Leonardo and the Last Supper (2 page)

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

This epitome of masculine pulchritude bore the grand title

pictor et ingeniarius ducalis

: the duke’s painter and engineer.

12

He had come to Milan, aged thirty, in hopes of inventing and constructing fearsome war machines such as chariots, cannons, and catapults that would, he promised Il Moro, give “great terror to the enemy.” His hopes were no doubt boosted by the fact that Milan was at war with Venice, with Lodovico spending almost 75 percent of his vast annual revenues on warfare. Although visions of battle danced in his head, he actually found himself at work on more modest and peaceable tasks, such as designing costumes for weddings and pageants, fashioning elaborate stage sets for plays, and painting a portrait of Il Moro’s mistress. He amused courtiers by performing tricks such as turning white wine into red, and by inventing an alarm clock that woke up the sleeper by jerking his feet into the air. Occasionally the tasks were mundane: “To heat the water for the stove of the Duchess,” one of his notes recorded, “take four parts of cold water to three parts of hot water.”

13

Despite his diverse assignments, over much of the previous decade Leonardo had devoted himself to one commission in particular, a work of art that should truly have sealed his reputation as an artist unrivaled by ancients and moderns alike. In about 1482, shortly before moving to Milan, he composed a letter of introduction to Lodovico, a kind of curriculum vitae

that somewhat exaggerated his abilities. In the letter, he promised to apprise Il Moro of his secrets, casually assuring him that “the bronze horse may be taken in hand, which is to be to the immortal glory and eternal honour of the prince your father of happy memory, and of the illustrious house of Sforza.”

14

This bronze horse was the larger-than-life equestrian monument by which Lodovico hoped to celebrate the exploits of his late father, Francesco Sforza. A wily soldier of fortune (Niccolò Machiavelli praised his “great prowess” and “honourable wickedness”), Francesco became duke of Milan in 1450 after overthrowing a short-lived republican government.

15

He was the son of a man named Muzio Attendolo who, as a youngster, had been chopping wood when a troop of soldiers rode by and, eyeing his brawny frame, invited him to join them. Muzio threw his axe at a tree trunk, vowing to himself: “If it sticks, I will go.” The axe stuck, and Muzio became a mercenary hired at various times by all of the major Italian princes. His strapping physique and fierce nature brought him the nickname “Sforza” (

sforzare

means to force), which, like the axe, stuck.

Francesco Sforza had been an equally brilliant soldier. He rose from soldier to duke nine years after marrying the illegitimate daughter of one of his clients, the duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti. The Visconti family had ruled Milan since 1277, and as dukes since 1395. However, in 1447, after Filippo Maria died without a male heir, the citizens of Milan did away with the dukedom and proclaimed a republic. Two years later, staking his claim to rule the city, Francesco blockaded and besieged Milan, whose starving citizens eventually gave up on their republic and, in March 1450, welcomed their former mercenary as duke of Milan. Francesco did not suffer the succession problems of Filippo Maria, fathering as many as thirty children, eleven of them illegitimate. No fewer than eight sons were born on the right side of the blanket, with the eldest, Galeazzo Maria—Il Moro’s older brother—becoming duke upon Francesco’s death in 1466.

The Visconti family had a gaudy history of heresy, insanity, and murder. One of the more intriguing members, a nun named Maifreda, was burned at the stake in the year 1300 for claiming she was going to be the next pope. Giovanni Maria Visconti, Filippo Maria’s older brother, trained his hounds to hunt people and eat their flesh. Filippo Maria, fat and insane, cut off his wife’s head. Even in such company, the cruel and lecherous Galeazzo Maria

stood out. Machiavelli later blanched at his monstrous behavior, noting how he was not content to dispatch his enemies “unless he killed them in some cruel mode,” while chroniclers could not bring themselves to describe various of his deeds.

16

He was suspected of murdering not only his fiancée but also his mother. In 1476 he was felled by knife-wielding assassins, leaving behind an eight-year-old son and heir, Giangaleazzo—the child duke elbowed out of the way, five years later, by Lodovico il Moro, who solved the problem of authority in Milan by decapitating the boy’s regent.

Lodovico’s claim to sovereignty was tenuous. Technically speaking, he was only the guardian and representative of his nephew, who had inherited the title of duke of Milan from his father. This dubious prerogative meant Lodovico was anxious to keep alive in everyone’s mind the memory of his own father. He had therefore commissioned from a scholar named Giovanni Simonetta a history of Francesco’s illustrious career. He was further planning to have heroic scenes from his father’s life frescoed in the ballroom of Milan’s castle. An equestrian monument of Francesco had been mooted as early as 1473, when Galeazzo Maria planned to have one installed before Milan’s castle. The project ended with his assassination but was revived by Lodovico, who envisaged the bronze monument as the most conspicuous and spectacular of the tributes to his father.

Mercenary captains were often flattered after their deaths in paint, print, and bronze. The sculptor Donatello cast a bronze equestrian monument of the Venetian commander Erasmo da Narni, better known as Gattamelata (Honey Cat), to stand in the Piazza del Santo in Padua. In 1480 another Florentine sculptor, Andrea del Verrocchio—Leonardo’s former teacher—began working for the Venetians on a statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni on horseback. Lodovico envisaged something even more grandiose for his father. As an ambassador reported, “His Excellency desires something of superlative size, the like of which has never been seen.”

17

Leonardo da Vinci once wrote that his first memory was of a bird, and that studying and writing about birds therefore “seems to be my destiny.”

