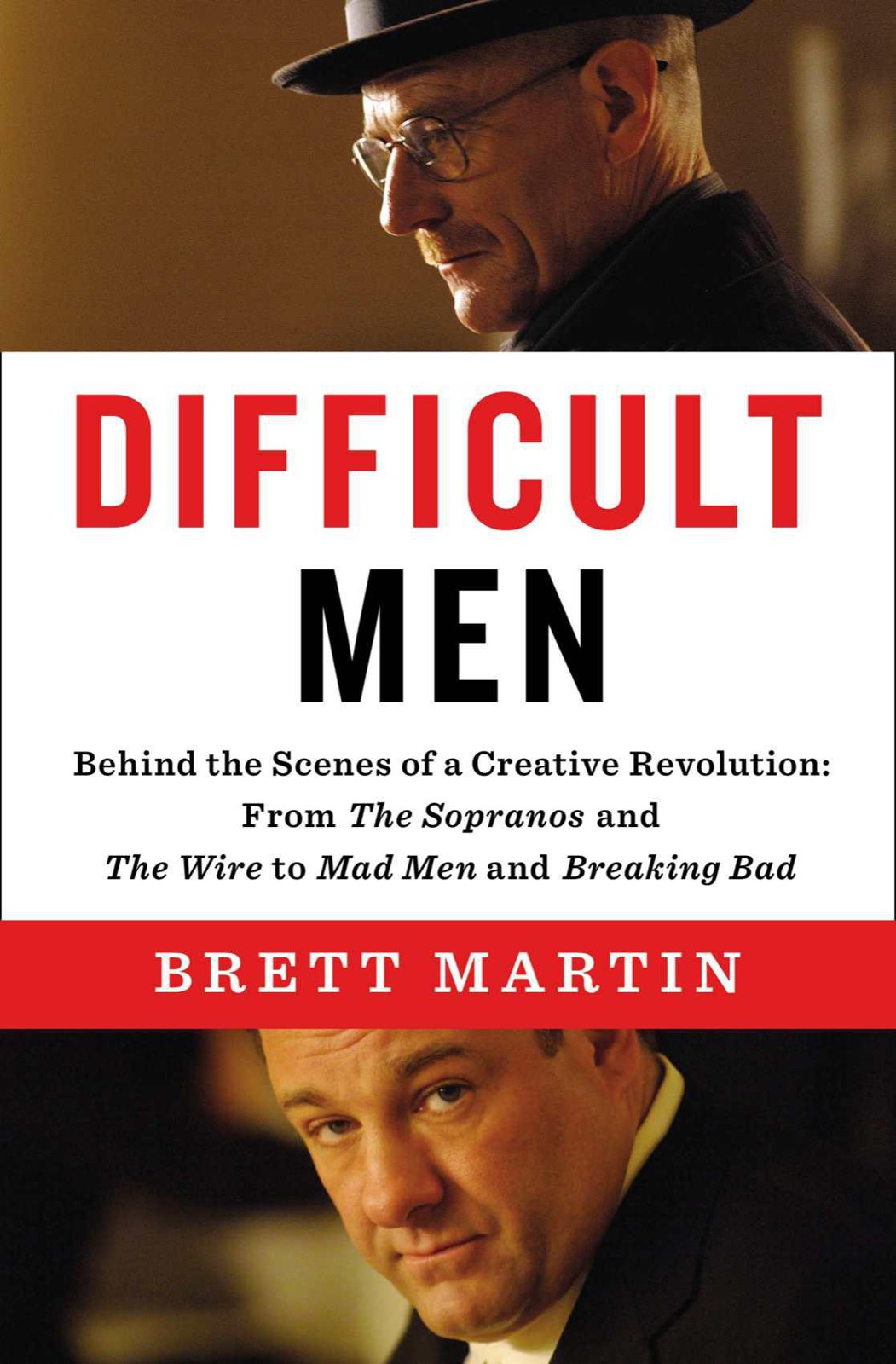

Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution: From the Sopranos and the Wire to Mad Men and Breaking Bad

Authors: Brett Martin

Tags: #Non-Fiction

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA / Canada / UK / Ireland / Australia

New Zealand / India / South Africa / China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

Copyright © Brett Martin, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint excerpts from the following copyrighted works:

“The Beast in Me” by Nick Lowe. © 1994 Planget Visions Music Limited. Used by permission of Planget Visions Music.

