Desperate Husbands (8 page)

Read Desperate Husbands Online

Authors: Richard Glover

I feel sexier. More primitive. I prowl the kitchen, looking for my mate. I spot Jocasta by the toaster, trying to fish out an English muffin that has become stuck. She is dressed, alluringly enough, in spotty pyjamas and ugh boots. I growl and beat my chest. ‘Come on, baby. You haven’t the time for muffins. Marriage is about procreation. It’s about the survival of the species.’

Politicians both here and in the US have been talking about gay marriage. We can’t allow gay marriage, said both the Prime Minister and the President, because marriage is about the continuation of the species. Suddenly, ever since they spoke, I see myself in a new light, as the last of my species, swinging from tree to tree. I am the last of a mighty line, the last large-arsed male Bo-Bo still alive in the jungle. I must find another large-arsed Bo-Bo and breed. ‘Come on,

Jocasta,’ I say, leaning closer. ‘We must multiply, for marriage has no point without procreation.’

‘I’ve already multiplied,’ she mumbles distractedly, ‘and now I want some breakfast.’

‘But Bo-Bo want to breed. Bo-Bo want species to continue.’ I beat my chest but to no avail. Sometimes I suspect Jocasta takes no notice of the Prime Minister at all. Nor the President. ‘Poor Bo-Bo,’ I mumble, stumbling out into the backyard in order to urinate against a tree.

So many species have become extinct, but until now I’d never spotted the connection with gay marriage. The dodo. The Tahitian sandpiper. The Tasmanian tiger. Presumably all of them, at one point or another, relented and allowed gay marriage. Next thing:

poof

. The whole species gone. The Mauritian flying fox. The Tongan giant skink. The spectacled cormorant. All victims of gay marriage.

Take the mystery of the dinosaurs. For millions of years they dominated the earth. And then suddenly they were extinct. The Prime Minister and the President may be the first to have solved the mystery. The dinosaurs must have allowed gay marriage. A few years on and the whole institution of dinosaur marriage was sapped of meaning. The straight dinosaurs began standing around in ugh boots, toasting muffins and forgetting to procreate.

It takes a pretty special Prime Minister to understand this sort of hidden evolutionary history. We are indeed a lucky people.

Certainly I’m starting to see Jocasta in a new light. She is not so much a woman as the bearer of her evolutionary history. ‘You are primeval slime,’ I say to her, ‘phylogenically speaking.’

‘There’s no need to talk like that, just because I won’t come across,’ she responds, with a mouthful of muffin.

‘No, it’s wonderful,’ I continue. ‘You were slime which then divided asexually. You turned into a tiny sea creature, clambered onto land, grew wings and experimented with flight, then evolved into a mammal.’

Jocasta takes another bite of toast. ‘No wonder I’m tired.’

‘Only recently,’ I continue, ‘have we learnt to walk erect.’

‘Well,’ Jocasta says, staring at my pyjamas and pointing with her muffin, ‘you don’t seem to be having trouble in that regard. Not this morning.’

It’s true that I, Bo-Bo, stand ever-ready to attempt the continuation of the species. In the past some males have been embarrassed by this ever-readiness. But no longer: not since the Prime Minister and the President explained what marriage is all about. I look downwards and what I see is now bathed in a sort of heroic light. In my mind’s ear, I hear trumpets playing. A choir of angels sings off to the side.

‘The Prime Minister is right,’ I say to Jocasta. ‘The very species, it depends on me. It depends on

this

.’ I gesture downwards, hoping she will share my sense of awe.

Somewhere in the mind of men always lurked this knowledge. We knew

it

was the centre of life itself; a thing not only of beauty but of historical importance. For years we had shown it to others, hoping they would see it in the same way. Backlit somehow. Significant. Inspiring. But instead there was constant disappointment. Constant mockery. There were those who laughed. Those who crinkled their noses in distaste. And those many who just let loose a disappointed: ‘Oh, is that all.’ Until now.

‘Bo-Bo is but a tool of evolution,’ I say to Jocasta tenderly.

‘Certainly Bo-Bo is a tool,’ she says, popping the last of the muffin into her mouth.

‘But marriage has no point without constant procreation,’ I say. ‘The Prime Minister says so.’

