Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (37 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

7.01Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

West Comes East

905-1266 AH

1500-1850 CE

1500-1850 CE

B

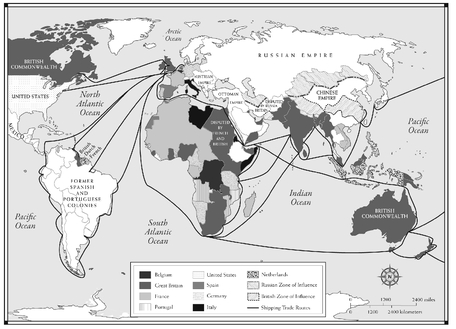

ETWEEN 1500 AND 1800 CE, western Europeans sailed pretty much all over the world and colonized pretty much everything. In some lands, they simply took possession, entirely supplanting the original inhabitants: North America and Australia suffered this fate, ending up as virtual extensions of Europe.

ETWEEN 1500 AND 1800 CE, western Europeans sailed pretty much all over the world and colonized pretty much everything. In some lands, they simply took possession, entirely supplanting the original inhabitants: North America and Australia suffered this fate, ending up as virtual extensions of Europe.

In other areas, they left the original inhabitants in place but moved in above them as a ruling elite in control of all-important resources. Some portion of the original population ended up as their servants or slaves while the rest went on living as best they could in constricted circumstances. Such was the fate of the people in most of South America and sub-Saharan Africa.

In some places, however—most notably China and the Islamic heartland—Europeans came up against well-organized, wealthy, technologically advanced societies seemingly quite able to hold their own, and here the interaction between newcomers and natives took a subtler course. The Islamic world presented a particularly complex psychosocial drama, first, because western Europeans had a tangled history with Muslims already, and second, because they started trickling into the Muslim world just a

s the three great Islamic empires were rising toward their peak of power and brilliance.

s the three great Islamic empires were rising toward their peak of power and brilliance.

WESTERN IMPERIALISM: THE GLOBAL REACH OF SEA POWER

Let’s be clear about one thing: the European penetration of the Muslim world never amounted to a clash of civilizations (to use a term coined in the 1990s). In this period of colonization, “European civilization” never went to war with “Islamic civilization,” and that’s one key to understanding all that followed. In fact, after 1500, western Europeans arrived in the eastern Islamic world mainly as traders. What could be less threatening? Trade is what people do

instead

of making war. Trade—why, it’s practically a synonym for peace!

instead

of making war. Trade—why, it’s practically a synonym for peace!

Nor did the Europeans come in great numbers. The first European expedition to reach India by sea was led by Portuguese aristocrat Vasco da Gama and consisted of four ships and a total crew of 171 men. They arrived at Calicut on the west coast of India in 1498 and asked the local Hindu ruler if they might set up a trading post along the coast there and do a little buying, maybe a little selling. The ruler said sure. Why wouldn’t he? If these strangers wanted to buy cloth, or raw cotton, or suga

r or whatever, why would he say no? His people had businesses to run! You don’t make money by refusing to sell your products.

r or whatever, why would he say no? His people had businesses to run! You don’t make money by refusing to sell your products.

The Europeans did encounter a flash of hostility from Muslims thereabouts a bit later, but the Muslims were interlopers themselves that far south and so the Portuguese got local Hindu support to build a little town and fort at a place called Goa. They had nothing very remarkable to trade, but they did have money to buy, and as the years went by more of them were coming along with more and more money to spend, as the gold of the Americas flooded the European economy. Goa became a permanent Portuguese implant in India.

Then more traders came along from other parts of western Europe. The French set up a “trading post” at Pondicherry and the British set up one at Madras.

1

The Dutch sailed by and looked in as well. These European communities started fighting among themselves for business advantages, but the Indians paid little notice. Why should they care who won? Babur and his descendents were just establishing the Moghul empire up north, and they were the big story of the time, much bigger than a few obscure traders building little forts along the coast. And so the sixteenth century passed without Europ

eans making much of an impact on the Islamic world.

