Read Diamond in the Rough Online

Authors: Shawn Colvin

Diamond in the Rough (12 page)

In the very early days, we did some work at John’s old place on West Fourth Street, but it was later, in John’s own basement apartment on East Twelfth Street between Second and Third avenues that we started nearly every song we’ve written together. The apartment was dark and ugly, but it had some square footage, and this was important to John; he needed some space for all his instruments and recording equipment. Not only did John write, but he was an exceptional producer, even back then. Before drum machines existed, John could make a simple track swing with finger snaps and reverb, as was the case with a song called “Nothin’ on Me,” one of our first efforts and maybe the only early one that survived. It ended up on a record we made called

A Few Small Repairs.

The apartment had a couch and a chair that John had picked up from home, and we’d sit there, him with a guitar and me with my black-and-white-spotted-cover composition notebooks that I still use to this day. He was a generous, patient, encouraging co-writer, mostly because, I think, there was nothing he would rather have been doing. Most of the time I’d prefer eating glass to trying to write, but for John it was soul sustenance.

The first song John and I wrote was called “The Things She Says,” lyrics courtesy of me.

It shot like an arrow going straight to my heart,

I’d waited so long for that music to start …

Argh! It was miserable! On my part anyway. Mr. B did the song, and I had become a songwriter, of sorts. We continued, penning such classics as “Strange Feeling,” “Lucky Girl,” and “There’s No Love Like Our Love.”

Naturally, with such brilliance afoot, John and I fell in love. We’d been doing both pop and country-band gigs together and had become friends. I was really attracted to him—tall and lanky, loud and cocksure, and handsome, with dark curly hair and green eyes. Of course, when he played that guitar, the heat quotient soared. He asked me out fairly soon after meeting me, but I turned him down because I was hung up on another musician, a doe-eyed songwriter who, as it turned out, was quite the ladies’ man. This guy visited me in New York and said he’d write me from across the pond—he was going on tour in Europe—but the letters were not exactly pouring in. John tried to cut to the chase one night after a bunch of us had stayed out until dawn. It was wicked hot outside, and John had air-conditioning in his apartment, an unheard-of luxury, so he offered me a place to sleep.

I had to admit there had been instances of blatant flirtation by John that had made my heart skip a beat, like the time at a Chinese restaurant where he flatly fixed his gaze on me, reached out with his hand, scooped up some of my chow mein, and wordlessly stuffed his face with it. At the movies once, he took a piece of popcorn and stuck it up his nose, again turning to me with the driest, most sober look. Not to be outdone this time, I stuck a piece of popcorn in

my

nose, at which point he swiftly leaned over, plucked it out with his mouth, and ate it. Touché. Clearly there were sparks between us; anyone could see that. But the Roving Dreamboat was due back from Europe the very day John offered me a bed. I had to hold out for Mr. Doe Eyes.

Well, the Casanova Shakespeare arrived at my apartment basically to crash. It didn’t feel like much of a reunion, and I began to sense I’d been had, so as he slept, I went through his bag, where I found lots of letters to and from lots and lots of women. I called John and told him. He said, “Well, you were a fool.” Hanging my head in shame, I presented myself to John on a platter, and we hooked up. It was the summer of 1982. I was twenty-six years old.

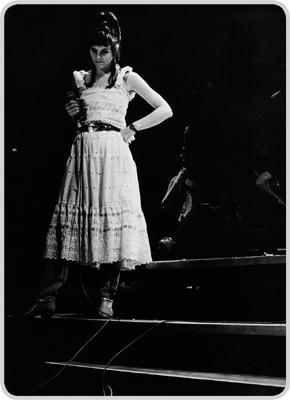

Me and John, 1982

Poor John. He fell for me at a time when I just did not know myself. I was still drinking and had no concept of being the slightest bit of an adult in a relationship. I was surviving. John had focus and confidence, enough to carry me along for a while before all my insecurity started to wear us down, but that was pretty much immediately. He took me to the movie

Brazil

the first week we were together, and I found it so disorienting that I cried through it. Much worse than that, though, was that I blamed him for it! It reminds me of something I think Roger Vadim said about being married to Brigitte Bardot—that she got mad at him in the morning for being rude to her in her dreams the night before. Perhaps I could’ve pulled this off had I been Brigitte Bardot. John was smart and funny and brilliantly creative, and he loved me and didn’t know what to do with me. Almost everything we did together was fraught with some angst from me, from the way he said good-bye on the phone to the way he held my hand to the simple fact that maybe the sky was gray one day. Things were never right; I was not right. Fairly early on in our relationship, I quit drinking, so I was on the proper path, but I had so far to go. We were together off and on for about six years and eventually fizzled out.

