Dog Sense (32 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

After decades of neglecting the topic, scientists have recently begun to probe the ways dogs “think.” Biologists and psychologists interested in canine intelligence, are now examining the more complex things that dogs' brains can doâand, indeed, what they apparently can't do. What's becoming clear is how domestication may have affected their

intelligence, and also why it seems to mesh so well with our own. Recently, primatologists have come to realize that domestic dogs can outperform even chimpanzees in some very specific ways (although there seems little doubt that chimps are more “intelligent” overall, however that is defined). Some researchers in this field

3

have even proposed that dogs have a special brand of intelligence, unique in the animal kingdom, that they “coevolved” with us humans as part of the process of domestication.

Other scientists make direct comparisons between the cognitive abilities of dogs and those of human children, but these are not necessarily helpful. For example, in one study, dogs' “word-learning” ability was claimed to be comparable to that of a two-year-old; their ability to understand goal-directed behavior, to that of an infant between three and twelve months old; and so on. Such attempts to anchor the dog's abilities to a particular stage of human development may be illuminating in some respects but, inasmuch as they are entirely anthropocentric, must also underestimate the dog's capacity to just be a dog. How, for example, can one use this approach to quantify the dog's ability to detect bombs by their odor aloneâsomething an adult human, let alone a child, could

never

do unaided? In any case, it is not clear to me what this approach tells us about how dogs perceive people; it seems unlikely that this aspect of canine intelligence could ever be encapsulated in a simple statement like “Dogs think of their owners the way a three-year-old child thinks of his parents.” Dogs are much more complex than such a statement implies, and, as noted earlier, their intelligence is unique, shaped by evolution (when they were wolves) as well as by domestication. Moreover, it seems but a short step from comparing their intelligence with that of children to regarding them

as

children, albeit four-legged ones, and treating them as “little people” rather than as the dogs they actually are.

Analyzing canine intelligence is not straightforward. Just as we can never be sure precisely what the inner world of canine emotion is really like, we will probably never be certain whether dogs think the same way that we do. Science has so far been unable to tell us how self-aware dogs are, much less whether they have anything like our conscious thoughts. This is not surprising, since neither scientists nor philosophers

can agree about what the consciousness of humans consists of, let alone that of animals. However, it is possible to examine scientifically whether dogs can or cannot

do

various things and then to infer the kinds of thoughts they might have, bearing in mind that, as dogs, they may not have the same priorities that we (or other animals) have in the same situation.

I have a good reason for delving into dogs' actual intellectual capabilities rather than assuming, as many owners and even some scientists seem to, that their abilities are simply marginally inferior to ours. If we overestimate their ability to reason, then we are led into the trap of making them accountable for their actions in situations where they are actually unaware of what they are doing. If a dog could really work out what his owner was thinking when she arrived home to find her shoe in tatters, then punishment for that “crime” would work: The dog would be able to reason that he was being punished for something he had done a while ago rather than for whatever he happened to be doing at the moment the key turned in the door. As soon as we start treating dogs like “little people” rather than like the dogs they are, our actions become incomprehensible or misleading. Indeed, our actions are of such importance to dogs (as confirmed by virtually every piece of research done on their cognitive abilities), they inevitably become confused and distressed when unable to understand us.

The simpler forms of learning both enable dogs to piece the world together and allow us to train them to behave the way we want them to. But dogs can also think for themselves: They don't just have

feelings

about the world but also, in their own way, have

knowledge

about their physical environment and the other animals around them (including humans, of course).

The formal study of canine intelligence dates back to the early-twentieth-century work of Edward Thorndike. Thorndike's approach to studying how animals learn was different from Pavlov's; he was more interested in how they solve problems. Many of his experiments involved placing animals, usually domestic dogs or young cats, into

puzzle-boxes

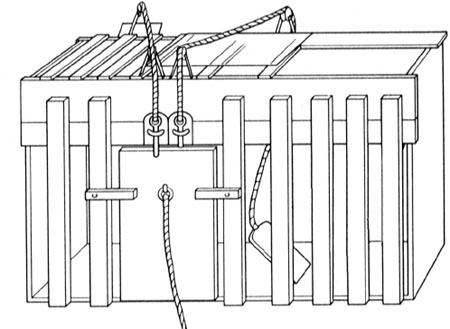

of his own devising. These could be opened from the inside when the animal performed some kind of action. As you can see in the puzzle-box

illustration, the door was attached to a weight that would pull it out of the way once the dog had unlatched it. The latch could be one of the wooden toggles on either side of the door, which the dog could paw upright by pushing its foot through the gap between the slats. Or it could be a bolt at the top of the door, connected by a loop of rope hanging from the roof that the dog could pull on with its teeth. Or it could be a treadle in the middle of the floor, which the dog had to press with its paw in order to release the door.

Thorndike's puzzle-box

Thorndike was interested in finding out how the dogs solved the problem of getting out of the box and also whether they subsequently remembered how they'd done it. At the time, many people believed that animals like cats and dogs were capable of considerable insightâthat they could, as it were, sit down and think things out. Thorndike, however, believed that a much simpler explanation would suffice.

