Dr. Pitcairn's Complete Guide to Natural Health for Dogs and Cats (42 page)

Read Dr. Pitcairn's Complete Guide to Natural Health for Dogs and Cats Online

Authors: Richard H. Pitcairn,Susan Hubble Pitcairn

Tags: #General, #Dogs, #Pets, #pet health, #cats

Though the signs are not specific, cats having this problem will stop eating and may have vomiting. A thread caught up around the tongue is very difficult to see. Just opening the mouth may not show it; a needle caught somewhere in the throat or esophagus will show up on an x-ray, as will bunching of the intestine.

Be on the lookout for ways your pet could

ingest the many poisonous materials found

in most homes.

This ingestion could occur unintentionally (through skin or paws) or out of curiosity (through chewing or swallowing). Most homes contain numerous poisonous substances, from toxic houseplants, antifreeze, insecticides, and drugs to caustic cleansers and mothballs (beware of letting a cat sleep in a closet or drawer full of these little buggers—rather, debuggers). The challenge for you is like the one parents of toddlers face. See chapter 8 for more detailed coverage of dangerous substances.

Make a habit of glancing in your car, tool

shed, garage, oven, refrigerator, dryer, or

any drawer, cabinet, or closet before closing

it.

Your curious cat may have jumped inside when you weren’t looking. Such oversights can be fatal.

Take care that your animal does not chew

on electric cords.

Don’t confine a puppy or kitten in a room with an exposed cord. Reprimand it firmly if you catch the animal chewing on or playing with one.

Also make sure that your pet doesn’t chew

up and swallow inedible objects like newspapers,

books, plastic toys, or bags and other

such things.

A rawhide bone makes a good substitute chewing toy.

If you have toddlers, make sure they don’t

handle a small animal too roughly, because

that endangers both parties.

Also, the child may unintentionally cause a great stress for an animal by making a loud noise near its sensitive ears.

If a child is responsible for taking care of

a pet, make sure the job gets done the same

way you would do it, every day.

Don’t let the animal become the victim of a learning experience in “natural consequences.” Teach your child the necessity of sticking to any responsibility he or she has assumed for an animal.

If you live in an upper-floor apartment

(second floor and up), screen your windows.

Despite their agility, cats can and do fall out of windows and off balconies. Many of my clients in New York City lost cats this way.

By taking these precautions and by adopting an overall attitude of watchfulness and consideration, modern life need not hold undue peril or stress for your animal or for you; instead, it can provide unique opportunities for adventure and enjoyment.

SAYING GOOD-BYE: COPING WITH A PET’S DEATH

T

he evening wore on, the music from the radio drifting out and enveloping us all. And with each moment, my wife and I could see that the small black kitten she held in her lap was edging even closer to death. Only a week before, we had adopted her from the animal shelter clinic where I had twice saved her life—first from the ravages of parasites, and then from the institutional procedures that required unadopted strays to be put to sleep after a certain period.

But now further postponing seemed impossible. I had done what I knew how to do and yet Miracle, as we’d dubbed her on

account of her heroic, though brief, rebound, was surely on her way out.

The signs were clear. Her small body grew steadily weaker and limper and her legs began to stiffen. Her eyes stared, dilated and motionless, fixed upon some awesome eternity. Occasionally she waved her head in small convulsions and feebly licked the inside of her mouth.

We had already discussed the possibilities. We could have struggled to save her all the way up to the end, violating her dignity with needles, tubes, and drugs. Or, to spare her—or maybe ourselves—the drawn-out process of dying, we could have injected her with the standard euthanasia solution, a painless passport to a quick end. Yet somehow, in that situation and with that animal, it just seemed right to let her go in her own way.

Without having to talk about it, we both knew it would be best this way. Looking at her, we realized how little we knew about the mystery of death or of life. We didn’t know who or what a cat was, really.

We didn’t know from where she had come or to where she would go. Yet we knew that beneath our surface differences there is a oneness, a bond uniting all living creatures.

We knew that soon this graceful, highly evolved body with its tiny, perfect eyes would return to the earth, never to fulfill its promises. We thought of how we would miss her innocence, her playful grace, her courage—and a wave of sadness swept over us. Yet, what must be must be. And it was all right to be as it was.

We placed her into her sleeping box atop some warm bottles covered with cloth and settled into bed. Gently and slowly, the darkness began to lower us into that unknown into which we all go each night. Through the growing silence there came a few indescribable sounds—long, low half-groans, half-meows. We reached over and felt Miracle’s temperature. It was dropping.

Once, in the middle of the night, we awoke to hear another of the strange sounds, this one deeper, longer, with an air of finality.

The sunlight was streaming through the window when we awoke that morning, full of a fresh appreciation for the gift of living. We got up and looked in Miracle’s box, knowing what we would find. She was indeed gone now. Her body was rigid and cold. Her eyes and mouth were open, frozen as if in surrender to some great force that had passed through her.

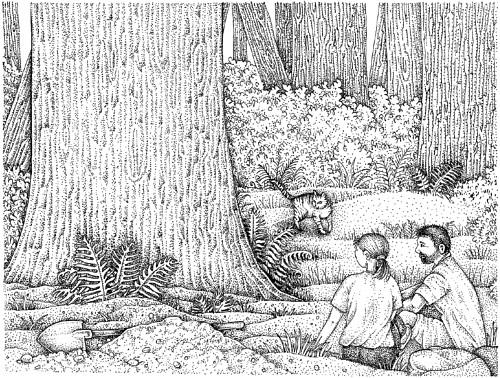

We found the right place to bury her, beneath a towering redwood on the edge of a nearby forest. We dug a small hole at the foot of the tree and then simply sat, silently.

