Don Tarquinio: A Kataleptic Phantasmatic Romance (Valancourt eClassics) (10 page)

Read Don Tarquinio: A Kataleptic Phantasmatic Romance (Valancourt eClassics) Online

Authors: Frederick Rolfe,Fr. Rolfe,Baron Corvo

XVIII

All the women in the audience-chamber were plebeian, ugly, stinking. But this most beautiful princess brought in the odours of a garden of fragrant herbs; and, among the bevy attending her, I saw my maid.

Her eyelashes were lowered: but, every now and then, she flashed a glance on this side and on that, as though she were seeking something. I knew what she was seeking.

But I shrank down in my corner, pulling the impetuous Gioffredo with me: for I was not conscious that the opportune moment had arrived, even now.

The crowd opened a pathway for the tyrant. A stool was set for her under the canopy near Ippolito. Her maids-of-honour stood behind her. All their hair was dyed yellow with oil of honey in imitation of their mistress: but my maid’s hair was as black as a sapphire in a night without light.

The chamberlains emptied a great space in front of the dais, pressing back the crowd.

But I and Gioffredo thrust ourselves through, not to the front rank but to the second: for I did not wish to be seen, and I did wish to hear.

The tyrant thus addressed the cardinal, saying:

“We are come, o lord cardinal, from visiting Our mother. Madonna Giovannozza

[1]

rejoiceth by cause that the Keltic soldiers are departed: for she hath been in terror lest they should rob the blossoms of her orchard, the which is her heart’s treasure; and the revenues of her late husband’s bequest suffice not for the pay of an armed guard. Wherefore, We are sworn to ask Our Most Blessed Father for the immunity of her inn

[2]

against taxation and against the excise-duty on wines, so that she may reap a little profit in these hard times.”

She spoke rapidly, as her young brother did, but in a voice which was very sweet and soft to hear. But it was clear to me that she had other more important things to say by side of this gossip. Ippolito also perceived it: for he sagaciously nodded his head, smiling in silence.

The tyrant continued, saying:

“Thou goest at noon to dine with Our Most Blessed Father, o Cardinal of Ferrara. His Blessedness is very lonely, very grave. He taketh hardly the defect of the Vicechancellor, whom He hath loved much: for He cannot see that Sforza needs must stand by Sforza in these horrid quarrels. As for those Keltic invaders, He saith that the end is not yet: that, though they go now, anon they will return: that there will be war, perhaps during

iij

months, but not in the City: but that there first will be happenings which will astound the Christian King.”

Ippolito appended grave nods and impenetrable smiles.

Madonna Lucrezia again tried to approach the matter which she had in mind, saying:

“After Lent, o lord cardinal, it is Our intention to dine daily in the gardens of La Magliana

[3]

to the sound of luths. Madonna Giulia

[4]

hath brought

iiij

luthists from Venice; and one is an improvisatore. We therefore beg that thou wilt be Our beadsman, giving Us the benefit of thine holy prayers for fair weather after Eastertide.”

Ippolito conceded a gesture of assent. What was the use of a cardinal-deacon, excepting to pray for fair weather for fair ladies who were minded to dine in gardens, his aspect seemed to say. Having obtained so small a boon, the tyrant (womanlike) instantly demanded a great one, saying:

“And now, o Cardinal of Ferrara, We desire to hear thy news.”

To whom he responded, saying:

“Since yesterday, divers strange things have happened. One of Our athletes, by race a Dacian, hath been murdered; and his murderer even now is tolerating torment before strangulation.”

Madonna Lucrezia interrupted, saying:

“The news which We desire are not of that nasty species.”

Ippolito added:

“There are not any news of affairs known to Us, save those of Our family and those which Thine Exalted Tranquillity hath named.”

Madonna Lucrezia looked him up and down. She would try the effect of a taunt; and continued, saying:

“Our Most Blessed Father sitteth in the Castle of Santangelo, dumb, but smiling at His thoughts. Of what pleasant thing is He thinking? There is not anyone in the City who will respond to Our inquiries. The others, perchance, cannot: but thou canst and wilt not, o Cardinal of Ferrara.”

She was becoming indignant, but sorry. A dark woman never ought to inflame herself with anger, by cause that the black or the brown of her hair and the red of her rage are the colours of our old enemy, the devil: but fury augmenteth the beauty of a fair woman to the highest degree, for it brighteneth the clear blue of her eyes, while the poppy-colour of her face is exquisitely allied with the straw-colour of her hair. At such a moment, she resembleth a joyful field ready for reaping; and happy is the youth who is bold enough to reap.

