Double Down: Game Change 2012 (76 page)

Read Double Down: Game Change 2012 Online

Authors: Mark Halperin,John Heilemann

Tags: #Political Science, #Political Process, #Elections

Mitt Romney. Romney began preparing for his October debates against Obama in June—and the hard work paid off with a game-changing performance in Denver.

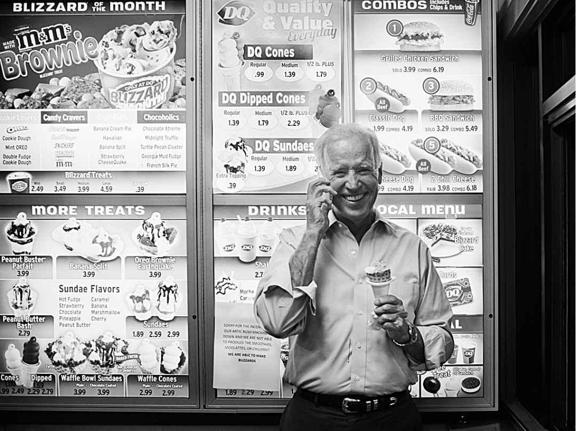

Joe Biden. Vice President Biden cultivated a warm personal rapport with Obama but still had to fight for a bigger role in the campaign.

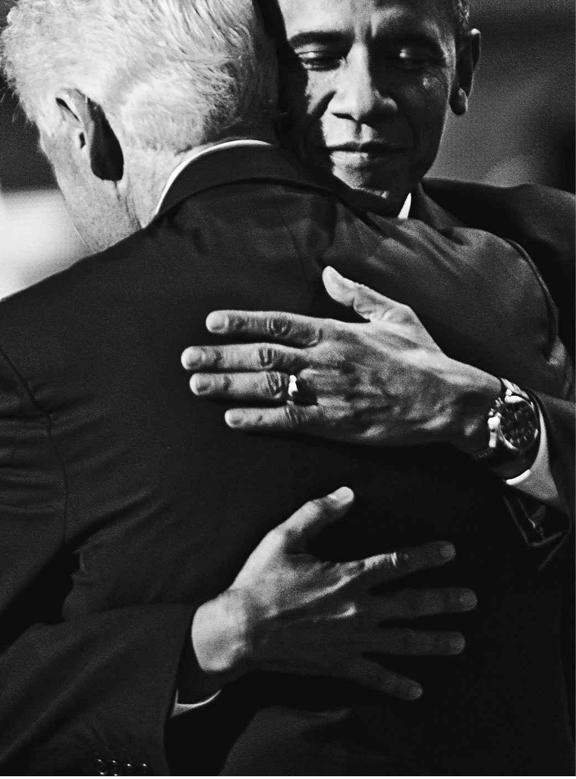

Barack Obama and Bill Clinton. Overcoming the mutual rancor of the 2008 campaign, the Big Dog made a strong case for Obama’s reelection on the stage at the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte.

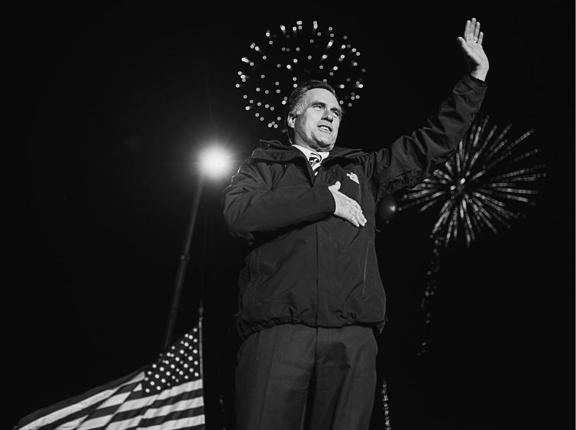

Mitt Romney. The Republican nominee had high hopes for his convention in Tampa, until it was rocked by a hurricane, speechwriting bedlam, and Clint Eastwood’s unexpected Dadaistic presentation.