Jocasta slings her plate in the sink and heads to work. ‘Personally, I’m not surprised the Prime Minister thinks it’s a good idea. He’s been doing it to the country for years.’

I, the noble Bo-Bo, the last of my species, take that to be a no. I slink out the back to once more urinate against a tree. It seems that, yet again, the species will have to wait. Right now, I’m just not in a position to save it.

I always hated the Boy Scouts, mostly because they made me sleep in the ditch. The ditch was dug around the edge of the tent to stop water coming in. As the youngest, newest and most incompetent recruit, I got to sleep on the edge of the tent and would soon end up in the ditch. It was uncomfortable, demeaning and—following heavy rain—gave fresh meaning to the term ‘floating off to sleep’.

I also had a problem with the flying fox (foolishly dangerous), the hygiene standards (appalling) and the fact that our holiday camp was shared with every young blowfly in the country. Maybe their parents didn’t want them hanging around home during the holidays either.

Naturally, I’d have rather stayed in my bedroom at home and got on with my reading, but my parents had determined that a week sleeping in a ditch might be of assistance in the

cause of achieving some sort of conventional manliness. It was, I guess, a last-ditch attempt.

Most baffling of all were the knots. I could never follow these intricate patterns of right over left, and left over right; of hitches and half pikes and slips. I would stick out my tongue and try to follow the diagram. Quickly, I’d find my tongue knotted while the rope lay limply in my hand: a metaphor for failed manhood if ever there was one.

And did one really need forty different knots in order to survive for a week on the coast? Certainly the explanations seemed a little far-fetched. The cat’s paw was good for attaching a rope to a hook, should one wish to achieve such a connection. The clove hitch was good for tying sacks, although the camp was sack-free, so who could be sure? And the bowline was excellent for tying around someone in a dramatic river rescue. (Just hold still in the raging torrent for three hours, while Richard, with his tongue stuck out, tries to follow the diagram. Just two hours and fifty-five minutes quicker, and I could have saved that boy’s life.)

Why have these nightmares come back to haunt me nearly four decades on? I blame the people next door. There’s a black-tie function on this weekend and I’ve bought tickets for myself and Batboy. I mention this to my neighbours, Jenny and Tom Neatwhistle, and Tom says: ‘I hope you’ll be wearing a proper hand-tied bow tie, and not one of those pre-done ones.’

I confess I’d planned to hire a couple of suits with built-in clip-ons, but the confession leaves my neighbour aghast. As with the Boy Scouts and their wretched knots, it seems there’s an issue of masculinity here.

‘Think of the moment,’ Tom confides, ‘late in the night, when people are starting to relax. You’ll undo your top button and then pull the ends of your bow tie. The knot will fall out, and the ends of the tie will dangle against your pressed white shirt. All the women will melt. They’ll know you are the real deal; that you are master of your own bow tie; that your fingers have a certain, ahem, dexterity.’

I enjoy this vivid portrait of myself and a table of fawning women. I enjoy it so much that I race out the next day and purchase real bow ties for myself and for the boy. At both David Jones and Gowings I notice they have three dozen pre-tied models, displayed beautifully, and a single choice of tie-your-own hidden on the bottom shelf. My hand hovers: why are the real-deals so unpopular? Could it be that they are harder to tie than one might think?

I reason with myself: silly old duffers have managed to do this for centuries; how hard can it be? We buy the ties and head home. Once there, we print off a diagram from the internet and set to work, both standing in front of the mirror. I discover that while I was completely hopeless at tying knots at age nine, I’m even worse now. Batboy, if this is possible, is even less skilled. Being seventeen, he also loses his temper in a more spectacular fashion.

The suave James Bond atmosphere we were hoping to create seems rather distant as we stomp in front of the mirror, swearing and sighing, petulantly scrunching our faces and declaring the whole thing ‘a bloody joke’.

For three nights we practise. Occasionally, through blind luck, we achieve the sort of granny knot with which a five-year-old might tie his or her shoes. The rest of the time we get nowhere.

We’re so desperate I finally remember being told about an old trick: the tie-substitution racket. You arrive wearing a clip-on, then whip out to the loo towards the end of the evening. You remove the clip-on and substitute it with an untied real-deal, just dangling it around your neck. The women, it is said, will assume it’s been real all the time and begin their incessant fawning.