Ippolito was a little confused; but he used himself serenely enough, saying that (for his part) he was willing but unable.

The tyrant no longer restrained her spleen. She spoke, while her fair cheeks flamed, scornfully saying:

“It is well known to Us that the Cardinal of Ferrara doth profess himself to be the friend of the Cardinal of Valencia. Our mind telleth Us also that the said Cesare is this day in some dire peril, having gone away with that very abominable Keltic king. Wherefore We should have thought that the Cardinal of Ferrara, having so many vigorous familiars in his hand, would be doing something for the safety of his friend. Or are all these mighty and magnificent gentlemen merely for show but not for use?”

And then, o Prospero, my darling little maid burst out incontinent, saying:

“At least one of the Lord Cardinal’s gentlemen is useful and willing as well as magnificent and mighty and very beautiful, o Exalted Tranquillity.”

Everybody shouted with laughter at such effrontery. Her blushes burned her like a fire: but she maintained her situation bravely in front of the other girls; and her eyes glittered like stars, blue-black, brilliantly beaming. I almost believed that she actually saw me: but I kept my face behind the head of a fool, peeping between his hood and the twisted liripipe of the same.

Madonna Lucrezia changed her posture, with the alacrity of one who findeth that her seat is a nest of scorpions, demanding shrilly, mockingly:

“What doth a maid-of-honour know about a cardinal’s beautiful gentlemen?”

There was a noise at the door; and chamberlains entered announcing:

“The Exalted Potency of the Princess Sancia d’Aragon Borgia of Squillace.”

I instantly cuddled Gioffredo’s head as tightly as possible, pressing one wrist into his very wide-open mouth; and, at the same time, despite my fast failing strength, with the other hand I seized him in a certain grip from which no one may move an hair’s breadth. Nor did I release him without a promise of silence, asked in a whisper, granted by green eyes bulging and glaring. Thus we

ij

stood staring at the form of his wife.

[1]

This was her nickname (Big Jenny), which she commonly bore in accordance with the Roman custom: but her real name was Giovanna de’ Catanei.

[2]

The Lion Inn in Bear Street, a bequest from her deceased husband. Excepting perhaps the sixty Roman patricians, no one in those days thought a whit the worse of a lady for getting her living banaysically than people do now. Madonna de’ Catanei was neither a barmaid nor a female boniface. She was the proprietor of the most celebrated hostelry in Rome; and lived privately on her income in a villa near San Pietro ad Vincula.

[3]

A paparchal villa in the Campagna, ten miles S.E. of Rome, founded by Xystus the Fourth and enlarged by Innocent the Eighth, the predecessor of Alexander the Sixth.

[4]

Giulia (Farnese) Orsini, a lady of the court.

XVIIII

She came in with her own galaxy of maids-of-honour, all in black habits, waving her hands and swaying her head distractedly, querulously blaming everybody.

She was a fat girl, very long in the back, red-haired, white-fleshed; and her eyes resembled those of a bereaved cow. A large nurse stepped closely behind her, carrying a baby swaddled on a board, terribly squealing. This, together with the recriminations now proceeding at the throne, and the occasional howls of the Princess of Squillace, and the shrieking laughter of the crowd, produced a tumult resembling that of Navona at Epiphany.

[1]

Another stool having been set on the dais, the new comers arranged themselves in order.

Gioffredo’s wife wept loudly until everyone was silent. Then she began to speak, saying:

“Ah-hoo, o Lord Cardinal, We are come for consolation, ah-hoo, ah-hoo, ah-he-he-he-he. For thou shalt know that Cesare hath gone to Naples; and Our Fredo hath followed him, ah-hoo, ah-hoo, ah-he-he-he-he. We desire to know why. Ah-hoo. We desire to know why. Ah-he-he-he-he-hoo. Now we all will be compelled to sell our jewels. Now we all will be compelled to be ransomed, ah-hoo, ah-hoo. Why hath not Lucrezia prevented Cesare from going? Why hath not this Purpled Person prevented Our Fredo from following? Both those impetuous adolescents were in this very palace during the past night: for Fredo himself said so. And now he hath deserted Us, his most loving wife; and hath ridden after Cesare with a mere handful of an escort, and on swift horses, ah-hoo. Three hours ago, We missed him. Four hours and who knoweth how much more, have We been a widow, and Our baby but a month old, a-hoo, a-hoo. Lord Cardinal, We desire Our husband. Ah-he-he-he-he-hoo. Hoo.”

