Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (49 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

8.91Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Turkish nationalist intellectuals began to argue that Christian minorities, especially the Armenians, were a privileged aristocracy in Turkey, inherant internal enemies of the state, in league with the Russians

, in league with the western Europeans, in league with the breakaway Slavic territories of Eastern Europe.

, in league with the western Europeans, in league with the breakaway Slavic territories of Eastern Europe.

This new generation of Turkish nationalists said the nation superseded all smaller identities and suggested that the national “soul” might be vested in some single colossal personality, an idea that came straight from the German nationalist philosophers. The writer Ziya Gökalp declared that except for heroes and geniuses, individuals had no value. He urged his fellow Turks never to speak of “rights.” There were no rights, he said, only duties: the duty to hear the voice of the nation and follow its demands.

7

7

Trouble for the empire tended to confer glamour upon such militaristic nationalism. And trouble did keep coming. It had been coming for a long, long time. Bulgaria wrenched free. Bosnia and Herzegovina left the Ottoman fold to be annexed by the Habsurgs into their Austro-Hungarian empire. About a million Muslims, forced into exile by these changes, streamed into Anatolia looking for new homes in the dying, dysfunctional, and already-crowded empire. Then the Ottomans lost Crete. Nearly half the population of that island were Muslims, nearly all of whom migrated east. All this social

dislocation generated a pervasive atmosphere of free-floating anxiety.

dislocation generated a pervasive atmosphere of free-floating anxiety.

Amid the uproar, nationalism began heating up among other groups. Arab nationalism began to bubble, for one. And after all the horrors they had suffered at the hands of their fellow Turks, Armenian activists too declared a need and right to carve out a sovereign nation-state of Armenia. These were exactly the same nationalist impulses stirring among so many self-identified nationalities in eastern Europe at this time.

In 1912, a war in the Balkans stripped the empire of Albania, of Macedonia, of its last European holdings outside Istanbul, a military defeat that triggered a final spasm of anxiety, resentment, and confusion in Asia Minor. Turmoil like this favors the most tightly organized group, whatever its popular support may be; the Bolsheviks proved as much in Russia five years later. In Istanbul, the most tightly organized group just then was the ultranationalist Committee for Union and Progress. On January 23, 1913, the CUP seized control in a coup d’etat, assassinated the incumbent

vizier, deposed the last Ottoman sultan, ousted all other leaders from the government, declared all other parties illegal, and turned Ottoman Turkey into a one-party state. A triumverate of men emerged as spearheads of this single

party: Talaat Pasha, Enver Pasha, and Djemal Pasha, and it was these “three Pashas” who happened to be ruling the truncated remains of the Ottoman empire in 1914, when the long-anticipated European civil war broke out.

vizier, deposed the last Ottoman sultan, ousted all other leaders from the government, declared all other parties illegal, and turned Ottoman Turkey into a one-party state. A triumverate of men emerged as spearheads of this single

party: Talaat Pasha, Enver Pasha, and Djemal Pasha, and it was these “three Pashas” who happened to be ruling the truncated remains of the Ottoman empire in 1914, when the long-anticipated European civil war broke out.

In Europe, it was called the Great War; to the Middle World, however, it looked like a European civil war at first: Germany and Austria lined up against France, Britain, and Russia, and most other European countries soon jumped in or got dragged in unwillingly.

Muslims had no dog in this fight, but CUP leaders thought that they might reap big benefits by joining the winning side before the fighting ended. Like most people, they assumed the war would last no more than a few months, because the great powers of Europe had been stockpiling “advanced” technological weapons for decades, fearsome firepower against which nobody and nothing could possibly stand for long, so it looked as if the war could only be a sudden bloody shootout from which the first to fire and the last to run out of ammo would emerge as winner.

CUP strategists decided this winner would be Germany. After all, Germany was the continent’s mightiest industrial power, it had already squashed the French, and it held central Europe, which meant that it could move troops and war machines through its own territory on its superb rail network to every battlefront. Besides, by siding with Germany, the Turks would be fighting two of its enduring foes, Russia and Great Britain.

Eight months into the war, with Russian troops already threatening the northern border of their empire, CUP leaders ordered the infamous Deportation Act. Officially, this order was supposed to “relocate” the Armenians living near Russia to sites deeper within the empire where they wouldn’t be able to make common cause with the Russians. To this day, the Turkish government insists that the Deportation Act was purely a security measure necessitated by war. They admit that, yes, some killing did take place, but a civil war was raging, so what can you expect, and besides the violence went both

ways—such is the official position from which no Turkish government has yet budged.

ways—such is the official position from which no Turkish government has yet budged.

