Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (53 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

10.81Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Other narratives continued to play out, however, beneath the surface of the bipolar Cold War struggle, including the submerged narrative of Islam as a world-historical event. The hunger for independence, which

had built up during the war years among virtually all colonized people, both Muslim and non-Muslim, now hit the breaking point. In Egypt, rebellion started brewing among army officers. In China, Mao’s communist insurgency began to move against Chiang Kai-shek, widely seen as a Western puppet. In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh, who had come back from thirty years of exile to organize the Viet Minh, attacked the French. In Indonesia, Sukarno declared his country independent from the Dutch. All over the world, national liberation movements were springing up like weeds, and the ones in Muslim countries were m

uch like the ones in non-Muslim countries: whatever else might be happening, the Islamic narrative was now intertwined with a narrative Muslims shared with others.

had built up during the war years among virtually all colonized people, both Muslim and non-Muslim, now hit the breaking point. In Egypt, rebellion started brewing among army officers. In China, Mao’s communist insurgency began to move against Chiang Kai-shek, widely seen as a Western puppet. In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh, who had come back from thirty years of exile to organize the Viet Minh, attacked the French. In Indonesia, Sukarno declared his country independent from the Dutch. All over the world, national liberation movements were springing up like weeds, and the ones in Muslim countries were m

uch like the ones in non-Muslim countries: whatever else might be happening, the Islamic narrative was now intertwined with a narrative Muslims shared with others.

Geographically, many of the “nations” that the liberation movements strove to liberate were defined by borders the imperialist powers had drawn: so even in their struggle for liberation they were playing out a story set in motion by Europeans. In sub-Saharan Africa, what the king of Belgium had managed to conquer became Congo (later renamed Zaire). What the Germans had conquered became Cameroon, what the British had conquered in East Africa, Kenya. A label such as “Nigeria” referred to an area inhabited by over two hundred ethnic groups speaking more than five hundred languages, many

of them mutually unintelligible, but the world was now organized into countries, so this, too, became “a country,” its shape and size reflecting the outcome of some long-ago competition among colonizing Europeans.

of them mutually unintelligible, but the world was now organized into countries, so this, too, became “a country,” its shape and size reflecting the outcome of some long-ago competition among colonizing Europeans.

In North Africa, national liberators accepted the reality of Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya as countries, each one spawning a national liberation movement of its own. All three movements eventually succeeded, but at great cost. Algeria’s eight-year war of independence from France claimed over a million Algerian lives, out of a starting population of fewer than 9 million, a staggering conflict.

1

1

Issues inherited from the days of Muslim hegemony continued to echo here and there. The persistence of the Muslim narrative manifested most dramatically in the subcontinent of India, the biggest full-fledged colony to gain independence. Even before the war, as this nascent country struggled to rid itself of the British, a subnational movement had developed within the grand national movement: a demand by the Muslim minority for a separate country. At the exact moment that India was born (August 15, 1947) so was the brand-new two-part country of Pakistan, hanging

like saddlebags east and west of India. The partition of the subcontinent sent tidal waves of frightened refugees across new borders to the supposed shelter of their coreligionists. In the tumult, hundreds of thousands were slaughtered within weeks, and countless more rendered homeless, yet even this mayhem failed to settle the questions raised by “the partition.” Kashmir, for example, remained in play, for it had a Hindu monarch but a predominantly Muslim population. Which then should it be part of, India or Pakistan? The British decided to wait and see how things shook out. Kashmir is still shaking.

like saddlebags east and west of India. The partition of the subcontinent sent tidal waves of frightened refugees across new borders to the supposed shelter of their coreligionists. In the tumult, hundreds of thousands were slaughtered within weeks, and countless more rendered homeless, yet even this mayhem failed to settle the questions raised by “the partition.” Kashmir, for example, remained in play, for it had a Hindu monarch but a predominantly Muslim population. Which then should it be part of, India or Pakistan? The British decided to wait and see how things shook out. Kashmir is still shaking.

It was not only decolonization that came to a head after World War II, but “nation-statism.” It’s easy to forget that the organization of the world into countries is less than a century old, but in fact this process was not fully completed until this period. Between 1945 and 1975, some one hundred new countries were born, and every inch of earth finally belonged to some nation-state or other.