The redwood was magnificent, sparkling and waving in the morning light, surging up from the earth to the sky. Into this great tree something of our small friend would pass. From form to form, life would go on. We laid her body in the soil, covering it over with the tree’s roots and the sweet-smelling forest loam. As we tamped down the last of it we heard a small rustling in the bushes. We turned to see.

It was a cat, watching.

THE CHALLENGE OF DEATH

Often we think of death as something to fear, to put out of mind and avoid at all costs. Yet in the end it comes to all organisms. It will come to your animal, and one day it will surely come to you and me.

But as the passing of Miracle and of others we have known has taught us, death need not be feared. In fact, to be fully present with it and let its significance speak to you, you can make such an experience a thing of beauty. It can remind us, if we have forgotten to notice, just how mysterious and wondrous life truly is.

That is why it saddens me when I see and hear from so many people who are deeply burdened and upset at the anticipation or the memory of a pet’s death. Their grief is real—often as great as or greater than that felt at the loss of a human friend or relative.

For others, however, the temptation is to just “stuff” their feelings inside and not really experience them, an understandable response. But because they are unwilling or unable to face their feelings and thus learn from them, people shut themselves off not only from the pain of death but also from its beauty and meaning. But facing our emotions can provide real opportunities for learning and flowering.

A pet’s death can be a complex thing. All sorts of emotions can arise, including sadness, anger, depression, disappointment, and fear. With people for whom the relationship is especially important—such as a single person, a childless couple, or an only child for whom the animal has been a best friend—the grief may be that much greater. And, too, if the death was sudden and unexpected, or if it seemed preventable (as in an accident), the feelings of loss and disappointment can be particularly intense.

In addition to those psychological hurts common to losing either a human or an animal companion, a pet’s death brings it own unique challenges. For one thing, the euthanasia option can burden the owner with a difficult decision. Another problem is that it is not socially acceptable to mourn openly over an animal, although the grief may be just as real as if you had lost any other family member. It might be hard to find a sympathetic listener to help you work through the experience. And even sympathetic employers are unlikely to allow absence from work for mourning a faithful cat or dog.

In fact, it

is

socially acceptable to replace the lost pet with a new one immediately after death. If a woman were to remarry the day after her husband’s funeral, however, eyebrows would be raised. Simply replacing your last pet with a new one will not heal the grief you feel. Only time and insight can do that. And parents who rush out to buy a new pet for their bereaved child before she has really said goodbye to one just lost should realize that the unspoken message can be: “Life is cheap; relationships are disposable and interchangeable.”

HANDLING GRIEF

Above all else, you need to know how to cope with the grief and other emotions that may surface before, during, or after death. If you can do that, any choices or actions required of you will come much more easily.

Lynne De Spelder, a friend who teaches, counsels, and writes on the subject of death and dying, emphasizes that coping with an animal’s death is much the same as coping with the loss of a human friend: “It’s really important to

handle

the grief. Research has shown the costs of mismanaged grief can be great, [such as] illness among survivors, for example. Hiding from grief makes it worse.”

How can you handle it? Start with the most important thing: Give yourself

permission

to grieve. Lynne observed, “Women often deal with grief better than men simply because they are allowed to cry. Also, it’s good to find someone who’ll listen. If your spouse won’t, find someone who will. If someone makes light of your grief, it’s probably his own fear of emotion.”

Suppose your crying and sadness seems to go on too long? That’s a signal that you are dwelling too much in your thoughts and memories. Lynne and other grief counselors encourage people suffering from loss to discover and engage in nurturing activities—such as yoga, hiking, music, or sports—that help people to lovingly let go of the past and to open themselves to the goodness of the present.

From my experience of loss, I think there can be a certain resistance to letting go of these thoughts, even though we may agree it would be the healthiest thing to do. If the relationship has been close it can almost feel like a betrayal of that closeness to stop thinking about it. It becomes sort of an expression of loyalty that we hold onto the feelings and memories. To get beyond this, we have to realize that our lives would just come to a stop if we never got over the losses that life will undoubtedly bring us. I can still know that I loved the person or animal in my life; that will never change. It isn’t a betrayal of them to carry on with what it is we have to do and with our own lives.

HELPING THE YOUNG CHILD

When you must help a child cope with the loss you all feel, it’s important to first understand your own feelings. You must be honest and open about what happened. But don’t try to console the child with an instant replacement or with explanations that can be misinterpreted or taken too literally, such as “he went away” or “she was taken to Doggie Heaven.” If the child wants to see the dead body before burial, understand that it is a natural curiosity and should be allowed, provided you are emotionally stable about it yourself.

Talk with the child and make sure he is not harboring misunderstandings. Don’t let him blame himself or even you for the death. If you had the animal put to sleep because it

was clear that a painful death was inevitable, say so, and give the child a chance to understand. It helps to communicate your own dilemma, that you “did not know what else to do.” It is a common human situation to have to act in the face of uncertainty and there is no shame in doing so.

THE ISSUE OF GUILT

I have been on the listening end for many, many people who have lost animals. Sometimes, with someone I know well, I have asked them more about their feelings. “What are you feeling the most about losing them?” or “How do you feel about how things went?” referring to their choice to use alternative forms of medicine instead of the usual conventional approach.

I am really surprised at the answers I get. The most common response I hear is that “I should have done more.” Now of course this is always possible, that one could have done more, but I will hear this statement even from the

most devoted people you can imagine

. It can be someone that cared for a dog that could not walk or control their bowels, and for months they have been carrying them in and out, cleaning up after them all that time. These are people that

have spared nothing

in their nursing care. So I wondered, “How could they feel they had not done enough?”