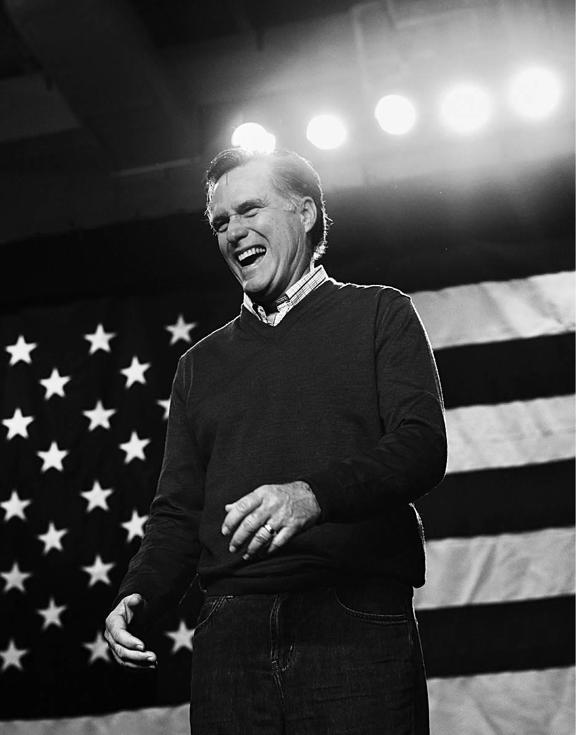

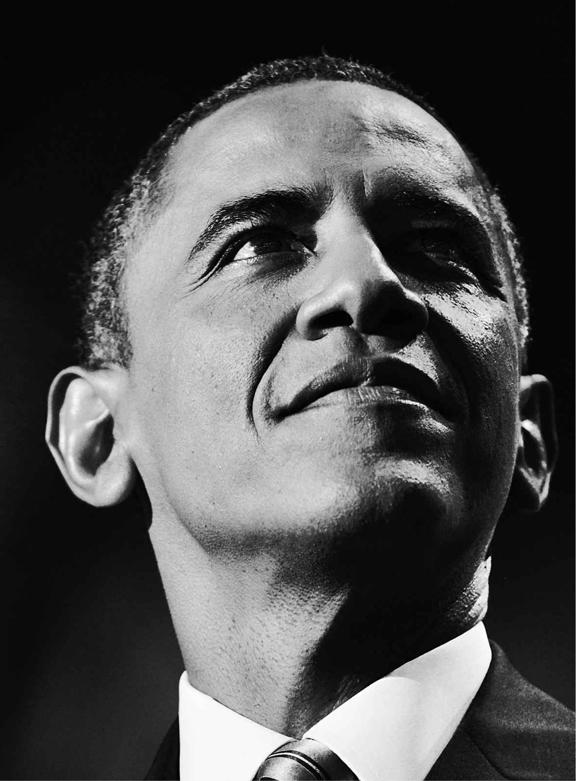

Barack Obama. At an election-eve rally in Des Moines, Iowa, an emotional Obama returned to the state that launched his 2008 campaign.

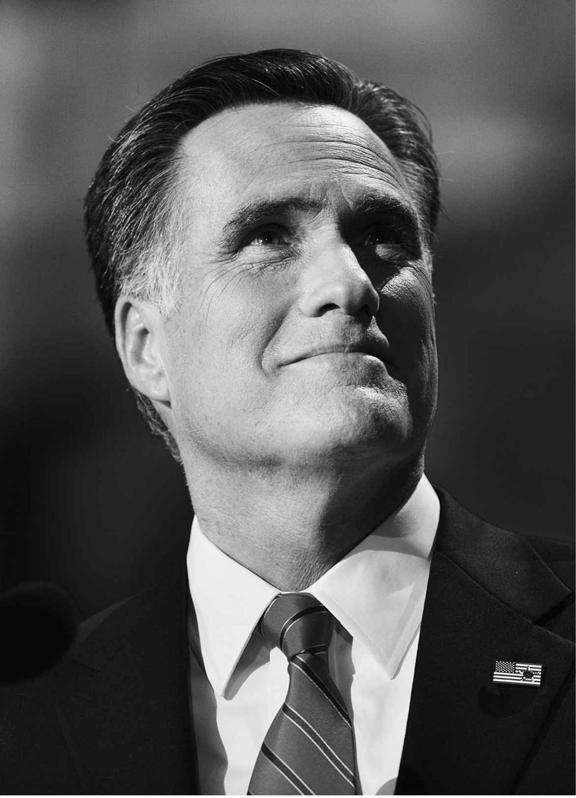

Mitt Romney. After decades of personal and professional success, Romney believed it was his patriotic duty to run for president. Up until the final hours of Election Day, he thought he would pull off a win.

Barack Obama. Obama considered his reelection victory in 2012 a far more satisfying and significant achievement than his win in 2008.

AUTHORS’ NOTE

This book is a sequel to

Game Change,

our account of the 2008 presidential election, in all the obvious ways, but also in its animating impulses, objectives, and techniques. Once again, the campaign we set out to chronicle had been covered with great intensity across a multiplying array of platforms. Once again, we were convinced that many of the stories behind the headlines had not been told. Once again, we have tried to render the narrative with an unrelenting focus on the candidates and those closest to them—with an eye toward the high human drama behind the curtain, and with accuracy, fairness, and empathy always foremost among our aims.

The vast bulk of the material in the preceding pages was derived from more than five hundred full-length interviews with more than four hundred individuals conducted between the summers of 2010 and 2013. Almost all of the interviews took place in person, in sessions that often stretched over several hours. (Beyond these marathon sittings, there were countless telephone and e-mail conversations to follow up and check facts.) Many sources also provided us with e-mails, memos, notes, journal entries, audio and video recordings, and other forms of documentation. Only a handful of people declined our requests to participate.

