Leonardo and the Last Supper

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

Leonardo and

The Last Supper

ROSS KING

Contents

Map of Italy in 1494

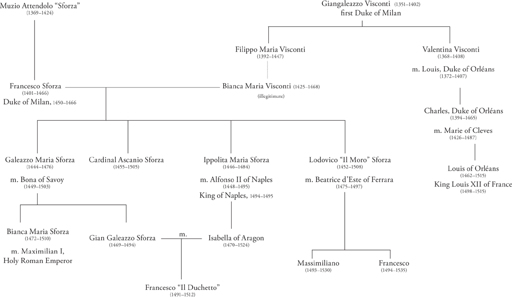

Sforza-Visconti Family Tree

The Last Supper

with Apostles Identified

CHAPTER 2: Portrait of the Artist as a Middle-Aged Man

CHAPTER 4: Dinner in Jerusalem

CHAPTER 8: “Trouble from This Side and That”

CHAPTER 9: Every Painter Paints Himself

CHAPTER 10: A Sense of Perspective

CHAPTER 11: A Sense of Proportion

CHAPTER 12: The Beloved Disciple

CHAPTER 14: The Language of the Hands

CHAPTER 15: “No One Loves the Duke”

EPILOGUE: Tell Me If I Ever Did a Thing

Color Insert

Acknowledgments

Notes

Footnotes

Selected Bibliography

Illustration Credits

A Note on the Author

Also by Ross King

For my father-in-law

Sqn. Ldr. E. H. Harris RAF (Rtd)

I wish to work miracles.

—LEONARDO DA VINCI

The Last Supper

with Apostles Identified

The astrologers and fortune-tellers were agreed: signs of the coming disasters were plain to see. In Puglia, down in the heel of Italy, three fiery suns rose into the sky. Farther north, in Tuscany, ghost riders on giant horses galloped through the air to the sound of drums and trumpets. In Florence, a Dominican friar named Girolamo Savonarola received visions of swords emerging from clouds and a black cross rising above Rome. All over Italy, statues sweated blood and women gave birth to monsters.

These strange and troubling events in the summer of 1494 foretold great changes. That year, as a chronicler later recounted, the Italian people suffered “innumerable horrible calamities.”

1

Savonarola predicted the arrival of a fierce conqueror from across the Alps who would lay waste to Italy. His dire prophecy was fulfilled soon enough. That September, King Charles VIII of France entered an Alpine pass with an army of more than thirty thousand men, bent on marching through Italy and seizing the throne of Naples. The scourge of God made an unprepossessing sight: the twenty-four-year-old

king was short, myopic, and so ill proportioned that in the words of the chronicler Francesco Guicciardini, “he seemed more like a monster than a man.”

2

His ungainly appearance and agreeable nickname, Charles the Affable, belied the fact that he was equipped with the most formidable array of weapons ever seen in Europe.

Charles VIII’s first stop was the Lombard town of Asti, where, after pawning jewels to pay his troops, he was greeted by his powerful Italian ally, Lodovico Sforza, the ruler of Milan. Savonarola may have prophesied Charles’s expedition, but it was Lodovico who had summoned him across the Alps. The forty-two-year-old Lodovico, known because of his dark complexion as Il Moro (the Moor), was as handsome, vigorous, and cunning as the French king was feeble and ugly. He had turned Milan—the duchy over which he had become the de facto ruler in 1481 after usurping his young nephew Giangaleazzo—into what the Holy Roman emperor, Maximilian, called “the most flourishing realm in Italy.”

3

But Lodovico’s head lay uneasy. The father-in-law of the feckless Giangaleazzo was Alfonso II, the new king of Naples, whose daughter Isabella deplored the usurpation and did not scruple to tell her father of her sufferings. Alfonso had an unsavory reputation. “Never was any prince more bloody, wicked, inhuman, lascivious, or gluttonous than he,” declared a French ambassador.

4

Lodovico was told to beware assassins: Neapolitans of bad repute, an adviser warned, had been dispatched to Milan “on some evil errand.”

5

Yet if Alfonso could be removed from Naples—if Charles VIII could be convinced to press his tenuous claim to its throne (his great-grandfather had been king of Naples a century earlier)—then Lodovico could rest easy in Milan. According to an observer at the French court, he had therefore begun “to tickle King Charles ... with the vanities and glories of Italy.”

6

The Duchy of Milan ran seventy miles from north to south—from the foothills of the Alps to the Po—and sixty miles from west to east. At its heart, encircled by a deep moat, crisscrossed by canals, and protected by a circuit of stone walls, lay the city of Milan itself. Lodovico’s wealth and determination had turned the city, with a population of one hundred thousand people, into Italy’s greatest. A huge fortress with cylindrical towers loomed on its northeast edge, while at the center of the city rose the walls of a new cathedral, started in 1386 but still, after a century, barely half-finished. Palaces lined the paved streets, their facades decorated with frescoes. A poet exulted that in Milan the golden age had returned, and that Lodovico’s city was full of talented artists who flocked to his court “like bees to honey.”

7

Lodovico Sforza

The poet was not merely flattering to deceive. Lodovico had been an enthusiastic patron of the arts ever since, at the age of thirteen, he commissioned a portrait of his favorite horse.

8

Under his rule, intellectual and artistic luminaries flocked to Milan: poets, painters, musicians, and architects, as well as scholars of Greek, Latin, and Hebrew. The universities in Milan and neighboring Pavia were revived. Law and medicine flourished. New buildings were commissioned; elegant cupolas bloomed on the skyline. With his own hands Lodovico laid the first stone of the beautiful church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli presso San Celso.

And yet the verdict of the chroniclers would be harsh. Italy had enjoyed forty years of relative peace. The odd skirmish still broke out, such as when Pope Sixtus IV went to war against Florence in 1478. Yet for the most part Italy’s princes vied to surpass one another not on the field of battle but in the taste and splendor of their accomplishments. Now, however, the blood-dimmed tide was loosed. By enticing Charles VIII and his thunderous weapons across the Alps, Lodovico Sforza had unwittingly unleashed—as all the stars foretold—innumerable horrible calamities.

Among the brilliant courtiers in Lodovico Sforza’s Milan was an artist celebrated above all others. “Rejoice, Milan,” wrote a poet in 1493, “that inside your walls are men with excellent honours, such as Vinci, whose skills in both drawing and painting are unrivalled by masters both ancient and modern.”

9

This virtuoso was Leonardo da Vinci who, at forty-two, was exactly the same age as Lodovico. A Tuscan who came north to Milan a dozen years earlier to seek his reputation, he must have cut a conspicuous and alluring figure at Il Moro’s court. By the accounts of his earliest biographers, he was strikingly handsome and elegant. “Outstanding physical beauty,” enthused one writer. “Beautiful in person and aspect,” observed another. “Long hair, long eyelashes, a very long beard, and a true nobility,” declared a third.

10

He possessed brawn and vigor too. He was said to be able to straighten a horseshoe with his bare hands, and during his absences from court he climbed the barren peaks north of Lake Como, crawling on all fours past huge rocks and contending with “terrible bears.”

11