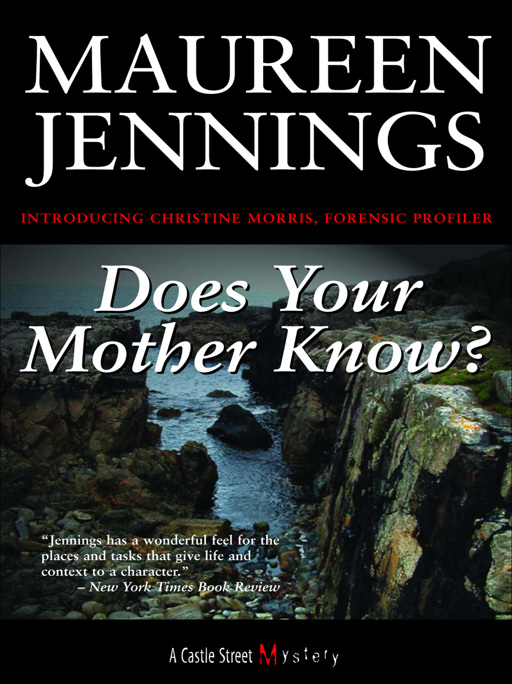

Does Your Mother Know?

DOES YOUR

MOTHER

KNOW?

DOES YOUR

MOTHER

KNOW?

Maureen Jennings

A Castle Street Mystery

Copyright © Maureen Jennings, 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Editor: Barry Jowett

Copy-editor: Patricia Kennedy

Design: Jennifer Scott

Printer: Friesens

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Jennings, Maureen

Does your mother know? / Maureen Jennings.

ISBN-10: 1-55002-639-9

ISBN-13: 978-1-55002-639-9

I. Title.

PS8569.E562D63 2006 C813’.54 C2006-903855-4

2 3 4 5 10 09 08 07

We acknowledge the support of the

Canada Council for the Arts

and the

Ontario Arts Council

for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the

Government of Canada

through the

Book Publishing Industry Development Program

and

The Association for the Export of Canadian Books

, and the

Government of Ontario

through the

Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit program

, and the

Ontario Media Development Corporation

.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

Printed and bound in Canada.

Printed on recycled paper.

Dundurn Press | Gazelle Book Services Limited | Dundurn Press |

To Iden, as always

CHAPTER ONE

The Balmoral was an elegant, old-fashioned hotel, and the conference rooms had the high ceilings and deep windows that spoke of a more generous age. I had a good view of the park below, swathes of lush green lawn and full-leaved trees bathed in the spring sunshine. I’d been in Edinburgh all week and the weather had been, as they say, “unsettled.” To tell the truth, that rather suited me. You might say I was unsettled too, and dull, cloudy days were easier to take than blue skies and everybody rushing outside to take advantage of the sun. I rather liked being shut up with the other conference attendees, with no choices to make except from the lunch menu. The police shrink had assured me this state of mind would pass soon. I knew the language: post-traumatic stress syndrome. I’d seen other cops go through it, but now it was happening to me and all I felt was weirdly numb and listless. Fortunately, the conference concerning the latest developments in the field of forensic behavioural sciences was interesting.

Just what the doctor ordered, Christine

, although it wasn’t Dr. Quealey who’d suggested it, but my new boss, Jim Henderson.

Perfect timing. Get away on our nickel and come back full of valuable information, which we will expect you to share.

All sessions with the shrinks were supposed to be strictly confidential, even if they were mandatory after a death, but the way he’d looked at me I was suspicious that word had got out. I was appalled at the

idea that people might be going around pitying me, so I put on my happiest face, expressed my gratitude, and packed my bags.

The sun played coy and vanished behind a cloud. I shifted in the stiff-backed, Regency-style chair and tried to concentrate. My attention was impaired not only by the lack of oxygen and too many deep-fried scampi at lunch, but also by the absence of any sound system. The presenter was a petite woman with a matching voice. She also had a Scottish accent, which meant I couldn’t understand a lot of what she said. To my ears, the native Scots sounded as if they had folded their tongues, stuck them to the top of their palates, and were chewing on them. As they also disdained to pronounce final consonants, everything melted together into one long dancing word.

“Fuss, tacka pea sov clinpepper and writ doon t’ following tittle.”

After momentary bewilderment and an exchange of glances, the group, about thirty of us, mostly male, and as far as I could tell, non-Scots, turned the pages of our notebooks and waited, pens at the ready.

The speaker, who had introduced herself as Sergeant Pamela Rowan, now said (in translation): “I’m going to give you half an hour for this next exercise. Don’t rush. It’s not a competition. Think about what you write and be as honest as you can be. Here’s the subject: What would you say has defined you? By that I mean is it your nationality? Your size? A birth defect? Your position in the family? That sort of thing. In what way has this had an impact on your life? I’m sure you see the point. In our work we want to know what fantasy our rapist is acting out. Is he too short? From a minority culture? An orphan? A single child? This last is very common as you know. All these yobbos play out some private fantasy that’s consistent from crime to crime. He makes his victims lie face-down; wear granny knickers; say naughty words; swallow his semen; and so on. I realize this is probably not new to you, but I want to get across to you that, to some extent, we can work backwards as it were. The patterns can give us insight into what kind of life the yobbo had growing up.” She grinned. “No, I’m not going to ask you about your particular fantasies, so don’t worry. All I want you to do is think about your own

life in the way I just said. What has defined you? Why are you police officers, for instance? It can’t be the wages. Unless you’re from America, that is.”

Groans and hisses from some Yankee members of the group.

“For example,” she continued. “I meself was the wee gal in a family of five galumphing boys.”

There was an appreciative chuckle from the audience. She didn’t have to say more than that.