She tottered toward the large nurse; and set herself to moo over her baby, mumbling it with her lips from time to time. I wished for the death of the brat and its mother: for I feared that I should not be able to restrain Gioffredo much longer. That prince was wriggling like a clean dolphin.

Ippolito’s visage showed the extreme discomfort of his mind.

The Tyrant Lucrezia spat out a sentence, saying:

“We are unable to treat such people with patience. Women do not become widows every time when their husbands run after the soldiers. Hath not Our Own husband gone to assist his cousin, Duke Lodovico Sforza-Visconti of Milan, and the Kelts,

[2]

some months ago, before these wars began? And is there any Roman temerarious enough, or suburban enough, to denominate Alexander’s daughter Widow on that count?”

The Princess Sancia bewailed herself, saying that she wanted her Fredo.

But now indeed Gioffredo began to jump about, disturbing the people whose bodies had concealed us; and I was totally unable to hold him. For, having broken away from me, he bounded towards his wife, very agitated, roaring like Stentor. And, at the same moment, Ippolito, catching a glimpse of me, emitted tremendous shouts of welcome, calling me by name.

But mine eyes were directed toward my maid. Now that this long (and, as I think, rather silly) period of concealment at length was concluded, I had no thoughts in my breast save of her who, unknowingly, had nerved me to my great exploit. Wherefore, there being no longer any cause for secrecy, I attempted to rush to her.

But it became clear that I could do no more than limp, slowly, painfully, very ungracefully; and, when

vij

paces had extricated me from the crowd, placing me alone in the empty space in the middle of the audience-chamber, where I instantly felt myself to be the target for the arrows of more than

dccc

eyes, then I suddenly remembered that my yellow-silver hair was knotted in an abominable night-cap, that the flesh of my body and limbs was a great deal more than half-naked, that I stank most indelicately, that I was besmirched and begrimed from head to foot with sweat and mire and every kind of uncleanness.

Such a terrific piece of knowledge caused me to utter yells, and to bolt (like a rabbit into his burrow) through the tapestried door at the side of the audience-chamber. Tumults of laughter pursued me; and lent wings to my flight.

XX

Having made shift to get as far as the threshold of my proper antechamber, my limbs failed me there; and I sank to the ground.

The way through the palace was long and devious. All the family was in the audience-chamber; and I encountered no assistant on my painful passage.

I was so utterly exhausted that I ceased to care for anything at all; and the mind in my breast advised me to lie still, until such time when my servitors should come to me. For, it being known that I had returned to the palace, I did not doubt but that search would be made for me.

That antechamber, o Prospero, was a very long room panelled with slabs of lapis-lazuli and malachite. The ceiling of it was painted with the images of the Divine Hylas struggling with the nymphs.

I

deliberated that my maid was fairer than any of these; and I wondered what she might be doing at that moment.

The sunlight streamed in through the row of windows which abutted on the court, brightening the gilding of the cornice. On the other side all the outer doors of my divers chambers stood open; but I continued to lie where I was on the very threshold of the antechamber, happy, drowsy, not anxious to go further.

Anon, a posse of my familiars came running up the stairs behind me, moaning and shouting commiseration for my condition: who, having carried me into the bathing-chamber, stripped me, and began to perform their office. And now indeed my mind devised new schemes; and I became most anxious for instant restoration of my normal aspect. Wherefore, I condemned them for a parcel of fools and lazy oaves; and I issued divers peremptory commandments.

Pages galloped hither and thither to and from the wardrobe, bringing towels, ewers of various waters, and all the apparatus of washing, with numerous ceremonial garments, trays of jewels, flasks of the quintessence of southernwood, and the paraphernalia of mine estate.

While my flesh was being scrubbed, I selected a certain very singular new habit, which, by the benignance of my stars, I had caused to be made, when I first entered the City, for just such an occasion as the present appeared likely to be. For now my mind was persuaded that but one more turn of Divine Fortune’s wheel would bring me to the top. But here my meditations were interrupted.

Ippolito with the Tyrant Lucrezia, and Gioffredo with the Princess Sancia, and mine own maid with all the company, came bounding up the stair inquiring for me.

A gesture from the chamberlains at my door kept them in the antechamber. The said door was not quite shut; and, having put my wet hair away from mine eyes, I was able (through the crevice) to see Gioffredo and his wife going to the embrasure of one of the windows. There they sat down, billing and cooing: but the others, unseen by me, began to bombard me with questions.

Ippolito vociferated, saying:

“Gioffredo saith that thou hast done that which thou didst set out to do. Tell us of the same, o Sideynes.”

