Democracy of Sound (13 page)

Read Democracy of Sound Online

Authors: Alex Sayf Cummings

Tags: #Music, #Recording & Reproduction, #History, #Social History

Numerous bootleggers scrambled to get out of the business after the public demise of Jolly Roger, but piracy persisted. In some instances organized crime sought to take advantage of the ephemeral popularity of a hit single by dumping its own copies of 45s on the market. In 1960 Robert Arkin of the Bronx and Milton Richman of Queens were charged with copying Cameo singles of rock and roller Bobby Rydell’s “Ding-A-ling” and “Wild One.” Operating out of Fort Lee, New Jersey, their Bonus Platta-Pak company worked with an accomplice in Hollywood named Brad Atwood.

107

In October seven men were arrested in Los Angeles, including Atwood. “More than half the shelf stock in [Los Angeles] county of one particular recording were bogus reproductions,” the

Los Angeles Times

reported. “Undercover agents wormed their way into the ring and were actually helping load records purchased by two other agents of the district attorney when yesterday’s raids were made. [District Attorney] McKesson said the bootleggers were making their reproductions using facilities of legitimate record manufacturing firms at night and on weekends.”

108

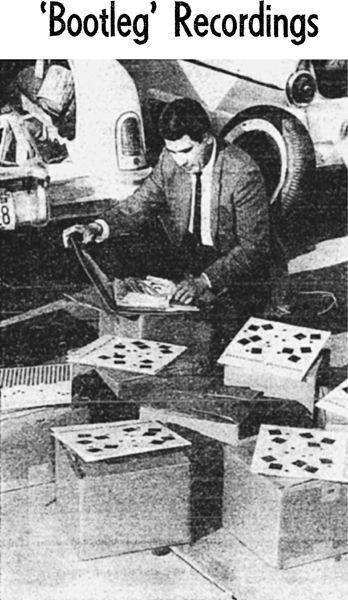

Figure 2.5

Balt Yanez of the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office examines boxes of bootleg records confiscated in an elaborate sting against a pirate network that linked North Hollywood to Bergen County, New Jersey.

Source

: “Fake Record Ring Broken; 7 Men Held,”

Los Angeles Times

, October 3, 1960, 2–3. Reprinted by permission of

Los Angeles Times

.

More persistent were the small entrepreneurs who copied records that the major labels had no interest in reissuing. In the 1960s, many bootlegs entered the United States from abroad. Pirate Records of Sweden made available the likes of Barbecue Bob and Blind Lemon Jefferson, blues singers of the 1920s and 1930s. The label pressed records in batches of 100 and requested correspondence in English or French.

109

Swaggie, based in Melbourne, Australia, reprinted records from as far back as 1917, including well-known performers like Sidney Bechet and lesser-known acts from the 1920s, such as Tampa Red’s Hokum Jug Band. The Swaggie catalog plainly listed which labels had originally released the material, and label head Nevill L. Sherburn wherever possible pursued licensing agreements with artists and record companies to reissue their work.

110

In 1966, the manager of Fats Waller’s estate even asked Steve Sholes at RCA Victor if the label would work with Swaggie in releasing some lost recordings Waller had made while working for Victor:

Can something be arranged for Swaggie on the V Discs made by Fats on that memorable session, when Old Granddad flowed fluently … as Fats would remark … and all concerned had a ball.… “Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die.” That was Fats’ motto thruout his short lifetime and that date on September 23, 1943 … turned out to be “fini” at Victor. I sincerely hope that something can be arranged [to] get these records on the market, for they contain numbers from the musical “Early to Bed” … Fats’ Broadway musical which was never recorded because of the musicians strike.

111

Ed Kirkeby’s request did not find a sympathetic ear. The letter ended up in the files of RCA’s Brad McCuen, who since 1964 had investigated labels such as Folkways for allegedly reissuing Victor’s old blues, folk, and jazz records.

112

During his research, McCuen learned of the Jolly Roger incident and the surge of piracy in the early 1950s. Writing to Sholes, he compared the new wave of copiers to the Blue Aces and Jazz Panoramas of old. “There are now at least a dozen labels openly offering for sale our masters without permission,” McCuen wrote. “Included are the labels Palm Club, Swaggie, OFC, Historic Jazz, Limited Editions, Pirate (Sweden),

etc.

I feel we should discuss making a stand against these illegal labels if for no other reason than to protect our Vintage futures.”

113

McCuen’s goal was to protect his employers’ long-term corporate interest in securing exclusive control of their recordings, even if the company did not necessarily intend to produce and sell them. The prevalence of firms like Swaggie indicated that the desire for old records had not slackened, as entrepreneurs moved to fulfill the demand formerly met by the likes of Hot Record Society and Jolly Roger.

Table 2.1

RCA’s List of Suspected Pirate Labels in the Mid-1960s

Name | Details |

1. Swaggie Records | Box 125, South Yarra, Melbourne Australia. Probable owner: Nevill L. Sherburn |

2. RFW Records | Box 746, San Fernando, California 91340. Fats Waller |

3. Palm Club Records | V-Discs, E.T.S |

4. Testament Records | Library of Congress |

5. RBF Records | Subsidiary of Folkways Records |

6. Historical Jazz | Box 4204, Bergen Station, Jersey City, New Jersey 07304 |

7. Roy Morser | Box 225, Gracie Station, NYC 10028. Duplicators. |

8. Pirate Records | Box 11063, Stockholm, 11, Sweden |

9. Old Timey Records | Box 5073, Berkeley, California. Subsidiary of Arhoolie Records. Owner: Chris Strachwitz. Specialized in country & western |

10. Blues Classics Records | Blues and jug bands |

11. Origin Records | Blues |

12. County Records | Country & western |

13. Max Abrams | 1108 Celis Street, San Fernando, California. Duplicator |

14. OFC Records | Probably European import |

15. Folkways Records | 165 W. 46 Street, NY, NY 10036. Owner: Moe Asch. Jazz and folk. |

16. Melodeon Records | Spottswood Music Company, 3323 14 Street N.E. Washington, DC, 20017. Owner: Richard Spottswood |

17. FDC Records | Probably of European origin. Jazz |

18. Jazz Panorama | |

19. Jazz Society Records | Sold through John Norris, Box 87, Toronto 6, Ontario, Canada. |

Source

: “Labels,” Brad McCuen Collection—Piracy 1969, 97-023, box 18, folder 9, MTSUCPM.