And the fact is, there

was

a war on, the Russian

were

coming, some Armenians

were

collaborating with the Russians, some Armenians

did

kill some Turks, and some of the violence of 1915 early on was, it seems, a continuation of that unstructured hatred that burst out in the 1890s a

s pogroms and ethnic cleansing. (The United Nations defines “ethnic cleansing” as the attempt to enforce ethnic homogeneity in a given territory by driving out or killing unwanted groups, often by committing atrocities that frighten them in into fleeing.)

was

a war on, the Russian

were

coming, some Armenians

were

collaborating with the Russians, some Armenians

did

kill some Turks, and some of the violence of 1915 early on was, it seems, a continuation of that unstructured hatred that burst out in the 1890s a

s pogroms and ethnic cleansing. (The United Nations defines “ethnic cleansing” as the attempt to enforce ethnic homogeneity in a given territory by driving out or killing unwanted groups, often by committing atrocities that frighten them in into fleeing.)

Outside of Turkey, however, few scholars doubt that in 1915 something much worse than ethnic cleansing took place, reprehensible as that alone would have been. The Deportation Act was the beginning of an organized attempt by Talaat Pasha, and perhaps Enver Pasha, and possibly other nameless leaders in the anonymous secret core of the CUP, to exterminate the Armenians, as a people—not just from Asia Minor or Turkish-designated areas but from the very Earth. Those who were being “relocated” were actually force-marched and brutalized to death; it was, in short, attempted genocide (define

d by the United Nations as any attempt to erase a targeted ethnic group not just from a given area but altogether). The exact toll remains a matter of dispute but it exceeded a million. Talaat Pasha presided over this horror as minister of the Interior and then prime minister of Ottoman Turkey, a post he held until the end of World War I.

d by the United Nations as any attempt to erase a targeted ethnic group not just from a given area but altogether). The exact toll remains a matter of dispute but it exceeded a million. Talaat Pasha presided over this horror as minister of the Interior and then prime minister of Ottoman Turkey, a post he held until the end of World War I.

Turkish revisionist historian Taner Akçam quotes a doctor affiliated with the CUP at the time of the massacres explaining that, “Your nationality comes before everything else. . . . The Armenians of the East were so excited against us that if they remained in their land, not a single Turk, not a single Muslim could stay alive. . . . Thus, I told myself: oh, Dr. Rechid, there are only two options. Either they will cleanse the Turks or they will be cleansed by the Turks. I could not remain undecided between these two alternatives. My Turkishness overcame my condition as a doctor. I told myself:

‘instead of being exterminated by them, we should exterminate them.’”

8

‘instead of being exterminated by them, we should exterminate them.’”

8

But the CUP had thoroughly miscalculated. For one thing, the war did not end quickly. Instead of one big blast of offensive destruction, the western-European theater ground down to a bizarre defensive struggle between armies of millions, lined up for hundreds of miles, in trenches separated by desolate killing fields that were littered with explosives and barbed wire. Battles kept breaking out along these lines, and sometimes they killed tens of thousands in the course of a few hours but the territory won or lost in these battles was often measurable in mere inches. This was the Eu

ropean theater.

ropean theater.

To break the deadlock, the British decide to attack the Axis powers from behind, by coming at them through Asia Minor. Doing this required first crippling the Ottomans. The Allies landed troops on the peninsula of Gallipoli, from which they hoped to storm Istanbul, but this assault failed and Allied troops were massacred.

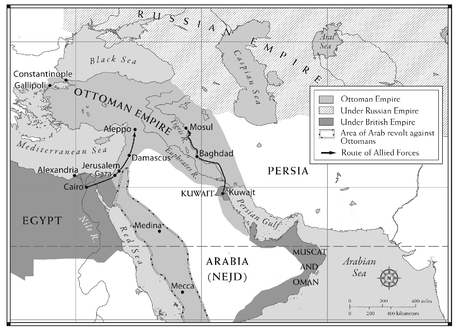

Meanwhile, the British were already busy trying to exploit another Ottoman weakness: rebellion was percolating throughout the empire’s Arab provinces, stemming from many sources. Nationalist movements sought Arab independence from Turks. Ancient tribal alignments chaffed at Ottoman administrative rules. Various powerful Arab families sought to establish themselves as sovereign local dynasties. In all this discontent, the British smelled an opportunity.

Among the dynastic contenders, two families stood out: the house of Ibn Saud, which was still allied with Wahhabi clerics, and the Hashimite family, which ruled Mecca, the spiritual center of Islam.

The Saudi-Wahhabi realm had shrunk down to a Bedouin tribal state in central Arabia but was still headed by a direct descendant of that ancestral eighteenth-century Saudi chieftain Mohammed Ibn Saud, the one who had struck a deal with the radically conservative cleric Ibn Wahhab. Over the decades, the two men’s families had intermarried extensively; the Saudi sheikh was now the religious head of the Wahhabi establishment, and Ibn Wahhab’s descendents still constituted the leading ulama of Saudi-ruled territories. British agents dispatched by the Anglo-Indian foreign office visited the Saudi c

hief, looking to cut a deal. They did what they could to excite his ambitions and offered him money and arms to attack the Ottomans. Ibn Saud responded cautiously but the interaction gave him good reason to believe that he would be rewarded after the war for any damage he could do to the Turks.

hief, looking to cut a deal. They did what they could to excite his ambitions and offered him money and arms to attack the Ottomans. Ibn Saud responded cautiously but the interaction gave him good reason to believe that he would be rewarded after the war for any damage he could do to the Turks.

