Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1323 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

The orders were peremptory, however, that the position should be taken, and General Maxse, without hesitation, threw a second of his brigades into the dangerous venture. It was the 54th Brigade which moved to the attack. It was just past midnight when the soldiers went. forward. The actual assault was carried out from south to north, on the same line as the advance of the West Kents. The storming battalions were the 6th Northamptons and 12th Middlesex, the former to advance direct through the and the latter to clean up behind them and to form a defensive flank on the right.

The attack was a fine feat of arms. Though heavily hit by the barrage, the Northamptons, closely followed by two companies of the Middlesex, pushed their way into the wood and onwards. It was pitch dark, and the men were stumbling continually over the fallen trees and the numerous dead bodies which lay among the undergrowth. None the less, they kept touch, and plodded steadily onwards. The gallant Clark was shot, but another officer led the Northamptons against the central strong point, for it had been wisely determined to leave no enemy in the rear. Shortly after dawn on July 14 this point was carried, and the Northamptons were able to get forward. By 8 o’clock the wood was full of scattered groups of British infantry, but the situation was so confused that the colonel went forward and rallied them into a single line which formed across the wood. This line advanced until it came level with the strong point S 3, which was captured. A number of the enemy then streamed out of the eastern side of the wood, making for Guillemont. These men came under British machine-gun fire and lost heavily. The remaining strong point at S1 had been taken by a mixed group of Buffs and Middlesex about

There was an epilogue which was as honourable to the troops concerned as the main attack had been. This concerns the fate of the men of West Kent, who, as will be remembered, had been cut off in the wood. The main body of these, under the regimental adjutant, together with a few men of the Queen’s, formed a small defensive position and held out in the hope of relief. They were about 200 all told, and their position seemed so hopeless that every excuse might have been found for surrender. They held out all night, however, and in the morning they were successfully relieved by the advance of the 54th Brigade. It is true that no severe attack was made upon them during the night, but their undaunted front may have had something to do with their immunity. Once, in the early dawn, a German officer actually came up to them under the impression that they were his own men — his last mistake upon earth. It is notable that the badges of six different German regiments were found in the wood, which seemed to indicate that it was held by picked men or volunteers from many units. “To the death!” was their password for the night, and to their honour be it said that they were mostly true to it. So also were the British stormers, of whom Sir Henry Rawlinson said: “The night attack on and final capture of Trones Wood were feats of arms which will rank high among the best achievements of the British Army.”

An account of this fortnight of desperate and almost continuous fighting is necessarily concerned chiefly with the deeds of the infantry, but it may fitly end with a word as to the grand work of the artillery, without whom in modern warfare all the valour and devotion of the foot-soldier are but a useless self-sacrifice. Nothing could exceed the endurance and the technical efficiency of the gunners. No finer tribute could be paid them than that published at the time from one of their own officers, which speaks with heart and with knowledge: “They worked their guns with great accuracy and effect without a moment’s cessation by day or by night for ten days, and I don’t believe any artillery have ever had a higher or a longer test or have done it more splendidly. And these gunners, when the order came that we must pull out and go with the infantry — do you think they were glad or willing? Devil a bit! They were sick as muck and only desired to stay on and continue killing Boches. And these men a year ago not even soldiers — much less gunners! Isn’t it magnificent — and is it not enough to make the commander of such men uplifted?” No cold and measured judgment of the historian can ever convey their greatness with the conviction produced by one who stood by them in the thick of the battle and rejoiced in the manhood of those whom he had himself trained and led.

The Second German Line, Bazentins, Delville Wood, etc.

VI. THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

The Breaking of the Second Line. July 14, 1916

The great night advance — The Leicester Brigade at Bazentin — Assault by Seventh Division — Success of the Third Division — Desperate fight of Ninth Division at Longueval — Operations of First Division on flank — Cavalry advance

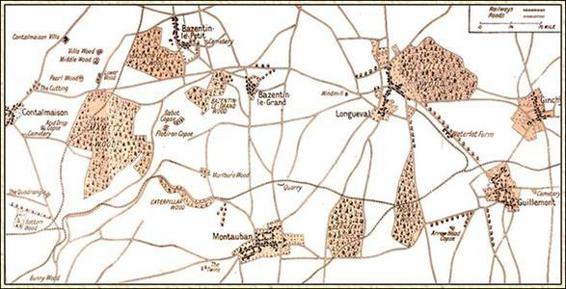

WITH the fall of Mametz Wood, the impending capture of Trones Wood upon the right, and the close investment of Ovillers upon the left flank, the army could now face the second line of German defences. The ground in front of them sloped gently upwards until it reached the edge of a rolling plateau. Upon this edge were three villages: Little Bazentin upon the left, Grand Bazentin upon the centre, and Longueval upon the right, all nestling among orchards and flanked by woods. Through these lay the enemy’s position, extending to Pozières upon the one side, and through Guillemont to the French junction on the other. These two flanks were for the time to be disregarded, and it was determined to strike a heavy frontal blow which would, as it was hoped, crush in the whole middle of their line, leaving the sides to be dealt with at our leisure. It was a most formidable obstacle, for all three villages were as strong as the German sappers could make them, and were connected up with great lines of trenches, the whole front which was to be attacked covering about