It’s an evil idea but it may be our only hope. Either that or we’ll stitch ourselves into sacks and throw ourselves into a raging river, thus giving ourselves an excuse to not go. Anybody know how to do a clove hitch in a hurry?

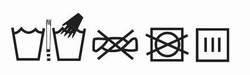

With all the effort going into fashion, couldn’t they focus a bit more on the care instruction labels? Does anybody understand what they mean, with their series of triangles, crosses and encircled washing machines? And do they have to be quite so alarming?

With particularly skimpy outfits, the care instruction label is now bigger than the garment. The garment must be hand-washed, in lukewarm distilled water, and then placed on a flat surface in the shade. Whatever you do, don’t squeeze it or wring it. And, certainly, never even mention the word ‘dryer’ in its presence. If you must speed up drying, you may blow on it gently, providing you haven’t recently eaten anything spicy. Once it’s dry, place your iron in the next room and simply walk past the doorway to that room, with the garment on a hanger, gently encouraging it to de-wrinkle.

The little diagrams on the care label are full of drama and intrigue, especially as one can only guess at their meanings. Does the picture of the choppy water mean you can only wear the garment sailing? What is this mysterious black hand being plunged into the choppy water from above, and this thing that looks like a croissant with a giant cross through it? And why, next to it on the label, is there a picture of a square window filled with prison bars? Has someone stolen a croissant, jumped into the ocean to escape, but then been caught and locked up? The care instructions on my new pants have more plot development than the average airport thriller.

Even worse are those garments that are beyond washing. They are so delicate, the manufacturer cannot begin to suggest how you might clean them. Even purchasing laundry powder while wearing them may invalidate your rights under consumer law. ‘Dry Clean Only’ is the label’s terse instruction.

Typically these garments are pure wool—maybe a suit or a pair of pants—and of course there’s no way wool can be exposed to water. Frankly, I find this a little hard to believe. Last time I looked, the sheep in the fields were not wearing raincoats. They were not marching around with a stockman holding a dainty little brolly over each animal. If the label is right, and wool shrinks when wet, why doesn’t it do it when it’s on the sheep’s back? Why haven’t we got a whole nation of size sixteen sheep waddling around in size fourteen fleeces? Why don’t they pant and wheeze while gambolling in the field, rather like a fat man over-optimistic in selecting his size of Levi’s?

I’m convinced it’s all a rip-off involving the dry cleaning industry and secret payments to the wool growers. ‘Just tell

them they can’t be washed,’ the dry-cleaners hiss, while handing over the cash to some bloke in an Akubra. ‘If they want them cleaned, tell them it’s got to be done

dry

.’

But here’s the thing: how can cleaning really be ‘dry’ anyway? Try taking a dry shower and see how clean you get. If your toddler, after using the loo, claimed to have dry-cleaned his hands, would you believe him? My hunch is that the big high-tech machines dominating the dry-cleaner’s store are just a cover. The whole thing is a scam. Out the back of the shop there’s some sort of creek. They have people out there, crouched over the water, beating your new Armani suit with a rock. Hours later, they bung it on a hanger, wrap it in plastic, and no one’s the wiser. ‘Thank you, wool industry.’

Surely it’s time we give up the fiction and admit that everything should be just thrown into the machine and thence into the dryer. That way the warning labels would be free for more useful messages.

Warnings labels such as: ‘You? In our stuff? You must be joking.’ Or: ‘Think again, lady.’ Or simply: ‘Ha, ha, ha.’

The trick is making the label match the product. On a Bonds T-shirt, for instance: ‘Arm ribbing may make upper arms appear fat.’ On a pair of pants from Jeans West: ‘Danger of self-wedgie in some models.’ Or on a dress in the window of a Paddington boutique: ‘May look sensational on the plastic hanger, but appalling on anyone heavier than a plastic hanger.’

Most of all, customers need to be warned about what happens once they leave the shop. ‘Bum may sag after moderate use.’ ‘Pants will look good when standing up in the change room but will later develop piano-accordion crotch.’ Or on a pair of $800 shoes: ‘Will stink after one outing.’

Maybe these sorts of messages are already there—hidden within the care instructions. Suddenly that picture of the crossed-out croissant doesn’t seem so obscure. ‘Eat more than one of these each year,’ the label is telling you, ‘and you’ll never fit into this garment ever again.’