“I’m the Slime” words and music by Frank Zappa. © 1973 Munchkin Music. Reprinted by permission of the Zappa Family Trust. All rights reserved.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Martin, Brett, date.

Difficult men : behind the scenes of a creative revolution: from The Sopranos and The wire to Mad men and Breaking bad / Brett Martin.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-101-61779-3

1. Television series—United States. 2. Television broadcasting—Social aspects—United States. 3. Television program genres—United States. 4. Television actors and actresses—United States—Interviews. 5. Cable television—United States—History. I. Title.

PN1992.8.S4M2655 2013

791.450973'09049—dc23 2012047001

DESIGNED BY AMANDA DEWEY

TIMELINES BY MGMT DESIGN

For Barry and Barbara Martin

Four.

SHOULD WE DO THIS?

CAN

WE DO THIS?

Ten.

HAVE A TAKE. TRY NOT TO SUCK

SPOILER ALERT:

IN THE FOLLOWING PAGES, I DISCUSS A GREAT MANY PLOT POINTS OF A GREAT MANY TV SHOWS.

You think it’s easy being the boss?

TONY SOPRANO

O

ne cold winter’s evening in January 2002, Tony Soprano went missing and a small portion of the universe ground to a halt.

It did not come completely out of the blue. Ever since

The Sopranos

had debuted in 1999, turning Tony—anxiety-prone dad, New Jersey mobster, suburban seeker of meaning—into a millennial pop culture icon, the character’s frustration, volatility, and anger had often been indistinguishable from those qualities of James Gandolfini, the actor who brought them to life. The role was a punishing one, requiring not only vast amounts of nightly memorization and long days under hot lights, but also a daily descent into Tony’s psyche—at the best of times a worrisome place to dwell; at the worst, ugly, violent, and sociopathic.

Some actors—notably Edie Falco, who played Tony’s wife, Carmela Soprano—are capable of plumbing such depths without getting in over their heads. Blessed with a near photographic memory, Falco could show up for work, memorize her lines, play the most emotionally devastating of scenes, and then return happily to her trailer to join her regular companion, Marley, a gentle yellow Lab mix.

Not so Gandolfini, for whom playing Tony Soprano would always require to some extent

being

Tony Soprano. Crew members grew accustomed to hearing grunts and curses coming from his trailer as he worked up to the emotional pitch of a scene by, say, destroying a boom box radio. An intelligent and intuitive actor, Gandolfini understood this dynamic and sometimes used it to his advantage; the heavy bathrobe that became Tony’s signature, transforming him into a kind of domesticated bear, was murder under the lights in midsummer, but Gandolfini insisted on wearing it between takes. Other times, though, simulated misery became indistinguishable from the real thing—on set and off. In papers related to a divorce filing at the end of 2002, Gandolfini’s wife described increasingly serious issues with drugs and alcohol, as well as arguments during which the actor would repeatedly punch himself in the face out of frustration. To anybody who had witnessed the actor’s self-directed rage as he struggled to remember lines in front of the camera—he would berate himself in disgust, curse, smack the back of his own head—it was a plausible scenario.

It did not help that the naturally shy Gandolfini was suddenly one of the most recognizable men in America—especially in New York and New Jersey, where the show filmed and where the sight of him walking down the street with, say, a cigar was guaranteed to seed confusion in those already inclined to shout the names of fictional characters at real human beings. Unlike Falco, who could slip off Carmela’s French-tipped nails, throw on a baseball cap, and disappear in a crowd, Gandolfini—six feet tall, upward of 250 pounds—had no place to hide.

All of which had long since taken its toll by the winter of 2002. Gandolfini’s sudden refusals to work had become a semiregular occurrence. His fits were passive-aggressive: he would claim to be sick, refuse to leave his TriBeCa apartment, or simply not show up. The next day, inevitably, he would feel so wretched about his behavior and the massive logistic disruptions it had caused—akin to turning an aircraft carrier on a dime—that he would treat cast and crew to extravagant gifts. “All of a sudden there’d be a sushi chef at lunch,” one crew member remembered. “Or we’d all get massages.” It had come to be understood by all involved as part of the price of doing business, the trade-off for getting the remarkably intense, fully inhabited Tony Soprano that Gandolfini offered.

So when the actor failed to show up for a six p.m. call at Westchester County Airport to shoot the final appearance of the character Furio Giunta, a night shoot involving a helicopter, few panicked. “It was an annoyance, but it wasn’t cause for concern,” said Terence Winter, the writer-producer on set that night. “You know, ‘It’s just money.’ I mean, it was

a ton

of money—we shut down a fucking airport. Nobody was particularly sad to go home at nine thirty on a Friday night.”