The heavy guns had been advanced and the destruction of the German wire and trenches had begun upon July 11. On the evening of the 13th the troops mustered for the battle. They were all divisions which had already been heavily engaged, and some of them had endured losses in the last fortnight which might have seemed to be sufficient to put them out of action. None the less they were not only eager for the fight, but they were, as it proved, capable of performing the most arduous and delicate of all operations, a night march in the face of the enemy. More than a thousand yards of clear ground lay at many points between the British outposts and the German trenches. To cover it in daylight meant, as they had so often learned, a heavy loss. It was ordered, therefore, that the troops should move up to within striking distance in the darkness, and dash home with the first glimmer of morning light. There was no confusion, no loss of touch as 25,000 stormers took up their stations, and so little sound that the Germans seem to have been unaware of the great gathering in their immediate front. It was ticklish work, lying for hours within point-blank range with no cover, but the men endured it as best they might. With the first faint dawn the long line sprang to their feet and with a cheer dashed forward at the German trenches, while the barrage rose and went roaring to eastward whence help might come to the hard-pressed German defence.

On the extreme left of the section attacked was the First Regular Division, which took no part in the actual advance but held the flank in the neighbourhood of Contalmaison Villa, and at one period of the day sent forward its right-hand battalion, the 1st North Lancashires, to aid their neighbours in the fight.

The left of the line of actual attack was formed by the Twenty-first Division opposite to Bazentin-le-Petit. This attack was carried out upon a single brigade front, and the Brigade in question was the 110th from the Thirty-seventh Division. This division made no appearance as a unit in the Battle of the Somme, but was several times engaged in its separate brigades. On this occasion the 110th, consisting entirely of men of Leicester, took the place of the 63rd Brigade, much reduced by previous fighting. Their immediate objective was the north end of Bazentin-le-Petit village and the whole of the wood of that name. Led by the 8th and 9th Leicesters the brigade showed, as has so often been shown before, that the British soldier never fights better than in his first engagement. Owing to the co-operation of the First Division and to a very effective smoke screen upon their left, their advance was not attended with heavy loss in the earlier stages, and they were able to flow over the open and into the trenches opposite, capturing some 500 prisoners. They continued to fight their way with splendid steadiness through the wood and held it for the remainder of the day. Their greatest trouble came from a single German strong-point which was

On the right of the Twenty-first Division lay the Seventh Division, to which had been assigned the assault of the Bazentin-le-Petit village. The leading brigade was the 20th, and the storming battalions, the 8th Devons and 2nd Borders, crept up to their mark in the darkness of a very obscure night. At 3.25 the barrage was lifted, and so instantaneous was the attack that there was hardly an interval between the last of the shrapnel and the first of the stormers. The whole front line was captured in an instant, and the splendid infantry rushed on without a pause to the second line, springing into the trenches once more at the moment that the gunners raised their pieces. In ten minutes both of these powerful lines had fallen. Several dug-outs were found to be crammed with the enemy, including the colonel of the Lehr Battalion, and with the machine-guns which they had been unable to hoist into their places before the wave had broken over them. When these were cleared, the advance was carried on into Bazentin-le-Grand Wood, which was soon occupied from end to end. A line in front of the wood was taken up and consolidated.

In the meanwhile the 22nd Brigade had taken up the work, the 2nd Warwicks pushing forward and occupying, without any opposition from the disorganised enemy, the Circus Trench, while the 2nd of the Royal Irish advanced to the attack of the village of Bazentin-le-Petit. Their leading company rushed the position with great dash, capturing the colonel commanding the garrison, and about 100 of his men. By 7:30 the place was in their hands, and the leading company had pushed into a trench on the far side of it, getting into touch with the Leicesters on their left.

The Germans were by no means done with, however, and they were massing thickly to the north and north-east of the houses where some scattered orchards shrouded their numbers and their dispositions. As the right of the brigade seemed to be in the air, a brave sergeant of the 2nd Warwicks set off to establish touch with the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, who formed the left unit of the Third Division upon the right. As he returned he spotted a German machine-gun in a cellar, entered it, killed the gunner, and captured four guns. The wings of the two divisions were then able to co-operate and to clear the ground in front of them.