The ultimate question remained: who should be the stewards of the ever-growing legacy of recorded music? Should the companies that originally recorded and marketed the music decide whether it would remain available to the public, beyond the worn-out relics hoarded by collectors? Should

music lovers be able to keep copies of old recordings in circulation despite the industry’s disinterest or active opposition? Given the up-front costs involved in recording, advertising, and distributing an original recording, large firms such as RCA Victor could maximize their profits by selling large numbers of a few popular releases, rather than offering the public a wide range of records that each sold fewer copies.

114

A reissue of an obscure Sidney Bechet side, catering to perhaps a few hundred avid collectors, seemed a waste of RCA’s sales staff and productive capacity.

Since the means of production—record-pressing plants—remained concentrated in the hands of a few major labels in the 1950s, those firms could exercise a wide degree of discretion about what music was available to the public. The American music industry of the 1940s and early 1950s was highly consolidated in a few firms, who sought to vertically integrate production and to deter competitors from entering the market.

115

And as legal scholar James Boyle has stressed, the vast majority of works go out of print in a few years. In many cases the actual owner of the work is difficult to determine (so-called “orphan works”), and even when the owners can be identified, they hold the power to decide whether to reproduce it or license the rights. Given these conditions, collectors and bootleggers alike feared that countless items of recorded music would become scarce and inaccessible as they receded into the past.

116

The Jolly Roger case shows that entrepreneurs who wanted to market recordings to smaller, niche markets had to turn to the custom-pressing services of companies like RCA to have their records made, drawing on the infrastructure of the major labels to copy records that those firms no longer had an interest in selling. The persistence of outfits such as Swaggie and Pirate Records suggests that the mainstream industry’s efforts to satisfy the demand for such music, once they recognized it, with reissue programs failed to provide the full range of out-of-print recordings desired by fans and collectors. Confusion about the ownership of recorded music left unclear who should decide whether a record would remain in circulation, and the Jolly Roger flap marked the beginning of the industry’s effort to protect a newly understood value in recorded sound from the encroachment of unauthorized reproduction—a campaign that would bear fruit with the provision of copyright for sound recordings in 1971. Until then, the labels sought to deter anyone from copying the records that they no longer wanted to sell, with the aim of keeping such music unavailable until the established firms saw fit to reissue it.

This struggle only occurred because bootlegging showed the labels that their back catalog might be worth something—that recorded music retained meaning and significance in which the public had an interest long after it stopped being worthwhile for companies to keep in circulation. Collectors insisted that there was something uniquely valuable about each record, each variation, which

copyright law had treated as incidental to the essence of the work. It was collecting that led to bootlegging, and bootlegging that led to legal suppression and, eventually, to an expansion of copyright restrictions that would make collecting more difficult. The primacy of performance and interpretation in jazz helped prompt this reconsideration of copyright. Some elements of creativity could not be captured in musical notation—the characteristic playing of an instrument with its own timbre, for instance—although American copyright law did not recognize them until the early 1970s. The wave of successful anti-bootlegging litigation in the 1950s followed a spike in the popularity of jazz bootlegs that jolted the record companies into action. But the industry’s victory over Jolly Roger was short-lived. In the 1950s and 1960s, new media such as magnetic tape made recording cheaper and easier than before, and lovers of opera and other less-than-profitable genres argued that their copying served a wholesome purpose by capturing and preserving music that would otherwise sink in the commercial marketplace. And in the late 1960s, not long after McCuen hunted the copiers of folk and jazz, bootleggers turned to rock and roll, provoking a bigger legal battle than seen in the skirmishes of the 1950s.

|| 3 ||

Piracy and the Rise of New Media

The corrupt police captain Hank Quinlan sat in the parlor of his old flame Tanya, after a drunken bender took him south of the Rio Grande. Bleary-eyed and exhausted, Quinlan was comforted by the tinny sound of an antique player piano. “The customers go for it,” Tanya said. “It’s so old, it’s new.” Outside, the Mexican official Miguel Vargas waited with a tape recorder, hoping to capture evidence of Quinlan’s dishonesty that could clear the good name of Vargas’s wife, who had been framed for murder. Throughout the climactic scenes of Orson Welles’s 1958 film

Touch of Evil

, Vargas lurks in the shadows, following close behind the police chief and his erstwhile sidekick Menzies, who wears a wire. Meanwhile, the staccato ragtime of the player piano plods along in the background.

1

The juxtaposition of an old medium—one of the earliest ways of mechanizing music—and the new technology of the magnetic tape recorder paralleled the difference between Vargas and Quinlan. The former was a young, progressive law enforcement official, while the latter was a bloated, racist “good old boy” who ruled the American side of the border as his own personal fiefdom. In due time, the old guard was done in by the cleverness and diligence of the new.

Touch of Evil

reflects the emergence of new media in the 1950s, a decade when the use of magnetic recording spread beyond the military and industry and into the consumer marketplace in the United States. The transformation of this long-dormant technology into a medium that was accessible to large numbers of people challenged property rights by enabling new ways of using sound that had not been known to the jazz copiers of the 1930s and 1940s.