Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (89 page)

Read Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China Online

Authors: Ezra F. Vogel

Although Zhao acknowledged errors, he was not ready to be the pawn completely sacrificed to protect the king. He did not announce in a prominent public way that the responsibility for the decision to free up price controls was his. Knowledgeable party officials reported that though Deng continued to support Zhao as general secretary of the party, relations between Zhao and Deng were strained because Deng was held responsible by both high-level party officials and the public for taking the lid off prices.

Following the public panic of August and the weakening of the power of Deng and Zhao, the cautious planners quickly regained control of economic policy. On September 24, 1988, the State Council promulgated a document stating that the focus of work for the next two years would be “improving the economic environment.” No one familiar with Chen Yun's readjustment policies of 1979–1981 could have been surprised by the economic policies of 1988 when the cautious balancers took control. No new price adjustments were approved in 1988. Enterprises and work units were told not to raise prices. The People's Bank of China, which had been paying interest rates far below inflation rates, guaranteed that if necessary, deposits would be raised in value to keep pace with inflation. Localities were told to scale back capital construction.

57

Investments were cut back and price controls tightened. Bank credit was stringently controlled and loans to TVEs were suspended. In the 1990s Zhu Rongji would manage to bring inflation under control with a soft landing, but in late 1988 Chen Yun was as bold in stopping inflation as Deng

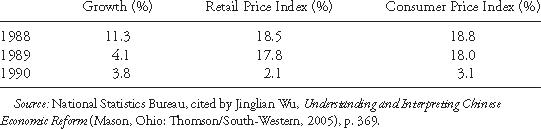

had been in removing price controls. Not surprisingly, in late 1988 there was a hard landing, as we see from declines in growth during the subsequent years:

Due to the combination of economic controls and political decisions between 1988 and 1990, the GNP growth rate fell from 11 percent in 1988 to 4 percent in 1989, and the industrial growth rate fell from 15 percent to 5 percent. By the last quarter of 1990, the increase in the retail price index had dropped to 0.6 percent.

58

Consumer spending remained sluggish, unemployment mounted, and signs of unrest appeared in many cities. Planners still aimed to narrow the budget deficit, but because of the lower tax base, the budget deficit actually grew. Yet despite these unsettling economic indicators, for three years after the outbreak of opposition to the lifting of price controls, Deng could not muster support within the party to challenge Chen Yun's contraction policies.

Chinese and Soviet Reforms: A Comparison

The socialist planning system, which was first introduced into the Soviet Union and later into China to help late-developing countries catch up with the early industrializing areas, enabled China to accumulate capital and channel resources into high-priority areas. As it had earlier in the Soviet Union, this planning system allowed China to develop heavy industry in the 1950s. In the 1970s, however, the economies of both countries had fallen far behind those of countries with more open, competitive systems. Yet by 1991, when communism fell apart in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, China could boast average growth of 10 percent a year since 1978. What had enabled China to outperform the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the 1980s?

China had many advantages over the Soviet Union. It had a long coastline that made ocean transport less expensive and far easier to expand than land transport. As a source of capital and knowledge, mainland China could call

on a pool of some 20 million Chinese émigrés and their descendants who in the previous two centuries had left mainland China for Hong Kong, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and the West. Moreover, the vast potential mainland Chinese market encouraged many businesspeople around the world to offer help so that they might eventually access this pool of one billion customers. Political motives played a part as well: after China began its opening in 1978, many Western countries, eager to wean China away from the Soviet Union, were willing to be generous to China in terms of passing on capital and technology and in welcoming students and visitors.

Geography and ethnic homogeneity also played important roles in China's success. The boost in enthusiasm and agricultural output from dividing collective rice paddy fields could not be duplicated in the Soviet Union, where the large dry fields could be better farmed with large tractors. It was also easier to unify a country like China, in which 93 percent of the population came from the same ethnic group, than a country where over half the population came from diverse ethnic groups. The Soviet Union had expanded to a broad geographical area within the previous century by annexing minority groups that were either actively or passively resistant to Soviet authority. China, by contrast, had ruled most of its geographical area for over two millennia and was not overextended by occupying other countries resistant to its leadership.

Chinese leaders, too, had a confidence that came from the country's long history as the center of civilization, whereas Soviet leaders had long been aware that the USSR lagged far behind the Western European countries. And finally, China's neighbors—Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, which shared some common cultural characteristics—had recently made the transition to become rich modern countries that could serve as models for China.

But whatever intrinsic advantages China might have enjoyed, at key points Deng made choices different from those made by his Soviet counterparts, choices that proved to be far more successful in stimulating economic growth.

59

First, he maintained the authority of the Communist Party. In the Soviet Union, Gorbachev hoped to develop a new system of governance by abolishing the monopoly of power by the Soviet Communist Party. But Deng never wavered in his faith that the Chinese Communist Party, originally modeled after the Soviet Communist Party, should be retained as the sole governing structure in China. In Deng's view, only the party could provide the core of loyalty, discipline, and commitment that was needed to provide

stable leadership for the country. His belief that China needed to be led by a single ruling party was shared by all three of the other major Chinese leaders in the twentieth century—Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek, and Mao Zedong.