Regardless of whatever personal drama was unfolding between us in those days, one thing John and I could always count on was sparking each other creatively, and certainly this is part of how and why we stayed together. We got together regularly and worked on songs. I loved the music John wrote. I would hear words and melodies immediately. It was his confidence and talent and passion that kept me going. I could be furious at him for being insensitive and arrogant, and he would sit down and play “God Only Knows” and I was a goner. I should’ve seen the writing on the wall when he moved to East Twelfth Street and wouldn’t let me have anything to do with picking out his sheets. I broke up with him, and he broke up with me, and so it went until finally, at his behest, it stuck. But months after that, after making our first record and after I moved to the West Village, he came over to my new place for the first time, looked around, and began to cry. I knew why. “I grew up, didn’t I?” I said. We knew that our time had passed.

We worked literally for years on the type of pop music I mentioned before, but I knew something was missing. I was still doing gigs in folk rooms and rock clubs and country dives, and if I listed every musical genre I dabbled in for the next couple of years, we’d be here all day. Suffice it to say that the notion of becoming a rockabilly chick with a ponytail and poodle skirts thankfully blew over.

Me and Maria Muldaur as Dinettes,

Pump Boys and Dinettes,

Detroit, 1982

I even made a quick sojourn to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in 1996 and joined a band called the Red Clay Ramblers. I first became aware of them in 1985 when I saw

A Lie of the Mind,

a play by Sam Shepard, in New York. The Ramblers performed live during the play—it wasn’t a musical; this was a live sound track—and it was stunning. There was Jack Herrick, Tommy Thompson, Clay Buckner, Bland Simpson, and me. I loved being in the Ramblers. They could do anything. Our sets consisted of all manner of styles, from original stuff to Irish jigs to bluegrass to old gospel songs, complete with five singing parts. We frequented the Carolinas and played the folk festivals along the eastern seaboard and in Canada. We all starred in a musical in Cleveland called

Diamond Studs,

based on the life of Jesse James, in which I played Zee James, Jesse’s wife. Jim Lauderdale, a singer-songwriter I’d met in New York, was Jesse, and the Ramblers were his band of outlaws. (Yes, I was trying musical theater, too.) Being in the Ramblers was terrific, but it still wasn’t what I was after.

The Red Clay Ramblers, 1986

Diamond Studs, with the Red Clay Ramblers, 1986

So there came a point in my sobriety where I just threw up my hands. I was tired of trying to figure it all out, and thanks to the sober friends I’d made, I didn’t see my identity solely as a musician anymore. You go through changes when you quit using, when you quit engaging in the insanity of addiction. Eventually everything kind of comes into question. I mean, you’re making this huge choice every day not to do this thing that you were addicted to doing, and that’s a powerful experience. I was able to ask myself,

Well, what else am I able to make choices about?

I was stalling with music—I didn’t really have any other skills and didn’t know how else to make a living, but I wasn’t happy showing up to my gigs and playing anymore. I hadn’t come to any great revelation about who I was as an artist; I was still a very good copycat and not much else. It seemed pointless and empty to me, and I realized, for the first time in my life, that this doesn’t have to be it. I didn’t

have

to sing.

The friend who helped me the most was a beautiful, raven-haired, ivory-skinned, blue-blooded New Englander by the name of Kim. Kim was sober, too, had been for three years, which seemed like an eternity to me. I was extremely impressed; I wanted what she had. Kim was probably the first person, besides Stokes, who I let in after I quit drinking. Once I’d stopped, all sorts of problems cropped up, mostly to do with my phobias and panic. Much harder to manage without alcohol. When that stuff hit, I was terrified to be alone and was driven to confide in someone. In fact, I remember the very night that I decided to call Kim and talk to her. I was desperate. And I realized she knew something about me that no one else did—she understood the nature of my anxieties and how they tortured me and ruled my life, because she had the same problems. She called them her “voices.” That was such a comfort, that someone else actually had a name for what I was trying to explain. The fact that Kim called our fears “voices” makes us sound a bit schizo, but that wasn’t the nature of them. The nature of phobia and panic disorder is to intrude constantly and especially during times of pleasure, like the proverbial devil on the shoulder, but instead of enticing us to behave badly our devils told us we couldn’t have fun or be happy, that something could or would go horribly wrong if we tried. These demons lived in our heads every minute; they were our dirty secrets. With Kim not only did I unburden myself of this dark shameful secret, I reveled in knowing I was not alone, which in my opinion is the most healing thing of all. I was not alone. Maybe I wasn’t crazy. Kim presented me with this possibility, and it changed my life.

I got a job through Teddy Wainwright, Loudon’s sister, as an administrative assistant in a real-estate developer’s office and lived the life of a nine-to-fiver. I cut myself loose from all expectations. I still wrote with John and still did one solo gig a week at the Cottonwood Café, but that was all. I felt like I was family in that place. I was comfortable there. I think I got paid forty dollars a night. Oddly, it was the location of my last drink. So it doesn’t make a lot of sense, but it was a homey place for me to go.