1

The Dutch sailed by and looked in as well. These European communities started fighting among themselves for business advantages, but the Indians paid little notice. Why should they care who won? Babur and his descendents were just establishing the Moghul empire up north, and they were the big story of the time, much bigger than a few obscure traders building little forts along the coast. And so the sixteenth century passed without Europ

eans making much of an impact on the Islamic world.

Then again, not all Europeans came to the Muslim world as traders. Some came as business advisers or technical consultants. In 1598, a pair of English brothers, Robert and Anthony Sherley, found their way to Persia, which was well into its “golden age” under the greatest of the Safavid monarchs, Shah Abbas. The Englishmen said they came in peace with an interesting proposition for the Persian king: they wanted to sell him cannons and firearms and they could promise technical support to back up their products—they would have their people come in and train the Shah’s people in the new w

eapons, teach military strategy to go with them, plus how to fix the weapons if they broke, things like that.

eapons, teach military strategy to go with them, plus how to fix the weapons if they broke, things like that.

Shah Abbas liked what he heard. Safavid Persia lagged behind its neighbors in military technology. The Qizilbash didn’t like firearms; they were still fighting mostly with spears and swords and bows; this deficit had cost the Safavids the battle of Chaldiran, and now the hated Ottomans were trying to stop weapons shipments to Pe

rsia. Getting weapons and consultants from some distant, insignificant speck of an island west of Europe seemed like a perfect solution. The Englishmen knew their stuff, and a few of them from so far away couldn’t possibly do much harm, it seemed. And so it began: the practice of giving European advisers commanding positions in the Persian army.

rsia. Getting weapons and consultants from some distant, insignificant speck of an island west of Europe seemed like a perfect solution. The Englishmen knew their stuff, and a few of them from so far away couldn’t possibly do much harm, it seemed. And so it began: the practice of giving European advisers commanding positions in the Persian army.

It’s true, however, that not all interactions between westerners and Muslims were peaceful. The Ottoman Turks had been fighting with Christian Europeans for centuries; their western border was the frontier between the two worlds, and here the friction showed. Between battles, however, and even while pitched battles were raging in some places, a lot of trading was going on in other places, because this was not a World War II-type total-war situation. Battles were geographically contained. At the very moment that two armies were clashing one place, business-as-usual might well

be going on just a few miles away. The friction had an ideological dimension left over from the Crusades, to be sure—Christianity versus Islam—but in any practical sense the battles were outbursts of professional violence between monarchs over territory. Lots of Christians and Jews lived within the Ottoman empire, after all, and some of them were in the Ottoman armies, fighting for that side, not out of patriotic fervor for the House of Othman but because it was a job, and they needed the money. This kind of fighting certainly allowed for other people to be going back and forth, buying and selling.

be going on just a few miles away. The friction had an ideological dimension left over from the Crusades, to be sure—Christianity versus Islam—but in any practical sense the battles were outbursts of professional violence between monarchs over territory. Lots of Christians and Jews lived within the Ottoman empire, after all, and some of them were in the Ottoman armies, fighting for that side, not out of patriotic fervor for the House of Othman but because it was a job, and they needed the money. This kind of fighting certainly allowed for other people to be going back and forth, buying and selling.

By the seventeenth century, it wasn’t just Venetians but also French, English, German, Dutch, and other European traders who were traveling into the Muslim world armed not with gold but with guns. These businessmen contributed to a process that slowly and inexorably transformed the mighty Ottoman Empire into the lumbering monstrosity that Europeans called the Sick Man of Europe, or sometimes—more gently but in some ways even more condescendingly—“the Eastern question.” The process was so slow, however, and so pervasive and so complex that it was hard for anyone going through the

history of it all day by day to make a connection between the European encroachment and the burgeoning decay.

history of it all day by day to make a connection between the European encroachment and the burgeoning decay.