The Hashimite patriarch was named Hussein Ibn Ali. He was caretaker of the Ka’ba, Islam’s holiest shrine, and he was known by the title of Sharif, which meant he was descended from the Prophet’s own clan, the Banu Hashim. Remember that the ninth-century revolutionaries who had brought the Abbasids to power called themselves the Hashimites: the name had an ancient and revered lineage and now a family by this name was ruling again in Mecca.

But Mecca was not enough for Sharif Hussein. He dreamed of an Arab kingdom stretching from Mesopotamia to the Arabian Sea, and

he thought the British might help him forge it. The British gladly let him think they could and would. They sent a flamboyant military intelligence officer to work with him, a one-time archeologist named Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence, who spoke Arabic and liked to dress in Bedouin tribal dress, a practice that eventually earned him the nickname “Lawrence of Arabia.”

he thought the British might help him forge it. The British gladly let him think they could and would. They sent a flamboyant military intelligence officer to work with him, a one-time archeologist named Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence, who spoke Arabic and liked to dress in Bedouin tribal dress, a practice that eventually earned him the nickname “Lawrence of Arabia.”

WORLD WAR I AND THE ARAB REVOLT

Looking back, it’s easy to see what a pot of trouble the British were mixing up here. The Hashimites and the Saudis were the two strongest tribal groups in the Arabian peninsula; both hoped to break the Ottoman hold on Arabia, and each saw the other as its deadly rival. The British were sending agents into both camps, making promises to both families, and leading both to believe that the British would help them establish their own kingdom in roughly the

same

territory, if only they would fight the Ottomans. The British didn’t actually care which of the tw

o ruled this region: they just wanted immediate help undermining Ottoman power, so they could beat the Germans back home.

same

territory, if only they would fight the Ottomans. The British didn’t actually care which of the tw

o ruled this region: they just wanted immediate help undermining Ottoman power, so they could beat the Germans back home.

As it turned out, the Hashimites led the way in helping the British. They fomented the Arab Revolt. Two of Hussein’s sons, working with Lawrence, drove the Turks out of the region, clearing the way for th

e British to take Damascus and Baghdad. From there, the British could put pressure on the Ottomans.

e British to take Damascus and Baghdad. From there, the British could put pressure on the Ottomans.

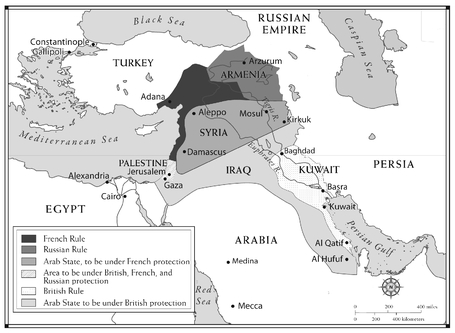

THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT

At the very time that British agents were making promises to the two Arab families, however, two European diplomats, Mark Sykes and Francois George-Picot, were meeting secretly with a map and a pencil, over a civilized cup of tea, to decide how the region should be carved up among the victorious

European

powers after the war. They agreed which part should go to Sykes’s Britain, which part to Picot’s France, and where a nod to Russian interests might be appropriate. Which part the Arabs should get went curiously unmentioned.

European

powers after the war. They agreed which part should go to Sykes’s Britain, which part to Picot’s France, and where a nod to Russian interests might be appropriate. Which part the Arabs should get went curiously unmentioned.

All these ingredients portended trouble enough, but wait, as they say on late-night-TV infomercials, there was more! Arab nationalism was starting to bubble in Palestine and adjacent Arab-inhabited territories, including Egypt, and this had nothing to do with the dynastic aspirations of the Hashimites and Saudis. It was the secular modernists who embraced this new nationalism, all those professionals, government workers, and emerging urban bourgeoisie for whom constitutionalism and industrialism also had great appeal. In Palestine and Syria, these Arab national

ists not only demanded independence from the Ottomans and Europeans but also from the Hashimites and Saudis.

ists not only demanded independence from the Ottomans and Europeans but also from the Hashimites and Saudis.

Other books

Preparation for the Next Life by Atticus Lish

Island of the Damned by Kirsta, Alix

Deep as the Rivers (Santa Fe Trilogy) by Henke, Shirl

The Dead War Series (Book 1): Good Intentions by Simmons, D.N.

Stacey Espino by Evan's Victory

Murder by the Spoonful: An Antique Hunters Mystery by Vicki Vass

Mountain Laurel by Clayton, Donna

Lane (Made From Stone Book 1) by Saint John, T

Shades of Treason by Sandy Williams

The Sorcerer's Quest by Rain Oxford