold dangers which lurked beneath its shadows, whether it was indeed within human power to take it. Such was the first terrible task to which the Welshmen of the New Army were called. It was done, but one out of every three men who did it found the grave or the hospital before the survivors saw the light shine between the further tree-trunks.

As the Welshmen came into the line they had the Seventeenth Division upon their left, facing Quadrangle Support, and the Eighteenth upon their right at Caterpillar Wood. When at 4:15 on the morning of July 10 all was ready for the assault, the Third Division had relieved the Eighteenth on the right, but the Seventeenth was, as we have seen, still in its position, and was fighting on the western edge of the wood.

The attack of the Welshmen started from White Trench, which lies south-east of the wood and meanders along the brow of a sharp ridge. Since it was dug by the enemy it was of little use to the attack, for no rifle fire could be brought to bear from it upon the edge of the wood, while troops coming over the hill and down the slope were dreadfully exposed. Apart from the German riflemen and machine-gunners, who lay thick among the shell-blasted stumps of trees, there was such a tangle of thick undergrowth and fallen trunks lying at every conceivable angle that it would take a strong and active man to make his way through the wood with a fowling-piece for his equipment and a pheasant for his objective. No troops could have had a more desperate task — the more so as the German second line was only a few hundred yards from the north end of the wood, whence they could reinforce it at their pleasure.

The wood is divided by a central ride running north and south. All to the west of this was allotted to the 113th Brigade, a unit of Welsh Fusilier battalions commanded by a young brigadier who is more likely to win honour than decorations, since he started the War with both the V.C. and the D.S.O. The 114th Brigade, comprising four battalions of the Welsh Regiment, was to carry the eastern half of the wood, the attack being from the south. The front line of attack, counting from the right, consisted of the 13th Welsh (2nd Rhonddas), 14th Welsh (Swansea), with its left on the central ride, and 16th Royal Welsh Fusiliers in the van of the 113th Brigade. About 4:30 in the morning the barrage lifted from the shadowy edge of the wood, and the infantry pushed forward with all the Cymric fire which burns in that ancient race as fiercely as ever it has done, as every field of manly sport will show. It was a magnificent spectacle, for wave after wave of men could be seen advancing without hesitation and without a break over a distance which in some places was not less than

The Swansea men in the centre broke into the wood without a check, a lieutenant of that battalion charging down two machine-guns and capturing both at the cost of a wound to himself. The 13th on the right won their way also into the wood, but were held for a time, and were reinforced by the 15th (Carmarthens). Here for hours along the whole breadth of the wood the Welsh infantry strove desperately to crawl or burst through the tangle of tree-trunks in the face of the deadly and invisible machine-guns. Some of the 15th got forward through a gap, but found themselves isolated, and had great difficulty in joining up with their own battle line once more. Eventually, in the centre and right, the three battalions formed a line just south of the most southern cross ride from its junction with the main ride.

On the left, the 16th Welsh Fusiliers had lost heavily before reaching the trees, their colonel, Garden, falling at the head of his men. The circumstances of his death should be recorded. His Welsh Fusiliers, before entering action, sang a hymn in Welsh, upon which the colonel addressed them, saying, “Boys, make your peace with God! We are going to take that position, and some of us won’t come back. But we are going to take it.” Tying his handkerchief to his stick he added, “This will show you where I am.” He was hit as he waved them on with his impromptu flag; but he rose, advanced, was hit again, and fell dead.

Mametz Wood

Thickened by the support of the 15th Royal Welsh Fusiliers, the line rushed on, and occupied the end of the wood until they were abreast of their comrades on the right. Once among the trees, all cohesion was lost among the chaos of tangled branches and splintered trunks, every man getting on as best he he might, with officers rallying and leading forward small groups, who tripped and scrambled onwards against any knot of Germans whom they could see. On this edge of the wood some of the Fusiliers bombed their way along Strip Trench, which outlines the south-western edge, in an endeavour to join hands with the 50th Brigade on their left. At about 6:30 the south end of the wood had been cleared, and the Welshmen, flushed with success, were swarming out at the central ride. A number of prisoners, some hale, some wounded, had been taken. At 7 o’clock the 113th were in touch with the 114th on the right, and with the 50th on the left.

Further advance was made difficult by the fact that the fire from the untaken Wood Support Trench upon the left swept across the ride. The losses of the two Fusilier battalions had been so heavy that they were halted while their comrades of the 13th Royal Welsh Fusiliers, under Colonel Flower, who was killed by a shell, attacked Wood Support — eventually capturing the gun which had wrought such damage, and about 50 Germans. This small body had succeeded, as so often before and since, in holding up a Brigade and disorganising an advance. Until the machine-gun is checkmated by the bullet-proof advance, the defensive will maintain an overpowering and disproportionate advantage.

The 10th Welsh had now come up to reinforce the left of the 114th Brigade, losing their colonel, Rickets, as they advanced into the wood. The 19th Welsh Pioneer Battalion also came forward to consolidate what had been won. There was a considerable pause in the advance, during which two battalions — the 17th Welsh Fusiliers and the 10th South Wales Borderers from the Reserve Brigade, 115th — came up to thicken the line. At about four, the attack was renewed, until at least two-thirds of the wood had been gained. The South Wales Borderers worked up the eastern side, pushing the defenders into the open, where they were shot down by British machine-guns in Caterpillar Wood and Marlborough Wood. About

During the night the 115th Brigade had come to the front, and in the morning of July 11 had relieved the 113th and 114th Brigades. The relief in a thick wood, swept by bullets, and upon a dark night in the close presence of a formidable enemy, was a most difficult operation. The morning was spent in reconnaissance, and it was only at 3. 15 P.M. that the advance could be made upon the main German defence, a trench just outside the north end of the wood. About 4 o’clock the Brigade swept on, and after a sharp bayonet fight gained the trench towards the north-east, but the Germans still held the centre and swept with their fire the portion in our possession. The 11th South Wales Borderers (2nd Gwents) held on splendidly, in spite of their heavy losses. The situation was now such, with only

The action of the Thirty-eighth Division in capturing Mametz Wood had been a very fine one, and the fruit of their victory was not only an important advance, but 398 prisoners, one field gun, three heavy guns, a howitzer and a number of smaller pieces. It was the largest wood in the Somme district, and the importance attached to it by the Germans may be gathered from the fact that men of five different German regiments, the 3rd Lehr, 16th Bavarians, 77th, 83rd, and 122nd, were identified among our opponents. Among many instances of individual valour should be mentioned that of a colonel of the Divisional Staff, who twice, revolver in hand, led the troops on where there was some temporary check or confusion. It is impossible to imagine anything more difficult and involved than some of this fighting, for apart from the abattis and other natural impediments of a tangled wood, the place was a perfect rabbit-warren of trenches, and had occasional land mines in it, which were exploded — some of them prematurely, so that it was the retreating Germans who received the full force of the blast. Burning petrol was also used continually in the defence, and frequently proved to be a two-edged weapon. Some of the garrison stood to their work with extraordinary courage, and nothing but the most devoted valour upon the part of their assailants could have driven them out. “Every man of them was killed where he stood,” said a Welsh Fusilier, in of the describing the resistance of one group. “They refused offers of quarter right to the last, and died with cheers for the Kaiser or words of defiance on their lips. They were brave men, and we were very sorry indeed to have to kill them, for we could not but admire them for their courage.” Such words give honour both to victors and vanquished. The German losses were undoubtedly very heavy — probably not less than those of the Welsh Division.