“You laughed because you’re thinking, ah, ah, she was a tomboy. True, I was for a while. But early on I realized I wasn’t going to win in that arena. All of my brothers could outrun, outshout, outpunch me, and believe me, they did all of the above. The one place we were equal was in the mind, the intellect.” She tapped herself on the side of her head. “Here, in here, I was not only as good, I was often better.” She put her hands on her hips and raised her voice. “I might not have been able to out-hit my brothers, but I could outwit the fuckers.”

The unexpected F-word dropping out of the mouth of this proper-seeming woman incited a roar of laughter. I laughed too. Not that I had brothers as such to compete with, but it was still more difficult for a woman to make headway in the Canadian police force, no matter what was said officially. I understood what Sergeant Rowan meant about the levelling effect of the intellect, and I liked that.

“Now get to work. You have half an hour. No more dillydallying.”

Somebody behind me coughed, the lung-congested cough of a heavy smoker, there was the scratch of pen on paper. I glanced around. I wasn’t the only one dilly-dallying. More than one pair of eyes were focussed out the window. With few exceptions, the men, all of them in the field of crime prevention, had what I’d come to think of as a typical “cop” look. A mask of politeness covered any errant emotions, but couldn’t quite hide the perpetual wariness behind the eyes of everybody I’d ever known on the police force. I wore the mask too.

I brought myself back to the assigned task. It was edging a bit too close to the personal for my liking, and I was procrastinating. I

wondered idly what the guy in front of me was writing so earnestly. He was big, with wide shoulders and hips, and he was spilling over the sides of the chair. I think his name was Phil or Pete. A fellow Canuck, I knew that much. A boy who grows up quickly is often picked on, unless he discovers he can intimidate if he needs to. Had Phil/Pete always been forced to prove himself? As for me, I was slightly above average height, at the moment slightly below normal weight, attractive enough not to obsess about it, not so pretty that it became a crutch. How’s that for non-revealing information?

The earnestness in the room was infectious. All right, what

did

define me? First thing, of course, unquestionably, was being the only child of a single mother. No, to be more precise, being the daughter of Joan Morris, itinerant hairdresser, part-time short-order cook, occasional whore.

Whoa. That came out with a little spurt of acid. Joan would never acknowledge the whore part, of course. But in my book, an endless parade of boyfriends, many unnamed, who stayed for a night or two, then departed, occasionally leaving money or booze on the kitchen table, qualified her for the label.

I stopped writing. I had thought I was long over being angry. And I was — most of the time. But if you wanted something that defined me, that was it. The impact that situation had had on my life made far too long a story to write in half an hour, but I know it influenced my choice of a career. If your childhood is in perpetual chaos, you can grow up craving order and believing in it. And according to Dr. Q., my past had affected my judgement in the case of Ms. Sondra DeLuca.

It’s only human, you were tired, overworked, and you identified with the child.

I didn’t buy that. Anybody with any sensation in their body would have reacted when they saw Sunrise, which was the ridiculous name her mother had saddled her with. My childhood had been one long tea in the royal nursery in comparison to that little being’s.

My best friend is Paula Jackson, and her dad is an ex-cop. Old school.

Sure you meet the scum of the earth in this job. Ignorant at best. At worst, plain evil. But it isn’t your job to judge them. It’s your job to enforce the law, end of story.

I glanced up and met the eyes of Sergeant Rowan, who smiled at me reassuringly. I must have been scowling. I reassured her back and returned to the exercise. Then, the door at the front of the room opened and a disembodied hand beckoned. Pamela walked over; there was a brief whispered conversation. She accepted a piece of paper and returned to the centre of the room.

“Sorry to interrupt, but can I have your attention for a moment.... Would Detective Sergeant Christine Morris please identify herself?”

A jolt of adrenaline shot through my body, a long-conditioned response to such public inquiries.

I raised my hand. “Yes? ”

Ms. Rowan came toward me. “A message for you.”

I unfolded the paper she handed me. “

Urgent. Please telephone Inspector Harris, Northern Constabulary

.”

Ms. Rowan was waiting, sympathy and curiosity in her eyes.

“Do you know what it’s about?” I asked.

“They didna say, except to ask if you would ring as soon as possible. Come back later and I’ll give you the handouts.”

I nodded thanks, gathered up my things — briefcase, jacket, purse — and eased myself along the row of chairs.

I couldn’t stop my pulse from beating faster. An urgent call could mean anything, of course — more fallout from the DeLuca situation, for instance — but I realized my thoughts had zipped straight back to my mother. That track was the oldest and deepest. I expected this message would concern Joan. They always did. What was that question again? What was the thing that defined me and what impact had it had on my life?

CHAPTER TWO

I decided to follow up on the call from the privacy of my room and as I left, I could sense the curious eyes following me. And how familiar was that?

“

Will Christine Morris please come to the office immediately?

” Occasionally this meant my mother wanted me to call her because she’d got locked out, the most frequent reason, or she needed some cash, or she was going on a short trip with her latest boyfriend and could I go stay with Paula, etc. These calls were always of the utmost urgency. Sometimes she showed up at school. She was usually rude, on her way to being drunk, or briefly recovering from being drunk. During my university years the phone calls were less frequent, probably because I’d travelled to the other side of the country, but after I graduated and joined the Toronto police force, she seemed to think she now had an extended family, and I received calls on a regular basis from various police departments.

Did I know my mother was homeless? Drunk and disorderly? Looking for me?

When the latest in the succession of boyfriends absorbed her, I’d have a reprieve until the inevitable happened and she was dumped. Then there would be a deluge of calls, to her “only child and blood.” This meant she needed money. And I always sent it, in spite of excellent advice to the contrary from well-meaning friends.