Drama (26 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

Two Times Above the Title

In the 1970s I was no Broadway star. In twelve shows, I was billed above the title only twice. Once was for

My Fat Friend

(below Lynn Redgrave and George Rose, and in letters half their size). The other was for Eugene O’Neill’s

Anna Christie

(well below the name Liv Ullmann). In each of the other ten productions, I was a member of an unbilled ensemble. This suited me just fine. I loved the company spirit that prevailed in shows like

Comedians

,

Trelawny of the “Wells,”

Spokesong

,

Once in a Lifetime

, and Arthur Miller’s

A Memory of Two Mondays

. Even my Tony Award for

The Changing Room

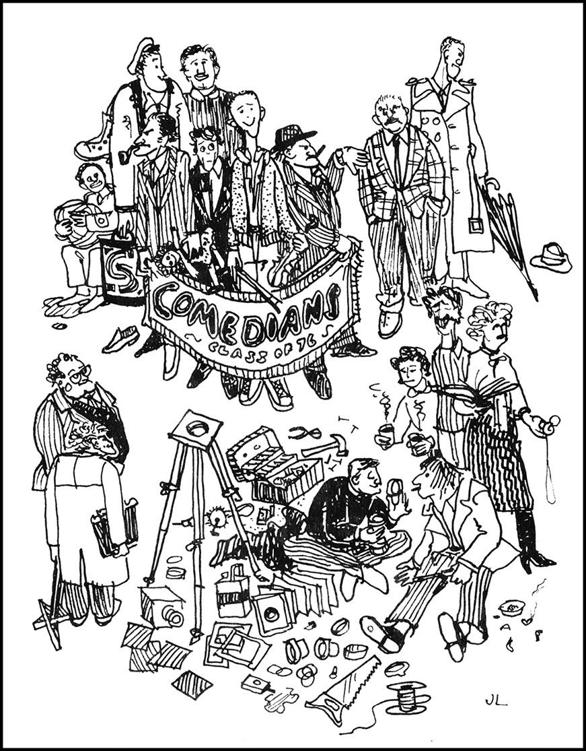

was for “best featured actor” in a selfless twenty-two-man ensemble. In all of those shows there was rarely a sense of hierarchy, rarely an ego trip, rarely a catfight over prerogatives. My memories of those ensemble shows are packed with episodes of the kind of company spirit and moist sentiment that can only be generated inside a theater. Every opening night was a flood of congratulatory gifts (by tradition, mine has always been an inscribed caricature of every member of the cast and crew). At every performance that fell on New Year’s Eve, the cast linked arms at the curtain call and led the audience in “Auld Lange Syne.” Every Christmas featured an elaborate backstage game of “Secret Santa.” When we had to perform a matinee and an evening show of

Comedians

on Christmas Day of 1976, Rex Robbins (the beloved

Changing Room

alum with the enormous testicles) swung into action. He organized a potluck supper between shows for the entire cast and crew and their families. He decorated the basement under the stage of the Music Box Theatre. He even installed a Christmas tree. And he himself performed the role of Santa Claus for all the children. Of such moments, sweet memories and lifelong friendships are forged.

For me, that is the essence of the theater. For all the pleasures and perks of the movie business, it can never achieve the theater’s sense of community or its ineffable

esprit de corps.

Neither can television. A sitcom like

3rd Rock

bears a lot of resemblance to the world of theater—a long run, a tight-knit company of actors, a collaborative rehearsal process, a creative interaction with writers and directors, even a live audience. But it can’t touch the theater for selflessness, ensemble teamwork, and generosity of spirit. A soundstage is nothing like a backstage. A wrap party is nothing like a cast party. The honorifics of the theater are quaint and archaic, with few price tags attached—a backstage visit from Paul Newman, a portrait on the wall of Sardi’s, a

New York Times

caricature by Hirschfeld (of which I received a grand total of eight). By contrast, the blandishments of success in film and TV seem crass and garish. The money is so lavish, the celebrity is so outsized, the competition is so keen and so public that a rigid hierarchy inevitably asserts itself. I love to work in film and television. I can’t imagine my career without them. But after a few too many soundstages and shooting locations, a few too many makeup chairs and craft service tables, a few too many early calls and queasy naps in overheated trailers while waiting for the next camera setup, it’s only a matter of time before I come running back into the arms of my old friends in the New York theater.