18

Yet horses were truly the rudder of Leonardo’s fortune, and a horse was, in a manner of speaking, what had brought him to Milan in the first place. According to one source, in about 1482 Lorenzo de’ Medici, the ruler of Florence,

had dispatched him to Milan with a special diplomatic gift for Lodovico Sforza: a silver lyre that Leonardo had invented, and on which he could play, an early biographer claimed, “with rare execution.”

19

This unique musical instrument was in the shape of a horse’s head. A hasty sketch in one of Leonardo’s manuscripts shows what the instrument may have looked like, with the horse’s teeth serving as pegs for the strings and ridges in the roof of the mouth doubling as frets.

Given Lorenzo de’ Medici’s habit of conducting diplomatic relations through his artists, the story of the lyre has a ring of truth.

20

But lyre or no lyre, Leonardo almost certainly would have made his way north to Milan in order to build weapons or design the equestrian monument, opportunities he must have decided did not readily present themselves in Florence.

Leonardo received the commission for the bronze statue within a few years of his arrival in Milan. Lodovico revived the project in earnest in 1484, though Leonardo was not his first choice as sculptor. Despite Leonardo’s presence in Milan, in the spring of 1484 Lodovico wrote to Lorenzo de’ Medici asking if he knew of any sculptors capable of casting the monument. But Florence’s two greatest sculptors, Verrocchio and Antonio del Pollaiuolo, were both busy on other projects. “Here I do not find any artist who satisfies me,” Lorenzo regretfully replied. He did not endorse Leonardo, merely adding, “I am sure that His Excellency will not lack someone.”

21

For want of another candidate, then, Leonardo was given the commission, possibly quite soon after Lorenzo’s response. He attacked the project with relish, albeit evidently inspired much more by the figure of the horse than by that of its rider. He made a close study of equine anatomy, and even composed and illustrated a (now-lost) treatise on the subject. He spent hours in the ducal stables, scrutinizing and drawing Sicilian and Spanish stallions owned by Lodovico and his favorite courtiers. One of his memoranda reads, “The Florentine Morello of Mr. Mariolo, large horse, has a nice neck and a very beautiful head. The white stallion belonging to the falconer has fine hind quarters; it is behind the Porta Comasina.”

22

Leonardo’s statue would not simply be anatomically correct; it would also strike an energetically rampant pose. Donatello’s statue of Gattamelata portrayed the mercenary leader sitting upright on a placidly pacing horse, while Verrocchio’s—on which Leonardo probably worked for a year or two before leaving Florence—placed Colleoni astride a muscular beast whose left foreleg was held prancingly aloft. Leonardo planned something more astonishing, a horse rearing on its hind legs with its front hooves pawing the air above a prostrate foe. Furthermore, his statue would be enormous. Donatello’s monument was twelve feet high, Verrocchio’s thirteen—but Leonardo envisaged a statue whose horse alone would be more than twenty-three feet in height, three times larger than life. It would testify to the glory of Francesco Sforza but, even more, to the tremendous and unrivaled abilities of the artist himself. Designing and casting a bronze statue of such magnitude was unprecedented. One of his contemporaries wrote that the feat was “universally judged impossible.”

23

Leonardo, however, was never one to be daunted by colossal tasks. He once reminded himself in a note: “We ought not to desire the impossible.” Elsewhere he wrote, “I wish to work miracles.”

24

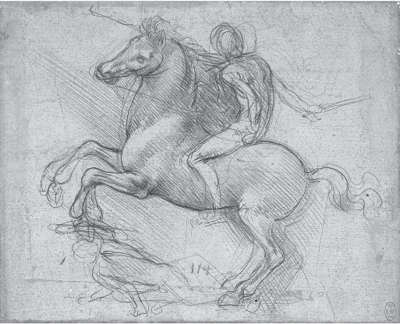

Leonardo’s study for the equestrian monument commissioned by Lodovico

The gigantic horse did appear to be, if not impossible, then at the very least complex and extremely challenging: something that would indeed take a miracle to perform. The project taxed even Leonardo’s ingenuity. Records do not show how far he advanced in these early years, but work certainly proceeded neither swiftly nor auspiciously. By 1489, Lodovico Sforza had

begun to doubt the wisdom of giving him the commission. As the Florentine ambassador to Milan wrote home to Lorenzo de’ Medici, “It appears to me that, while he has given the commission to Leonardo, he is not confident of his success.”

25

Leonardo had responded to Il Moro’s doubts with a spirited publicity campaign. In 1489 he asked a friend, the Milanese poet Piatto Piattini, for a poem celebrating the equestrian statue.

26

He clearly wanted to build enthusiasm for the project—and for his own ability to execute it—at a time when Il Moro was losing faith not only in his sculptor but also perhaps in the monument itself. Piattini duly complied with Leonardo’s request, composing a short poem that praised Francesco Sforza and extolled the equestrian monument as “supernatural.” He also produced a second poem exalting Leonardo as “a most noble sculptor” and comparing him to ancient Greek sculptors such as Lysippos and Polykleitos.

27

Piattini noted in a letter that though “keenly sought out” by Leonardo to produce a poem, he did not doubt that the artist had made the same request “to many others.” This may well have been the case: Leonardo was certainly mounting a vigorous offensive to keep his job. Around the same time another poet, Francesco Arrigoni, wrote a letter to Lodovico observing that he had been asked “to celebrate with some epigrams the equestrian statue.” His effort was much longer than Piattini’s, a series of Latin epigrams rhapsodizing both the bronze horse and its ambitious author, who was once again compared to the finest sculptors of ancient Greece.

28