The first thing to note about the process is what

didn’t

happen. The Ottoman Empire did not go down in flames to conquering armies. Long after the empire was totally moribund, long after it was little mo

re than a virtual carcass for vultures to pick over, the Ottomans could still muster damaging military strength.

didn’t

happen. The Ottoman Empire did not go down in flames to conquering armies. Long after the empire was totally moribund, long after it was little mo

re than a virtual carcass for vultures to pick over, the Ottomans could still muster damaging military strength.

Historians identify two seminal military defeats that spelled the beginning of the end for the Ottomans, though both went more or less unnoticed by the Turks at the time. One was the battle of Lepanto, which took place in 1571. In this naval engagement, the Venetians and their allies destroyed virtually the entire Ottoman Mediterranean fleet. In Europe, the battle was hailed as a thrilling sign that the heathen Turk was finally, finally going down.

In Istanbul, however, the grand vizier compared the loss of the fleet to the shaving of a man’s beard: it would only make the new beard grow in thicker. Indeed, within one year, the Ottomans replaced the whole lost fleet with an even bigger and more modern fleet, featuring eight of the largest ships ever to ply the Mediterranean. Within six months after

that

, the Ottomans won back the eastern Mediterranean, conquered Cyprus, and began to harass Sicily. Small wonder that contemporary Ottoman analysts didn’t see the battle of Lepanto as any big turning point at the time. It would

take at least another century before European naval dominance would become fully evident and the significance of that dominance unmistakable.

that

, the Ottomans won back the eastern Mediterranean, conquered Cyprus, and began to harass Sicily. Small wonder that contemporary Ottoman analysts didn’t see the battle of Lepanto as any big turning point at the time. It would

take at least another century before European naval dominance would become fully evident and the significance of that dominance unmistakable.

The other seminal military event took place a bit earlier with a follow-up much later. The earlier bracket was Suleiman the Magnificent’s failure to take Vienna. Ottoman forces had never stopped pushing steadily west, and in 1529 they reached the gates of Vienna, but the sultan set siege to the famous Austrian city too late in the season. With winter coming on, he decided to let Vienna go this time and conquer it the next time around. But there was no next time for Suleiman, because other issues cropped up and he got distracted—the empire was so big, after all, and its borders so long, that

distractions were constantly sprouting up on those borders

somewhere

. The sultan never made another attempt on Vienna but his contemporaries saw no sign of weakness in this. “Conquer Vienna” remained on his to-do list always; it’s just that the man was

busy

. He was fighting and winning other battles, and his rule was so successful that only a blithering idiot would have suggested that the Ottomans were in decline in his day just because they had not taken Vienna. It wasn’t a military defeat, after all, just a failure to score the usual crushing victory.

distractions were constantly sprouting up on those borders

somewhere

. The sultan never made another attempt on Vienna but his contemporaries saw no sign of weakness in this. “Conquer Vienna” remained on his to-do list always; it’s just that the man was

busy

. He was fighting and winning other battles, and his rule was so successful that only a blithering idiot would have suggested that the Ottomans were in decline in his day just because they had not taken Vienna. It wasn’t a military defeat, after all, just a failure to score the usual crushing victory.

And yet historians looking back can see quite clearly that Suleiman’s failure to take Vienna marked a watershed. At that moment the empire had reached its greatest extent. After that moment, it was no longer expanding. This was less than obvious at the time because the empire was still fighting someone somewhere all the time, and the news from the battlefield was often good. Maybe the Ottomans were losing battles here and there, but they were also winning battles here and there. Were they losing more than they were winning? Were they losing the big ones and winning only the l

ittle ones? That was the real question, and the answer was yes, but that was hard to gauge for people swimming through the historical moment. How does one weigh the significance of a battle? Some people raised alarmist cries, but some people always do. After all, in 1600, the empire certainly was not shrinking.

ittle ones? That was the real question, and the answer was yes, but that was hard to gauge for people swimming through the historical moment. How does one weigh the significance of a battle? Some people raised alarmist cries, but some people always do. After all, in 1600, the empire certainly was not shrinking.