Over the next twelve hours, it would become clear that this time was different. This time, Gandolfini was just

gone

.

• • •

T

he operation that came to a halt that evening was a massive one.

The Sopranos

had spread out to occupy most of two floors of Silvercup Studios, a steel-and-brick onetime bread factory at the foot of the Queensboro Bridge in Long Island City, Queens. Downstairs, the production filmed on four of Silvercup’s huge stages, including the ominously named Stage X, on which sat an endlessly reconfigurable, almost life-size model of the Soprano family’s New Jersey McMansion. The famous view of the family’s backyard—brick patio and swimming pool, practically synonymous with suburban ennui—lay rolled up on an enormous translucent polyurethane curtain that could be wheeled behind the ersatz kitchen windows and backlit when needed.

A small army, in excess of two hundred people, was employed in fabricating such details, which added up to as rich and fleshed out a universe as had ever existed on TV: carpenters, electricians, painters, seamstresses, drivers, accountants, cameramen, location scouts, caterers, writers, makeup artists, audio engineers, prop masters, set dressers, scenic designers, production assistants of every stripe. Out in Los Angeles, a whole other team of postproduction crew—editors, mixers, color correctionists, music supervisors—was stationed. Dailies were shuttled back and forth between the coasts under a fake company name—Big Box Productions—to foil spies anxious to spoil feverishly anticipated plot points. What had started three years earlier as an oddball, what-do-we-have-to-lose experiment for a network still best known for rerunning Hollywood movies had become a huge bureaucratic institution.

More than that, to be at Silvercup at that moment was to stand at the center of a television revolution. Although the change had its roots in a wave of quality network TV begun two decades before, it had started in earnest five years earlier, when the pay subscription network HBO began turning its attention to producing original, hour-long dramas. By the start of 2002, with Gandolfini at large, the medium had been transformed.

Soon the dial would begin to fill with Tony Sopranos. Within three months, a bald, stocky, flawed, but charismatic boss—this time of a band of rogue cops instead of mafiosi—would make his first appearance, on FX’s

The Shield

. Mere months after that, on

The Wire

, viewers would be introduced to a collection of Baltimore citizens that included an alcoholic, narcissistic police officer, a ruthless drug lord, and a gay, homicidal stickup boy. HBO had already followed the success of

The Sopranos

with

Six Feet Under

, a series about a family-run funeral home filled with characters that were perhaps less sociopathic than these other cable denizens but could be equally unlikable. In the wings lurked such creatures as

Deadwood

’s

Al Swearengen, as cretinous a character as would ever appear on television, much less in the role of protagonist, and

Rescue Me

’s Tommy Gavin, an alcoholic, self-destructive firefighter grappling poorly with the ghosts of 9/11. Andrew Schneider, who wrote for

The Sopranos

in its final season, had cut his teeth writing for TV’s version of

The Incredible Hulk

,

in which each episode, by rule, featured at least two instances of mild-mannered, regretful David Banner “hulking out” and morphing into a giant, senseless green id. This would turn out to be good preparation for writing a serialized cable drama twenty years later.

These were characters whom, conventional wisdom had once insisted, Americans would never allow into their living rooms: unhappy, morally compromised, complicated, deeply human. They played a seductive game with the viewer, daring them to emotionally invest in, even root for, even love, a gamut of criminals whose offenses would come to include everything from adultery and polygamy (

Mad Men

and

Big Love

)

to vampirism and serial murder (

True Blood

and

Dexter

). From the time Tony Soprano waded into his pool to welcome his flock of wayward ducks, it had been clear that viewers were willing to be seduced.

They were so, in part, because these were also men in recognizable struggle. They belonged to a species you might call Man Beset or Man Harried—badgered and bothered and thwarted by the modern world. If there was a signature prop of the era, it was the cell phone, always ringing, rarely at an opportune time and even more rarely with good news. Tony Soprano’s jaunty ring tone still provokes a visceral response in anyone who watched the show. When the period prohibited the literal use of cell phone technology, you could see it nonetheless—in the German butler trailing an old-fashioned phone after the gangster boss in

Boardwalk Empire

, or in the poor lackeys charged with delivering news to Al Swearengen, these unfortunate human proxies often bearing the consequences of the same violent wishes Tony seemed to direct to his ever-bleating phone.