I

’ve had hundreds of those friends. Let me tell you about four of them.

Comedians

is a corrosively serious play. It throbs with anger and political heat. Its author, the English playwright Trevor Griffiths, is a near-revolutionary zealot, wielding theater as a club to smash down what he sees as Britain’s smug, complacent class system. Yet

Comedians

is about comedy, too. It crackles with edgy laughter. It is a compelling, unsettling blend of fizzy gags and harsh drama. I acted in it for four months in 1976.

The setting of

Comedians

is a dank grade school classroom in Manchester, in the north of England. On a rainy evening, a group of six working-class men straggle in. They are attending an adult education class in stand-up comedy led by an old-time music hall comic with the gravitas of a stern university professor. He takes the class through a series of warm-up drills in preparation for a comedy competition the men will attend later that evening. Act II is the competition itself, where each of these men presents his carefully crafted stand-up routine at a nightclub. In a canny piece of stagecraft, the theater audience becomes the audience for the competition. In front of the crowd, some of the would-be comedians kill. Some of them die, glazed with flop sweat. Act III is the aftermath of the competition, back in the classroom later that night. The centerpiece of this final act is a long, polemical argument in the empty room between the old comic and his prize pupil. The pupil is a dark, angry, genius comedian named Gethin Price. In our production, Gethin was brilliantly played by Jonathan Pryce, the young actor who had created the role in England the year before.

True,

Comedians

has its hidden political agenda. But it is dangerously funny and it buzzes with ideas about performance, ambition, social resentment, and rage. In an instance of life imitating art, our director was himself a master of comedy. Our rehearsal period with him was an ongoing master class in the art and craft of making people laugh. Years before, this man’s own work as a comedian, together with the likes of Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, and Shelley Berman, had helped to revolutionize the genre. Since then he had evolved into one of our finest directors, for both stage and film, winning a trunkload of Oscars and Tonys. He was also hilarious fun to work with. With improvisational glee, he took the all-male cast through his own set of comedy drills, striving to put us all in touch with the comic’s urge to amuse. These exercises went on for days, long before he began to actually stage the play. He held group sessions in which we would all take turns telling our favorite jokes. He conducted improvs, giving all of us the intense experience of both succeeding and failing at being funny. He told vivid, self-mocking stories of his own history as a performer. He played recordings of great comic monologists (for the first time I heard the voice of the amazing Ruth Draper). And he brilliantly dissected the nature of comedy itself—its components of hurt, need, and anger—and impressed on us his own deeply held belief that comedy is a serious matter.

Comedians

had a respectable run, but it wasn’t a hit. Its startling mix of comedy and rage was a bitter pill for Broadway audiences, and a lot of theatergoers must have expected something very different from a director who had won four Tony Awards for staging the plays of Neil Simon. As for the director himself, we could all see by the time we opened that

Comedians

had been a disappointment to him. The production hadn’t lived up to his hopes and he blamed himself for its shortcomings. But for me, working with him was inspiring, revelatory, and ecstatic fun. He is high on the list of the best directors I have ever worked with, or ever will. He was Mike Nichols.

I

left

Comedians

early to begin work on a major Broadway revival of Eugene O’Neill’s

Anna Christie

. The Norwegian star Liv Ullmann was to play the title role. Our director was José Quintero. José could not possibly have been more different from Mike Nichols, but his status in American theater was equally lofty. Where Mike was dry, ironic, and devilish, José was an active volcano of passion. He was a transplanted Panamanian who, years before, had embraced Eugene O’Neill as a kind of spiritual savior. He directed O’Neill’s plays with a Holy Roller’s messianic zeal (and he directed them nineteen times). He even claimed to converse with the dead playwright’s ghost.