The Irishmen in the advance were still in the air, however, having got well ahead of the line, and they were now assailed by a furious fire from High “Wood, followed by a determined infantry assault. This enfilade fire caused heavy losses, and the few survivors of those who garrisoned the exposed trench were withdrawn to the shelter afforded by the outskirts of the village. There and elsewhere the Lewis guns had proved invaluable, for every man of intelligence in the battalion had been trained to their use, and in spite of gunners being knocked out, there was never any lack of men to take their place. The German counter-attack pushed on, however, and entered the village, which was desperately defended not only by the scattered infantrymen who had been driven back to it, but also by the consolidating party from the 54th Field Company Royal Engineers and half the 24th Manchester Pioneer Battalion. At this period of the action a crowd of men from various battalions had been driven down to the south end of the village in temporary disorganisation due to the rapidity of the advance and the sudden severity of the counterattack. These men were re- formed by the adjutant of the Irish, and were led by him against the advancing Germans, whom they drove back with the bayonet, finally establishing themselves on the northern edge of Bazentin-le-Petit Wood, which they held until relieved later by the 2nd Gordons of the 20th Brigade. At the same time the village itself was cleared by the 2nd Warwicks, while the 1st Welsh Fusiliers drove the Germans out of the line between the windmill and the cemetery. The trench held originally by the Irish was retaken, and in it was found a British officer, who had been badly wounded and left for a time in the hands of the enemy. He reported that they would not dress him, and prodded at him with their bayonets, but that an officer had stopped them from killing him. No further attempt was made by the Germans to regain the position of Bazentin. The losses, especially those of the Royal Irish, had been very heavy during the latter part of the engagement.

Much had been done, but the heavy task of the Seventh Division was not yet at an end. At 3:20 P.M. the reserve Brigade (91st) were ordered to attack the formidable obstacle of High Wood, the 100th Brigade of the Thirty-third Division (Landon) co-operating from the left side, while a handful of cavalry from the 7th Dragoon Guards and 20th Deccan Horse made an exhilarating, if premature, appearance upon the right flank, to which some allusion is made at the end of this chapter. The front line of the 91st Brigade, consisting of the 2nd Queen’s Surrey and 1st South Staffords, marched forward in the traditional style of the British line, taking no notice of an enfilade fire from the Switch Trench, and beating back a sortie from the wood. At the same time the Brigadier of the 100th Brigade upon the left pushed forward his two leading battalions, the 1st Queen’s Surrey and the 9th Highland Light Infantry, to seize and hold the road which led from High Wood to Bazentin-le-Petit. This was done in the late evening of July 14, while their comrades of the Seventh Division successfully reached the south end of the wood, taking three field guns and 100 prisoners. The Queen’s and part of the Highland Light Infantry were firmly in possession of the connecting road, but the right flank of the Highlanders was held up owing to the fact that the north-west of the wood was still in the hands of the enemy and commanded their advance. We will return to the situation which developed in this part of the field during the succeeding days after we have taken a fuller view of the doings upon the rest of the line during the battle of July 14. It may be said here, however, that the facility with which a footing was established in High Wood proved to be as fallacious as the parallel case of Mametz Wood, and that many a weary week was to pass, and many a brave man give his heart’s blood, before it was finally to be included in the British lines. For the present, it may be stated that the 91st Brigade could not hold the wood because it was enfiladed by the uncaptured Switch Trench, and that they therefore retired after dusk on the 15th.

To return to the story of the main battle. The centre of the attack was carried out by the Third Division, one of the most famous units in the Army, though it now only retained three of the veteran battalions which had held the line at Mons. The task of the Third Division was to break the centre of the German line from Grand Bazentin upon the left where it touched the Seventh to Longueval on the right where it joined with the Ninth Division. The 8th Brigade was on the right, the 9th upon the left, while the 76th was in support. The attacking troops advanced in the darkness in fours, with strong patrols in front, and deployed within

The left brigade had been more fortunate, finding the wire to be well cut. The front trench was not strongly held, and was easily carried. Both the King’s Liverpools and the West Yorkshires got through, but as they had separated in the advance the greater part of the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers were thrust into the gap and restored the line. These men, supported by Stokes guns, carried the village of Grand Bazentin by 6:30 A.M. There was a deadly fire from the Grand Bazentin Wood upon the left, but as the Seventh Division advanced this died away, and the 12th West Yorkshires were able to get round to the north edge of the village, but could get no farther on account of the hold-up of the 8th Brigade upon the right. There was a considerable delay, but at last by 1 P.M. a renewed bombardment had cut the wires, and strong bombing parties from the supporting battalions, the 2nd Royal Scots and 1st Scots Fusiliers, worked down the front trench from each end. The whole brigade was then able to advance across the German front line, which was at once consolidated.

The losses in this attack had been heavy, the 12th West Yorkshires alone having 15 officers, including their colonel, and 350 men out of action. The results, however, were solid, as not only was the whole front of the German position crushed in, but 36 officers with 650 men were taken, together with four small howitzers, four field-guns, and fourteen machine-guns. A counter-attack was inevitable and consolidation was pushed forward with furious energy. “Every one was digging like madmen, all mixed up with the dead and the dying.” One counter-attack of some hundreds of brave men did charge towards them in the afternoon, but were scattered to the winds by a concentration of fire. The position was permanently held.