Diamond in the Rough (14 page)

Read Diamond in the Rough Online

Authors: Shawn Colvin

When you’re out there onstage all by yourself, the audience is all you’ve got. If you want them to truly get what you’re doing up there, you need to know how to reach out to them. Nowadays it can be hard sometimes to shut me up onstage, and I like to say that the saving grace is that I’ve been in therapy so long that I just naturally wind down forty-five minutes into the set. Back then, though, I had to plan what to say. The whole thing was nerve-racking and thrilling.

Now, here’s the bottom line: Donlin wanted me back in about eight weeks’ time. And if there’s one thing I was sure of, it was that I

had

to have at least one new original song by then; my pride depended on it. I felt like I owed it to the Passim audience to grow, to have a larger catalog, to become a surer and more authentic songwriter. Of course I wanted that anyway, but, ever the procrastinator, I needed a deadline, and whenever my next gig at Passim was, that was my deadline. Pretty soon I had five songs, then seven. Bob Donlin and the audiences at Passim were invaluable to me because of that. Their expectations were higher than mine.

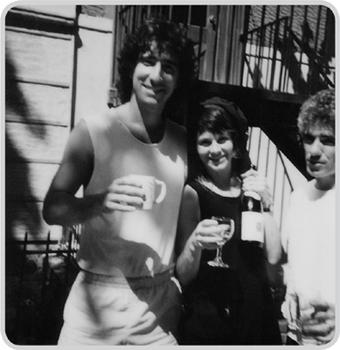

Bob and Rae Ann Donlin at Passim, Cambridge, MA, 1987

I started developing a fan base there, until I got a headlining gig and people were opening for me. All of this was before I made a record. Pretty soon I’d be playing theaters in Cambridge, not coffeehouses, and the first time I did was in September 1988, at Paine Hall on the Harvard campus, capacity 435. I put a white carnation on every seat.

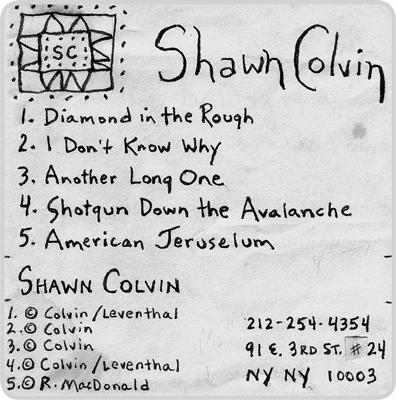

Another reason the Boston area was such fertile ground for someone like me was the presence of college radio, like stations WERS from Emerson College and WUMB from UMass Boston. I had a little cassette demo with four songs on it, and these guys played it, along with the Fast Folk recording of “I Don’t Know Why.” (Incidentally, Alison Krauss and Union Station did a cool bluegrass version of that song in 1992 on their album

Every Time You Say Goodbye.

) Those radio stations were the best marketing tool I could have had and helped immeasurably in building a following for me.

Philadelphia Folk Festival, 1988

(Photograph courtesy of John Leventhal)

Then I got a call in October 1987. Suzanne Vega had hit it big with “Luka,” and we were all atwitter. I’d actually sung on the record. I remember going into a coffee shop and hearing “Luka” playing on the radio, I could hear my little “ah” part. It lit fires under all of us; it was inspiring. It also made us jealous, which is never a bad thing. I remember going to see Jane Siberry in concert at the Bottom Line during that same period of time and walking out devastated, because I just felt like I couldn’t begin to be that cool—but those are good things, they make you try. I got a call from Suzanne’s manager saying that she was on tour, didn’t have a backup singer, and that she’d kind of like to add one. The next leg of her tour was to be all over Europe for November and December. Now, I was bound and determined not to commit to another job that would take me away from the matter at hand, which was finally doing my very own thing. But Good Lord. I’d been to Canada. That was the extent of my foreign travel. Two months in Europe, on a proper tour? I couldn’t pass it up.

I met the king of Sweden and members of Twisted Sister. I saw more cathedrals and museums than you can shake a stick at. I went running along the Seine and the Rhine, in the Alps, past Buckingham Palace, by Irish potato fields. I saw where each Beatle lived. I had an affair with a drummer who was a terrible scoundrel. We saw movies in Rome, made love to “Tunnel of Love” in Antwerp, fought in Brighton. I bought red gloves in Germany, black jeans in Switzerland, chocolate in Belgium. I listened to

Nothing Like the Sun

by Sting and

A Walk Across the Rooftops

by the Blue Nile. And I got to sing in some of the most beautiful old theaters you ever saw.

Suzanne Vega, 1987

If I had been hungry to become “someone” before Suzanne’s tour, I was starving now. I came home to New York two months later a little bruised from the road and the affair, but eons richer. Thank you, Suzanne. I felt even more under the gun to buckle down and get serious. Certainly that drive was aided by seeing what Suzanne had done. As my sister, Kay, would say, it gave me the

wantin

’

.