All of our interviews for the book—from those with junior staffers to those with the candidates themselves—were done on a “deep background” basis. We took great care with our subjects to be explicit about what this term

of art meant for this project: that we were free to use the information they provided (once we had determined its veracity) but that we would not identify them as sources in any way. In an ideal world, granting such anonymity would be unnecessary; in the world we actually inhabit, we believe it is essential to elicit the level of candor on which a book of this sort depends.

Inevitably, we were called on to compare and reconcile differing accounts of the same events. But we were struck by how few fundamental disputes we encountered in our reporting. In almost every scene in the book, we have included only material about which disagreements among the players were either nonexistent or trivial. Regarding the few exceptions, we brought to bear deliberate professional consideration and judgment.

In reconstructing scenes and conveying the perspectives of the participants, we relied exclusively on parties who were directly involved or on those to whom they spoke contemporaneously. Where dialogue is within quotation marks, it comes from the speaker, someone who was present and heard the remark, notes, transcripts, or recordings. The absence of quotation marks around dialogue indicates that it is paraphrased—meaning that our sources were in agreement about the nature, texture, and substance of the statement, but there were minor divergences regarding precise wording. Where thoughts or feelings are placed in italics, they come from the person identified or others to whom she or he expressed her or his state of mind.

The interviews for

Double Down

were all governed by a strict embargo, meaning that we agreed to use the information we obtained only after Election Day and only in the book. In a few instances—including, notably, the episode described in Chapter 3 revolving around Obama’s list, in which we were the book authors to whom the items on the list were disclosed, shortly after the president shared the contents with his team—our reporting efforts became part of an unfolding story. But that in no way affected our commitment to the embargo. At the same time, our reporting and writing here was grounded in our daily and weekly coverage of the campaign for our respective magazines; a number of passages in the book are drawn from that work.

—Mark Halperin and John Heilemann

September 2013

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A project of this size and duration leaves its perpetrators feeling a little like a tin-pot Greek bank, its balance sheet littered with more towering debts than could ever be repaid in this life or the next.

Our first and most titanic IOU is to our sources, who spent endless hours with us in person and on the phone. We thank them immensely for their generosity, trust, and patience. Big ups also to their assistants, who facilitated many of the interviews.

We are grateful to our incomparable literary agent, Andrew Wylie, who always knows when to hold ’em and doesn’t really comprehend the concept of folding ’em. His team at The Wylie Agency fielded our requests with speed and a smile. In a previous life, Scott Moyers was part of that team. It was kismet and our great good fortune that, just after we signed on at The Penguin Press, Scott became the imprint’s (and therefore our) publisher.

Ann Godoff, our editor, has earned a reputation as the best in the business: savvy, eagle-eyed, tough-minded yet nurturing, committed above all and before everything to the quality of the words on the page. And, whaddya know, it’s true! We were blessed to have her and all the other tremendously talented Penguiners—including Elisabeth Calamari, Tracy Locke, Will

Palmer, Lindsay Whalen, and Veronica Windholz—on our side from start to finish.

Special thanks as well to Chris Anderson, whose genius with a camera is evident in the book’s photo insert; to Jane Rosenthal, for a timely homestretch maneuver on our behalf; and to Elizabeth Wilner of Kantar Media’s Campaign Media Analysis Group.

Many of our journalistic colleagues produced terrific coverage of the campaign and its dramatis personae. We benefited in particular from Dan Balz’s book

Collision 2012: Obama vs. Romney and the Future of Elections in America;

Politico’s series of election e-books,

The Right Fights Back, Inside the Circus, Obama’s Last Stand,

and

The End of the Line;

Jay Root’s e-book

Oops!

, on Rick Perry; Bob Woodward’s

The Price of Politics,

on the debt-ceiling drama of 2011; Ariel Levy’s “The Good Wife,” on Newt and Callista Gingrich, from the January 23, 2012, issue of

The New Yorker;

Robert Draper’s “Building a Better Mitt Romney-Bot,” from the November 30, 2011, issue of

The New York Times Magazine;

and Benjamin Wallace-Wells’s “George Romney for President, 1968,” from the May 28, 2012, issue of

New York

magazine. More generally, we gleaned much from the reporting and analysis of Mike Allen, Matt Bai, David Chalian, David Corn, John Dickerson, Joshua Green, Maggie Haberman, John Harris, Vanessa Hope, Jason Horowitz, Al Hunt, Gwen Ifill, Jodi Kantor, Joe Klein, David Maraniss, Jonathan Martin, Adam Nagourney, Jim Rutenberg, Roger Simon, Ben Smith, Glenn Thrush, Jim VandeHei, Judy Woodruff, and Jeff Zeleny.