2

2

Unfortunately, the ideology of “nationalism” and the reality of “nation-statism” matched up only approximately if at all. Many supposed countries contained stifled sub-countries within their borders, ethnic minorities who felt they ought to be separate and “self-governing.” In many cases, people on two sides of a border felt like they ought to be part of the same nation. Where Syria, Iraq, and Turkey came together, for example, their borders trisected a contiguous area inhabited by a people who spoke neither Arabic nor Turkish but Kurdish, a distant variant of Persian, and these Kurds na

turally felt like members of some single nation that was “none of the above.”

turally felt like members of some single nation that was “none of the above.”

In some places, even the separate existence of given countries remained open to question. Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan—these were still congealing. Their borders existed, they had separate governments, but did their people really think of themselves as

different nations

? Not clear.

different nations

? Not clear.

In the Arab world, ever since Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, the watchword had been self-rule, but this tricky concept presumed some definition of a collective “self ” accepted by all its supposed members. Nationalists throughout Arab-inhabited lands were trying hard to consolidate discrete states: Libya, Tunisia, Syria, even Egypt . . . but the question always came up: who was the bigger collective self? Was there “really” a Syrian nation, given that the Syria seen on maps was created by Europeans? Could there be such a thing as Jordanian nationalism? Was it true that people

living in Iraq were ruling themselves so long as their ruler spoke Arabic?

living in Iraq were ruling themselves so long as their ruler spoke Arabic?

The most problematic single territory for the competing claims of nationalism versus nation-statism was Palestine, soon to be known as Israel. Before and during World War II, the Nazis’ genocidal attempt to exterminate the Jews of Europe confirmed the worst fears of Zionists and gave their argument for a sovereign Jewish homeland overwhelming moral weight, especially since the Nazis were not the only anti-Semites in Europe, only the most extreme. The fascists of Italy visited horrors upon Italian Jews, the French puppet government set up by the Germans hunted down French Jews f

or their Nazi masters, the Poles and other Eastern Europeans collaborated enthusiastically in operating death camps, Great Britain had its share of anti-Semites, Spain, Belgium—no part of Europe could honestly claim innocence of the crime committed against the Jews in this period. Millions of Jews were trapped in Europe and perished there. All who could get away escaped in whatever direction lay open. Boatloads of Jewish refugees ended up drifting over the world’s seas, looking for places to land. A few were able to make their way to the United States and resettle there, but even the United States imposed stric

t quotas on Jewish immigration, presumably because a single country could absorb only so many immigrants of any one group; but just perhaps some anti-Semitism was mixed into that policy as well.

or their Nazi masters, the Poles and other Eastern Europeans collaborated enthusiastically in operating death camps, Great Britain had its share of anti-Semites, Spain, Belgium—no part of Europe could honestly claim innocence of the crime committed against the Jews in this period. Millions of Jews were trapped in Europe and perished there. All who could get away escaped in whatever direction lay open. Boatloads of Jewish refugees ended up drifting over the world’s seas, looking for places to land. A few were able to make their way to the United States and resettle there, but even the United States imposed stric

t quotas on Jewish immigration, presumably because a single country could absorb only so many immigrants of any one group; but just perhaps some anti-Semitism was mixed into that policy as well.

The one place where the refugees

could

land was Palestine. There, earlier immigrants had bought land, planted settlements, and developed some infrastructure of support. Toward that slender hope of safety, therefore, the refugees headed, overcoming heroic hardships to begin building a new nation in an ancient land inhabited by their ancestors. Such was the shape of the story from the Jewish side.

could

land was Palestine. There, earlier immigrants had bought land, planted settlements, and developed some infrastructure of support. Toward that slender hope of safety, therefore, the refugees headed, overcoming heroic hardships to begin building a new nation in an ancient land inhabited by their ancestors. Such was the shape of the story from the Jewish side.

From the Arab side, the story looked different. The Arabs had long been living under two layers of domination by outsiders, the first layer being the Turks, the next the Turks’ European bosses. Then, in the wake of World War I, amidst all the rhetoric about “self-rule” and all the hope aroused by Wilson’s Fourteen Points, their land was flooded by new settlers from Europe, whose slogan was said to be “a land without a people for a people without a land”

3

—an alarming slogan for people living in the “land without a people.”

3

—an alarming slogan for people living in the “land without a people.”