Yet Deng was also realistic about changes that needed to be made: he knew that the party he had inherited in 1978 was bloated with dead wood and unable to provide the leadership needed for modernization. He was convinced that many senior Communist Party officials, especially those who had risen during the political struggles of the Cultural Revolution, were useless in providing leadership for modernization. He did not expel many of them outright from the party, since doing so would have been disruptive, polarized the party, and distracted attention from dealing with the real problems the country faced. But he did quietly push them out of the most important positions, giving their jobs to those who could provide leadership for modernization. Indeed, Deng took great care to select able officials for the top positions, and he encouraged lower-level leaders to do the same. Once selected, these teams of leaders were given considerable leeway to make progress.

Deng advanced step by step, rather than with a “big bang.” After 1991, Russia had followed the advice of economists who recommended opening markets suddenly, with a “big bang.” In contrast, Deng, with the advice of experts brought in by the World Bank, accepted the view that a sudden opening of markets would lead to chaos. He understood what many Western economists who took institutions for granted did not: that it was vitally important to take the time to build national institutions with structures, rules, laws, and trained personnel adapted to the local culture and local conditions. China did not have the experience, rules, knowledgeable entrepreneurs, or private capital needed to convert suddenly to a market economy. Deng knew that it had taken many decades in nineteenth-century Japan and later in the other East Asian economies to build institutions appropriate to catch up with the West. He could not suddenly disband China's existing state enterprises without causing massive unemployment, a result that would have been politically and socially unsustainable. So he allowed Chen Yun and others to keep the old system functioning to provide a stable economic base while he permitted markets to grow, people to gain experience, and institutions to adapt to a more open economy. Deng did not impose the new structures—household agriculture, TVEs, or private enterprises. Instead, he let the local areas try out these experiments, publicizing any successes to allow other areas to adapt them to their own circumstances.

Underpinning all of Deng's strategies was a commitment to opening China fully to ideas and trade with the outside world. Soviet leaders had been cautious about allowing foreign businesspeople and foreign businesses to establish enterprises in the Soviet Union, and were worried about sending large numbers of Soviet students abroad. Deng knew China would face huge adjustment problems from changes wrought by outsiders and from returning students, but he firmly believed that nations grow best when they remain open. Unlike some of his colleagues who feared that China would be overwhelmed by foreigners and foreign practices, Deng was confident that the Communist Party was strong enough to control them. He strongly supported sending officials and students abroad, translating foreign books and articles, and welcoming foreign advisers and businessmen to China. He was prepared to face criticism from those who feared that Chinese lifestyles and interests would be adversely affected by foreign competition. He believed competition from foreign companies would not destroy the Chinese economy but rather stimulate Chinese businesses to become stronger. He also did not worry if a substantial percentage of those who went abroad did not return, for he believed that they too would continue to help their motherland.

The process that propelled China's dramatic opening in the 1970s and 1980s did not begin with Deng Xiaoping. Instead Mao first began to open the country after clashes with the Soviet Union in 1969, and both Zhou Enlai and Hua Guofeng continued his initiative. But Deng was unique in that he pushed the doors open far wider—to foreign ideas, foreign technology, and foreign capital—than his predecessors, and he presided over the difficult process of expanding the opening despite the disruptions it caused. Radiating his deep confidence in China's potential and maneuvering skillfully through political obstacles, he set the stage for a new era in Chinese history. With Deng at the helm, the Chinese people were willing to swallow their pride, admit their backwardness, and keep learning everything they could from abroad.

Throughout China's imperial history, as dynasties declined, territory along the country's long borders would begin to slip away from central control, only to be reclaimed and fortified by the bold warriors who founded the next dynasty. In the 1890s, as the Qing, China's last dynasty, was declining, Li Hongzhang, a Chinese official facing much stronger Western powers, was forced to sign the “unequal treaties,” which gave the Western nations control over territory along the Chinese coast. After China lost the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), Li signed away Taiwan to Japan, and in 1898, he signed the lease passing Hong Kong's New Territories to the British. For yielding China's rights to foreigners, Li was regarded as a traitor, and indeed he became one of the most vilified officials in Chinese history. Mao Zedong, like the strong warriors before him who had founded China's great dynasties, regained most of China's territory lost by the late Qing—Shanghai, Qingdao, and elsewhere—but he was unable to recover possession of Taiwan and Hong Kong. That task would fall to Deng.

1

Unlike emperors before him, Mao had access to radios, movies, the press, and a modern propaganda structure to marshal public support for patriotic goals. He was particularly successful in mobilizing Chinese youth, who were outraged at the past humiliations of their great civilization. Once Communist leaders had fanned the flames of nationalism to build support for their struggle, no Chinese leader—certainly not Deng Xiaoping—could consider betraying that popular sentiment. Indeed, when he took command, Deng Xiaoping regarded regaining Taiwan and Hong Kong as among his most sacred responsibilities.

Deng also worked to firm up control over areas inside China's borders. Many of China's borders to the north, west, and south were mountainous regions where minorities were eking out an existence even closer to subsistence level than were the peasants on the flatlands. Most minority groups lacked the scale, the organization, and the foreign support to challenge Beijing's efforts to control them. But Tibet was different. More than a millennium earlier Tibetans had claimed a geographical area almost as large as China, and as Tibetan territory had contracted over time, small communities of Tibetans had remained behind in several Chinese provinces. Tibetans had temples and monasteries that could become centers for resistance to Chinese rule. In Deng's era, they were supported by a large, politically active community of exiles in India who remained hostile to China. Above all, Tibetans had the leadership of the Dalai Lama, who inspired a worldwide following beyond that of any other Asian leader.