Thorndike considered the possibility that simple associative learning, coupled with the dog's natural inquisitiveness, might actually explain such apparently intelligent behavior. He found that his dogs would initially scrabble around the puzzle-box until they blundered on the mechanism that would let them out. He then fed them, as a reward, and put them straight back into the box to see if they could now escape any faster. If the dogs had insight into what they'd done, they would have immediately returned to the lever or pedal that had previously let

them out. But in fact the dogs rarely did this. However, after repeated sessions in the box, they took less and less time to escape and eventually did start going immediately to the releasing mechanism.

Largely on the basis of these experiments, Thorndike came up with the concept of

trial-and-error

learning. Animals faced with a problem to solve will try out a variety of tactics that they would normally use in such a situation (in this case, being trapped). When one of these tactics happens to work, it produces rewards (in this case, being let out and then fed). The next time they are in a similar situation they will be more likely to perform the action that got them out last time or more likely to focus on the area where they had been when the door had opened on previous occasions. Both are explainable by simple operant conditioning: Either repeat whatever action preceded the previous escape or go to the place where you were immediately before the door opened (or both). This behavior requires no insightâno problem-solving skillsâon the part of the dog. Based on Thorndike's experiments and others like them, scientists now believe that dogs have rather limited powers of reasoning, certainly inferior to those of chimpanzees (and even a few birds).

The point here is not that dogs are stupid but, rather, that their brand of intelligence differs from the primate model. Though Thorndike's dogs showed little evidence of problem-solving skills, they did an excellent job of recalling the correct escape method. In fact, they retained this memory for several months, even without any further exposure to the puzzle-box. (Dogs' retention of skills they have acquired is generally very good, but they find it much harder to remember for more than a few seconds things they have merely

observed

.)

Memories of events, as opposed to memories of their own actions, may not be of great value to canidsâindeed, they may be confusing. Canids, especially foxes, are known to be capable of remembering where they buried food, for days or even weeks afterward. Since the ability to retrieve food in this way is clearly adaptive, it is believed that they evolved the ability to recall where they buried the food. Conversely, canids are often faced with the problem of what to do when the prey they are chasing disappears. This is not something that is useful for them to remember for very long, because prey is unlikely to remain in one place for more than a short time without leaving some other clue. If the

prey isn't where it vanished and its scent is fading fast, then it's probably long goneâand better to move on to another hunting site than to hang around hoping that it's stupid enough to return to the very place it had just been chased away from. Thus evolution seems not to have selected for retention of such information for more than a few seconds.

Dogs' short-term memory has been investigated experimentally. Using a method called

visual displacement

, scientists have tested how long dogs can remember where something has disappeared.

4

Initially each dog is taught that its favorite toy is hidden behind one of four identical boxes: It first watches the experimenter hiding the toy and is then allowed to retrieve it. Once it reliably goes to just the box it has seen the toy disappear behind and is no longer searching the boxes at random, the dog can be tested to see how long it remembers where the toy has been hidden. In this second phase of the experiment, a screen is placed between the dog and the boxes immediately after the toy has been hidden, so that the dog has to remember which box its toy is behind. Then when the screen is removed, it has to recall that memory in order to locate the correct box. If it can't, then it will go back to searching the boxes at random. If the screen is kept in place for only a few seconds, most dogs will go straight to the correct box, showing that they are indeed capable of both memorizing and recalling the location, provided the interruption is only brief. However, just a thirty-second delay is enough to induce mistakes. (Although dogs make even more mistakes after a minute's delay, they do not get significantly worse if the screen is left in place for four minutes, at which point many are still performing better than chance.) Subsequent experiments have shown that dogs are better at remembering where things have disappeared in relation to their own positions (“to my left”) than in relation to landmarks (“under the box that has boxes on either side”). Overall, many dogs' short-term memories of single items appear to be rather fallible, perhaps because they are much more interested in working out what people want them to do in the here-and-now than in recalling precisely what happened a few minutes ago. This is not to say, however, that they pay no attention to the more fixed features of their surroundings; if that were the case, they (or their evolutionary forebears) would quickly get lost.

Although most pet dogs don't

have

to memorize the features of the environment where they live (because most of the time we humans decide where they can go and where they can't), they nevertheless retain their wild ancestors' ability to find their way around and can use it if they need to. Indeed, dogs have very good memories for placesâas might be expected from the descendants of animals that roamed widely in search of food. They have a variety of cognitive methods at their disposal for this purpose, such as the ability to memorize landmarks, but also more complex skills such as constructing mental maps of how those landmarks are distributed. Landmark-learning doesn't require a complex brainâit's how many insects find their way aroundâbut it is useful nonetheless and, indeed, an essential part of more complex skills. Just as humans do, dogs effortlessly and continuously memorize the features of their surroundings; unlike us, however, they rely heavily on what things smell like. We might recall turning left around a dark green shrub; a dog would remember that shrub as smelling of orange with grassy top-notes. Yet despite these differences, dogs continually store (and then, presumably, gradually forget) information about features of the environment that they've recently encountered.

The dog's propensity for memorizing landmarks can actually impede training. Younger dogs are so good at learning locations that they often spontaneously memorize their surroundings as part of the set of cues that tells them to do something. For example, puppies taught the verbal command “sit” in a training class may forget it as soon as they get homeâbecause, in addition to the command, they have spontaneously memorized some feature of the room where the class was held as the relevant cue and, when in different surroundings, don't recognize the command.