The new European immigrants didn’t seize land by force; they bought the land they settled; but they bought it mostly from absentee landlords, so they ended up living among landless peasants who felt doubly dispossessed by the aliens crowding in among them. What happe

ned just before and during World War II in Palestine resembled what happened earlier in Algeria when French immigrants bought up much of the land and planted a parallel economy there, rendering the original inhabitants irrelevant. By 1945, the Jewish population of Palestine almost equaled the Arab population. If one were to translate that influx of newcomers to the American context, it would be as if 150 million refugees flooded in within a decade. How could that not lead to turmoil?

ned just before and during World War II in Palestine resembled what happened earlier in Algeria when French immigrants bought up much of the land and planted a parallel economy there, rendering the original inhabitants irrelevant. By 1945, the Jewish population of Palestine almost equaled the Arab population. If one were to translate that influx of newcomers to the American context, it would be as if 150 million refugees flooded in within a decade. How could that not lead to turmoil?

In the context of the European narrative, the Jews were victims. In the context of the Arab narrative, they were colonizers with much the same attitudes toward the indigenous population as their fellow Europeans. As early as 1862, a German Zionist, Moses Hess, had drummed up support for political Zionism by proposing that “the state the Jews would establish in the heart of the Middle East would serve Western imperial interests and at the same time help bring Western civilization to the backward East.”

4

The seminal Zionist Theodor Herzl wrote that a Jewish state in Palestine would “

form a portion of the rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.”

5

In 1914, Chaim Weitzman wrote a letter to the Manchester

Guardian

stating that if a Jewish settlement could be established in Palestine “we could have in twenty to thirty years a million Jews out there. . . . They would develop the country, bring back civilization to it and form a very effective guard for the Suez Canal.”

6

Arabs who saw the Zionist project as European colonialism in thin disguise were not inventing a fantasy out of whole cloth: Zionists saw the project that way too, or a

t least represented it as such to the imperialist powers whose support they needed.

4

The seminal Zionist Theodor Herzl wrote that a Jewish state in Palestine would “

form a portion of the rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.”

5

In 1914, Chaim Weitzman wrote a letter to the Manchester

Guardian

stating that if a Jewish settlement could be established in Palestine “we could have in twenty to thirty years a million Jews out there. . . . They would develop the country, bring back civilization to it and form a very effective guard for the Suez Canal.”

6

Arabs who saw the Zionist project as European colonialism in thin disguise were not inventing a fantasy out of whole cloth: Zionists saw the project that way too, or a

t least represented it as such to the imperialist powers whose support they needed.

In 1936, strikes and riots broke out among the Arabs of Palestine, serving notice that the situation was spiraling out of control. In a clumsy effort to placate the Arabs, Great Britain issued an order limiting further Jewish immigration to Palestine, but this order came in 1939, with World War II about to break out and the horrors of Nazism fully manifest to European Jews: there was no chance that Jewish refugees would comply with the British order; it would have been suicidal. Instead, militant organizations sprang up among the would-be Jewish settlers, and since they were a disp

ossessed few fighting the world-straddling British Empire, some of these militant Jewish groups resorted to the archetypal strategy of the scattered weak against the well-organized mighty: hit and run raids, sabotage, random assassinations, bombings of places frequented by civilians—in s

hort, terrorism. In 1946, the underground Jewish militant group Haganah bombed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing ninety-one ordinary civilians, the most destructive single act of terrorism until 1988, when Libyan terrorists brought down a civilian airliner, Pan Am Flight 103, over Scotland, killing 270.

ossessed few fighting the world-straddling British Empire, some of these militant Jewish groups resorted to the archetypal strategy of the scattered weak against the well-organized mighty: hit and run raids, sabotage, random assassinations, bombings of places frequented by civilians—in s

hort, terrorism. In 1946, the underground Jewish militant group Haganah bombed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing ninety-one ordinary civilians, the most destructive single act of terrorism until 1988, when Libyan terrorists brought down a civilian airliner, Pan Am Flight 103, over Scotland, killing 270.