She says you’ve got to have the wantin’, but she also says you can’t have it too bad or it can ruin things. So I tried to stay focused and wrote another song with John, called “Steady On.”

CBS says YES, 1988—John Leventhal, me, and Steve Addabbo

(Photograph courtesy of Ron Fierstein)

Gee, it’s good to see a dream come true.

It must’ve been about June 1988. The Polaroid is of John and me and one of my managers, Steve Addabbo. We’re outside John’s studio on Twelfth Street, holding a bottle of sparkling cider. I wrote a caption on it, and it reads

“C*B*S says Y*E*S.”

As it turned out, the Suzanne Vega tour yielded a far bigger dividend than just goosing me to get on the horn with my own career. Her managers, Ron Fierstein and Steve Addabbo, took an interest in me and casually gave my four-song demo tape to Joe McEwen at Columbia Records. Joe was an A&R guy there, which meant he could sign acts, and he loved the tape. Columbia signed me, and Ron and Steve wanted to manage me. It all happened really fast.

The demo tape that got me signed

One of the first things I did was … move. At long last I left my rat- and roach-infested East Village apartment that had been home for eight years and relocated across town to a considerably nicer place in the West Village. I cried my eyes out while waiting in that empty Third Street hellhole for the cable man to come and shut down the service. I thanked that wretched place for allowing me to do the hardest growing up of my life. I’d been drunk and suicidal. I’d been sober and suicidal. I’d been through the deepest and most difficult relationship of my life, with John. I’d started therapy with Myra Friedman, whom I still talk to. I’d written the first significant song of my life, “Diamond in the Rough,” which defined everything I would write from then on. I forged friendships that would last forever. I’d had countless odd jobs and eventually landed a recording contract. I learned to be myself. So why could I not see that I would simply be bringing that self to increased square footage, a bathtub in an actual bathroom, an actual living room with a view, and no rodents? But there you have it.

Anyway, I had more important things to worry about. At thirty-two years old (Columbia suggested I list my age as thirty, and I did), I was finally going into the studio to make my own record, and even though I’d been in studios before to sing on other people’s records or demos, this just seemed ultimately like the real deal. The stakes couldn’t get any higher.

We decided to record “Diamond in the Rough” and “Shotgun Down the Avalanche” first, since, being the oldest songs, they had received the most thought and preproduction. After I’d nailed down the acoustic guitar tracks for both of them, the day came when it was time to do the vocals, and I was pretty apprehensive. We dimmed the studio lights and lit candles in the vocal booth. I probably said a prayer, or at least an affirmation: “I, Shawn Colvin, have all I need inside me not to fuck up this vocal....” We were doing “Avalanche” first. I put on headphones while John and the engineer picked a microphone for me and gave me a mix I felt good singing to. The rubber was about to meet the road. I closed my eyes and took a deep breath and laid down my first vocal take on “Shotgun” for the album we would call

Steady On.

When the song ended, I opened my eyes and waited for the verdict from the control room. I should mention that normally you sit down to do vocals and perform several attempts, then go through each take, making notes about which lines are sung best in each pass. From there you “comp” the vocal—pick out the best bits and marry them into one complete take. But I was too nervous to do a bunch of passes; I needed to know how that first one was. Was I in good form or was I self-conscious? When I walked into the control room to listen, I saw very long faces and was crestfallen. I was sure this meant I’d sucked—but no. Turns out the engineer did not press the Record button. There was nothing to listen to. I can laugh about it now, but we had to end the session for the day, and I never saw the engineer again—that’s how far it threw me. I guess somebody got rid of him. I’ve learned since to see the wisdom in not overthinking a performance, that sometimes vocally what may seem like a mistake can actually hold some emotional value, but back then I was beyond nitpicky. I would sometimes comp the vocal, not line by line, not even word by word, but syllable by

syllable.

Today I would rather chew tinfoil than go to that trouble. If you really can sing, there isn’t the need for that kind of microscopic attention, but back then, forget it. I was a total control freak about the singing.

John and I were no longer a couple. As musical partners this was our shot, but our breakup was complete by the time we were finishing

Steady On.

As you can imagine, that made for some tense studio sessions. Part of me viewed John as the enemy, because he was so bloody sure of himself and I didn’t have the maturity to experience that as anything but a power play. John knew it was “my” record, that I had to be happy, but he was also hired to be the overseer of the thing, and rightly so. These days, when we record or write together, if I think he’s acting arrogant I just threaten to slap him, but back then I threw pizza in his general direction or cried. And John? You know how men can compartmentalize and still tend to the job at hand in the midst of Armageddon? It drove me crazy.