Female characters, too, although most often relegated to supporting roles, were beneficiaries of the new rules of TV: suddenly allowed lives beyond merely being either obstacles or facilitators to the male hero’s progress. Instead, they were free to be venal, ruthless, misguided, and sometimes even heroic human beings in their own right—the housewife weighing her creature comforts against the crimes she knows her husband commits to provide them, in

The Sopranos

and

Breaking Bad

;

the prostitute insisting on her dignity by becoming a pimp herself, in

Deadwood

;

the secretary from Bay Ridge battling her way through the testosterone-fueled battlefield of advertising in the 1960s, in

Mad Men

.

In keeping with their protagonists, this new generation of shows would feature stories far more ambiguous and complicated than anything that television, always concerned with pleasing the widest possible audience and group of advertisers, had ever seen. They would be narratively ruthless: brooking no quarter for which might be the audience’s favorite characters, offering little in the way of catharsis or the easy resolution in which television had traditionally traded.

It would no longer be safe to assume that everything on your favorite television show would turn out all right—or even that the worst wouldn’t happen. The sudden death of regular characters, once unthinkable, became such a trope that it launched a kind of morbid parlor game, speculating on who would be next to go. I remember watching, sometime toward the end of the decade, an episode of

Dexter

—a show that took the antihero principle to an all but absurd length by featuring a serial killer as its protagonist—in which a poor victim had been strapped to a gurney, sedated, and ritually amputated limb by limb. The thing a viewer feared most, the image that could make one’s stomach crawl up his or her rib cage, was that the victim would wake up, realize his plight, and start screaming. Ten years earlier, I would have felt protected from such a sight by the rules and conventions of television; it simply would not happen, because it

could not

happen. It was a sickening, utterly thrilling sensation to realize that there was no longer any such protection.

• • •

N

ot only were these new kinds of stories, they were being told with a new kind of formal structure. That cable shows had shorter seasons than those on traditional network television—twelve or thirteen episodes compared with twenty-two—was only the beginning, though by no means unimportant. Thirteen episodes meant more time and care devoted to the writing of each. It meant tighter, more focused serial stories. It meant less financial risk on the part of the network, which translated to more creative risk on-screen.

The result was a storytelling architecture you could picture as a colonnade—each episode a brick with its own solid, satisfying shape, but also part of a season-long arc that, in turn, would stand linked to other seasons to form a coherent, freestanding work of art. (The traditional networks, meanwhile, were rediscovering their love of the exact opposite—procedural franchises such as

CSI

and

Law & Order,

which featured stand-alone episodes that could be easily rearranged and sold into syndication.) The new structure allowed huge creative freedom: to develop characters over long stretches of time, to tell stories over the course of fifty hours or more, the equivalent of countless movies.

Indeed, TV has always been reflexively compared with film, but this form of ongoing, open-ended storytelling was, as an oft-used comparison had it, closer to another explosion of high art in a vulgar pop medium: the Victorian serialized novel. That revolution also had been facilitated by upheavals in how stories were created, produced, distributed, and consumed: higher literacy, cheaper printing methods, the rise of a consumer class. Like the new TV, the best of the serials—by Dickens, Trollope, George Eliot—created suspense through expansive characterization rather than mere cliff-hangers. And like it, too, the new literary form invested in the writer both enormous power (since he or she alone could deliver the coal to keep the narrative train running) and enormous pressure: “In writing, or rather publishing periodically, the author has no time to be idle; he must always be lively, pathetic, amusing, or instructive; his pen must never flag—his imagination never tire,” wrote one contemporary critic in the London

Morning Herald.

Or as Dickens put it, in journals and letters to friends: “I MUST write!”

The result, according to one scholar writing of Dickens’s

The Pickwick Papers

,

the first hugely successful serial, certainly sounds familiar: “At a single stroke . . . something permanent and novel-like was created out of something ephemeral and episodic.” Moreover, like the Victorian serialists, the creators of this new television found that the inherent features of their form—a vast canvas, intertwining story lines, twists and turns and backtracks in characters’ progress—happened to be singularly equipped not only to fulfill commercial demands, but also to address the big issues of a decadent empire: violence, sexuality, addiction, family, class. These issues became the defining tropes of cable drama. And just like the Victorian writers, TV’s auteurs embraced the irony of critiquing a society overwhelmed by industrial consumerism by using precisely that society’s most industrialized, consumerist media invention. In many ways, this was TV

about

what TV had wrought.