To whom I briefly responded (for, at the moment, the page on the stool was deluging me with hot water), saying:

“Pietrogorio hath received both messages; and he desireth nothing better than to die for the Cardinal of Valencia, o Hebe.”

But, when I had said this, I noted that my servitors were wearing a rather desperate aspect: nor durst they give more than deprecating gestures and sad imploring glances to my prompt interrogations. Wherefore, having commanded them to bring mirrors, I placed myself between the same in order that I might examine my person. What I saw on the flesh of my back caused me to utter certain very fervent objurgations.

The people in the antechamber with one voice instantly demanded the cause of mine anger.

To whom I indignantly responded, saying that the cyphers evidently were indelible: for vigorous scrubbing with hot water and lupin-meal only rendered my white flesh whiter, but the diagram itself remained clearly grey. It was a terrific predicament.

A certain page suggested an application of pumice: but I indignantly denied him, not being willing to have my smooth flesh roughened and ruined.

Those friends of mine in the antechamber cackled with laughter at my discomfiture; and Madonna Lucrezia implored me to exhibit the accursed inscription. Ippolito also placed a similar request: to whose voice all the others added theirs.

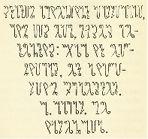

My pages having swathed me in dry sheets (covering me from head to foot like a shrouded cadaver but exposing my back), I placed myself for a few moments in the open doorway. Everybody giggled; and came near. I heard their snuffling gasps of exclamation; and felt the warm breath of the heads which stooped to gaze. No one was able to read the cyphers. These be they, o Prospero.

The Tyrant Lucrezia instantly averred that this was a lovely device for embroidering in gold on the front of a bodice, and that such a work would drive the plain Marchioness of Mantua mad with envy.

Ippolito, having traced the grey lines slowly with the tip of a loving finger (for so I felt it to be), stated an opinion that this was the kabbalistic character invented by Messer Honorios, formerly of Thebes, which Cesare was known to have taken from that erudite Gothic boy called Enrico Cornelio Agrippa von Nettesheim, who now is a councillor of the Emperor. In this case, he said, no one could read it save Cesare only and his proper familiars. As for the defilement of my flesh, he said, it no doubt would wear off in time.

And then I rejoiced very greatly: for I heard the dear little voice of my maid, saying:

“We will offer most fervent prayers that the lord cardinal’s prediction may not lack fulfilment.”

At which words Madonna Lucrezia suddenly turned to examine the last speaker, instantly becoming agog for match-making. In her opinion, so she said, so beautiful a gentleman was fit to be anybody’s husband.

Ippolito put in a salient word about the Great Ban.

That, she said, could not be permitted to run longer in despite of such an one as I had shown myself to be. For which cause, she said, the beautiful and blameless gentleman in the doorway instantly must hasten to the Castle of Santangelo with the present company, in order to tell all the tale to our Lord the Paparch Himself.

I howled with delight; and, having leaped forward into my secret chambers, I commanded the pages to indue me with mine habits using extreme celerity.

Ippolito cried out, inquiring whether Pietrogorio had read the cypher message to me, demanding also what the said noble was going to do.

To whom I responded, saying that His Nobility had read the inscription as signifying: “Statim adveniunt Gallicani, cum iis ego, obses retentus: fac ut exquiras, et auxilium praestes—The Gallicans are upon thee, with me as their hostage; find me, and lend succour:” and the autograph, “C. Car

al

de Valencia.” Also I said that I was ignorant of Pietrogorio’s plans, knowing only that he had sent me to buy up all the horses at the posthouse of Cinthyanum in Cesare’s name. And I added that the said adolescent, in my judgment, was not only a very Odysseys for deep-scheming, but also a gentleman with whom it would be safe to play odd-and-even in the dark.

Having pondered these words, Ippolito began to have an inkling of Pietrogorio’s plan. So he said. For there are but

ij

leagues between Velletri and Cinthyanum, which last city doth belong to Rome; and, if Cesare could get there and find himself master of all means of transit, he would have no difficulty in effecting a speedy return. But those

ij

leagues were the crux of the affair. Such was Ippolito’s sentence.

The Tyrant Lucrezia delivered herself of another opinion. She said that Cesare was a beast, a fine beast, an admirable beast, an irresistible beast, and just now a necessary (nay) an indispensable beast. And she was quite certain that he would contrive to cover those

ij

leagues.

But, at the moment of speaking, at length I escaped from my pages, radiant, delicate, princely, in a habit of state.