I was cast opposite Liv as a seagoing Irish coal stoker named Mat Burke. In the play, Anna Christie has come home to her father’s barge, moored at a New York dockside, to leave behind her wretched life of prostitution. Out at sea, in Act II, father and daughter rescue Mat from a shipwreck and take care of him onboard the barge. As the story unfolds, Mat falls hard for Anna and asks her to marry him, never knowing of her shameful past. When he learns of it in the last act, the devout Catholic stoker is consumed with anger and humiliation. It doesn’t help when he discovers that Anna was brought up Lutheran. Anna desperately tries to persuade Mat that his love has cleansed her and that she is worthy of him. In a scene of near-Wagnerian passion, Mat kneels with her and asks her to affirm the truth of her protestations by swearing on his dead mother’s crucifix. The crucifix hangs on a chain around his neck where he had promised he would always wear it.

To stir us to an emotional pitch for such scenes, José periodically resorted to a kind of Pentecostal style of directorial invocation. In one rehearsal, five actors were running through the opening minutes of the play in which the bedraggled Anna staggers into a tavern. I was not in the scene, but I sat to the side, watching the action. On her entrance Anna croaks her famous first line:

“Gimme a whiskey, ginger ale on the side. And don’t be stingy, baby.”

Halfway through the scene, José stopped the action. We all sensed that one of his arias was about to begin. With a hypnotic glare, he focused his attention on Liv. Starting slowly, he began to create for her a detailed portrait of the debased life of a dockside prostitute. As he continued, his eyes widened. His face contorted. Spittle collected on each side of his broad mouth. His rich, accented voice rose, trembled, and broke with sobs. Steadily gathering steam, he spoke for at least fifteen minutes. He invoked scenes of his youth in Panama City, when great naval ships would dock there. He painted extraordinary verbal pictures of the streets of the city, “WHITE with SAILORZ!” He described hundreds of them lining up outside the bordellos.

“And they would go EEN! And they would come OUT!” José cried. “And each had their NEEEDZ and their PERVERSIONZZ!”

All of us sat there transfixed. Reaching a climax, he grabbed a ten-dollar bill from his pocket and thrust it into Liv’s hand.

“THERE!” he roared. “You are MINE. I have BOUGHT you!”

He proceeded to push and tug her around the room. Finally he thrust her in a corner where she cowered near tears.

“NOW,” he ordered at last, looming over her. “Start the scene AGAIN!”

When José directed the moment with Mat’s dead mother’s crucifix, he unleashed another of his inspirational perorations on me. At its height he tore a chain from around his neck. On it hung a crucifix. With tears in his eyes he told me that it was

his

mother’s crucifix, which she’d given

him

before

she

died. Just like Mat’s mother, she had begged José to always wear it. He snatched my prop crucifix from me and strung his mother’s around my neck. He told me to repeat the scene, armed with this sacred talisman. Maybe the crucifix worked a little magic. Maybe the scene played a little better the next time through. But José’s mischievous partner, Nick, told me later in confidence that José’s mother was still alive, happy, and well. She was living in the comfortable house José had bought for her back in Panama City.

“And, by the way,” Nick added, “that crucifix doesn’t belong to him.”

Anna Christie

was hardly my finest hour. Nor Liv’s. Nor José’s, for that matter. And it is curiously absent from most of our résumés. The play is ungainly and long, and our leaden production didn’t do much to help it out. Liv was a little too stately for her part, and no one would ever mistake me for a coal stoker (

Times

critic Walter Kerr was right when he claimed that I played Mat Burke as though I’d “been spun from a children’s merry-go-round”). The performances were exhausting, yet they rarely earned us more than a tepid response from the crowds. Indeed, the most memorable moment of our run was on one sultry July night when the massive 1977 East Coast blackout struck in the middle of one of my interminable Act III speeches. I suspect that a lot of people in the audience that evening were hugely relieved that the show came down an hour early. But if the show was far less than triumphant, there was one major compensation. The experience of working with José Quintero, that big-hearted, larger-than-life, pounding steam engine of human emotion, did not completely make up for those six months of depletion and disappointment. But it helped.