The horrors of Nazism proved the Jewish need for a secure place of refuge, but Jews did not come to Palestine pleading for refuge so much as claiming entitlement. They insisted they were not begging for a favor but coming

home

to land that was

theirs by right

. They based their claim on the fact that their ancestors had lived there until the year 135 CE and that even in diaspora they had never abandoned hope of returning. “Next year in Jerusalem” was part of the Passover service, a key cultural and religious rite in Judaism. According to Jewish doctrine, God had given the disputed l

and to the Hebrews and their descendants as part of His covenant with Abraham. Arabs, of course, were not persuaded by a religious doctrine that assigned the land they inhabited to another people, especially since the religion was not theirs.

home

to land that was

theirs by right

. They based their claim on the fact that their ancestors had lived there until the year 135 CE and that even in diaspora they had never abandoned hope of returning. “Next year in Jerusalem” was part of the Passover service, a key cultural and religious rite in Judaism. According to Jewish doctrine, God had given the disputed l

and to the Hebrews and their descendants as part of His covenant with Abraham. Arabs, of course, were not persuaded by a religious doctrine that assigned the land they inhabited to another people, especially since the religion was not theirs.

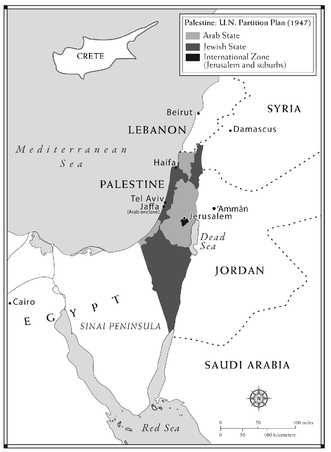

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States led efforts to create new political mechanisms for keeping the peace, one of which was the United Nations. Palestine was just the sort of issue the United Nations was designed to resolve. In 1947, therefore, the United Nations crafted a proposal to end the quarrel by dividing the disputed territory and creating two new nations. Each competing party would get three patches of curiously interlocking land, and Jerusalem would be a separate international city belonging to neither side. The total territories of the proposed new nations

, Israel and Palestine, would be roughly equal. Essentially, the United Nations was saying, “It doesn’t matter who’s right or wrong; let’s just divide the land and move on.” This is the sort of solution that adults typically impose on quarreling children.

, Israel and Palestine, would be roughly equal. Essentially, the United Nations was saying, “It doesn’t matter who’s right or wrong; let’s just divide the land and move on.” This is the sort of solution that adults typically impose on quarreling children.

But Arabs could not agree that both sides had a point and that the truth lay somewhere in the middle: they felt that a European solution was being imposed on them for a European problem, or more precisely that Arabs were being asked to sacrifice their land as compensation for a crime visited by Europeans on Europeans. The Arabs of surrounding lands sympathized with their fellows in Palestine and saw their point; the world at large did not. When the matter was put to a vote in the General Assembly of the United Nations, the vast majority of non-Muslim countries voted yes to partition.

Most Arabs had no personal stake in the actual issue: the birth of Israel would not strip an Iraqi farmer of his land or keep

some Moroccan shop-keeper from prospering in his business—yet most Arabs and indeed most Muslims could wax passionate about who got Palestine. Why? Because the emergence of Israel had emblematic meaning for them. It meant that Arabs (and Muslims generally) had no power, that imperialists could take any part of their territory, and that no one outside the Muslim world would side with them against a patent injustice. The existence of Israel signified European dominance over Muslims, Arab and non-Arab, and over the people of Asia and Africa generally. That’s how it looked from almost any point betw

een the Indus and Istanbul.

some Moroccan shop-keeper from prospering in his business—yet most Arabs and indeed most Muslims could wax passionate about who got Palestine. Why? Because the emergence of Israel had emblematic meaning for them. It meant that Arabs (and Muslims generally) had no power, that imperialists could take any part of their territory, and that no one outside the Muslim world would side with them against a patent injustice. The existence of Israel signified European dominance over Muslims, Arab and non-Arab, and over the people of Asia and Africa generally. That’s how it looked from almost any point betw

een the Indus and Istanbul.

Other books

iPad Pro for Beginners: The Unofficial Guide to Using the iPad Pro by Scott La Counte

Shadow's End (Light & Shadow) by Katson, Moira

Even Though I Don't Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Riggs Crossing by Michelle Heeter

Charms for the Easy Life by Kaye Gibbons

Juice: Part Two (Juice #2) by Victoria Starke

Corridors of Death by Ruth Dudley Edwards

Lily and the Beast (Lily and the Beast #1) by Amelia Jayne

Ekleipsis by Pordlaw LaRue

From a Dead Sleep by Daly, John A.