Unfortunately, however, not shrinking was not good enough for the Ottoman Empire. In truth, this empire was built on the

premise

of permanent expansion. It needed a constant and generally successful war on its borders for all of its complicated internal mechanisms to work.

premise

of permanent expansion. It needed a constant and generally successful war on its borders for all of its complicated internal mechanisms to work.

First of all, expansion was a source of revenue, which the empire could ill afford to lose.

Second, war served as a safety valve, which vented all internal pressures outward. For example, peasants who were forced off the land for one reason or another didn’t hang around hungry and hopeless, turning into a surly rabble. They could always join the army, go on a campaign, score some booty, and then come home and start a little business. . . .

Once expansion stopped, however, all those pressures began to press inward. Those who could no longer make a living off the land for any reason now drifted to the cities. Even if they had a skill, they might not be able to ply it. The guilds controlled all manufacturing and they could absorb only so many new members. A good many of the drifters ended up unemployed and disgruntled. And there were lots of other little consequences like this, generated by no longer expanding.

Third, the classic

devshirme

depended on the constant conquest of new territories out of which “slaves” could be drafted for the institutes that produced the empire’s elite. The

janissary

had originally labored under one important restriction: they were not allowed to marry and produce heirs, a device designed to keep new blood flowing into the administ

ration. But once the expansion stopped, the devshirme began to stagnate. And then the janissaries began to marry. And then they did what people do for their children: swing their clout to get the kids the best possible educational and employment opportunities. It was perfectly natural, but it did mean the janissaries encrusted into a permanent, hereditary elite, which reduced the vigor of the empire because it meant the experts and specialists who ran the empire were no longer drawn exclusively from those who showed early promise but also included dullards with rich and important parents.

devshirme

depended on the constant conquest of new territories out of which “slaves” could be drafted for the institutes that produced the empire’s elite. The

janissary

had originally labored under one important restriction: they were not allowed to marry and produce heirs, a device designed to keep new blood flowing into the administ

ration. But once the expansion stopped, the devshirme began to stagnate. And then the janissaries began to marry. And then they did what people do for their children: swing their clout to get the kids the best possible educational and employment opportunities. It was perfectly natural, but it did mean the janissaries encrusted into a permanent, hereditary elite, which reduced the vigor of the empire because it meant the experts and specialists who ran the empire were no longer drawn exclusively from those who showed early promise but also included dullards with rich and important parents.

No one linked these stagnations to the fact that Suleiman had failed to conquer Vienna decades ago. How could they? The consequences were so distantly and so indirectly related to their causes that for the general public they registered merely as some sort of indefinable social malaise that was hard to explain, the sort of thing that makes religious conservatives rail about the moral fabric of society and the importance of restoring old-fashioned values like discipline and respect for elders.

Then came the follow-up to Suleiman’s failure. In 1683, the Ottomans tried again to take Vienna and they failed again, just as they had 154 years earlier, but this time they were routed by a coalition of European forces. Technically this second battle for Vienna was also merely a failure to score a victory, but the Ottoman elite knew they had been trounced and something had gone very wrong.

Other books

As I Rode by Granard Moat by Benedict Kiely

Return to Vienna by Nancy Buckingham

Sword of the Gods: The Chosen One by Erishkigal, Anna

A Temporal Trust (The Temporal Book 2) by Martin, CJ

Holidays With the Walker Brothers by Nicole Edwards

Daisy and the Duke by Janice Maynard

Touched by Darkness (Young Creator Trilogy) by Christiane Shoenhair

Stealing Luca's Heart by Lyons, Ellie

Cold in the Shadows 5 by Toni Anderson