Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (41 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

The Biggest Show of Stars opened in Norfolk, Virginia, on April 5 (“for the first time in ‘package show’ history,” the city’s black weekly proudly announced, “a really big-time unit has elected Norfolk as its kick-off city”), after a couple of days of rehearsal in New York. The troupe was traveling on “buses, Cadillacs, planes, etc.,” according to the

Norfolk Journal and Guide,

which quoted a spokesman for the production company as saying, “If the show is a hit in Norfolk, it stands better-than-average chances of being a smasheroo elsewhere.”

The news of Sam’s settlement with Connie Bolling, the source of the “fornication and bastardy” charge that had landed Sam briefly in jail in Philadelphia, was just being reported in black newspapers all around the country. It was the first time that his arrest the previous December had been publicly revealed or, in fact, that there had been any news of the lawsuit at all. The settlement was for “well over $5000,” the

Philadelphia Tribune

reported in a headline story on April 1. His lawyer would concede only that Sam had agreed to the payment to “avoid a long and expensive court battle which might damage his career,” but there was no question that the child was his—Sam had had Crain check it out, and at this point he just wanted to put the whole sorry mess behind him.

Feld’s regular backup band, Paul Williams and his newly crowned Show of Stars Orchestra (Williams was the originator of the huge 1949 r&b hit “The Hucklebuck,” and a New York studio stalwart), provided solid instrumental backing, but Clif grumbled just as much about having to teach them Sam’s arrangements as he would have about working with any other group of musicians who did not play exclusively for his employer. “I carried a great big old suitcase full of arrangements, two of them, in fact. There was enough acts on the show to go for almost three hours, and when it was time for Sam to go on [at the end, after Clyde McPhatter and Paul Anka, the two acts that Irvin Feld personally managed], you’d just go out onstage, work your way through the amps, and plug in.” It was something of a comedown for someone who had performed with the Mills Brothers on stages around the world, but he believed in Sam, Sam treated him and everyone else around him with the utmost courtesy and financial consideration, and Sam was the star of the show.

In Philadelphia they drew less than one thousand, with Philadelphia’s most popular black DJ, Georgie Woods, MCing the show. Without any question the economy was a factor, maybe the bad publicity about the paternity suit contributed, but clearly the single element that cut most directly into box-office receipts was the fact that the Alan Freed package—with Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, Frankie Lymon, and Ed Townsend, among others—had played Philadelphia just eleven nights earlier, and Ray Charles was coming through with his own self-contained show in nearby Chester two days later.

They did good business and bad business. In New Haven, Frankie Avalon was hailed by

Billboard

reporter June Bundy as the star of the show, and Feld’s directive to the performers to “play down suggestive gestures and material” amidst the “powder keg” atmosphere of the crowd was approvingly noted by Bundy. Sam, Clyde McPhatter, and LaVern Baker were hailed as the “most showmanly,” and indeed, in city after city the nonstop revue came to be seen as something of a personal contest between Clyde and Sam, two pure stand-up singers who captivated the house each night not with steps, acrobatics, or gyrations but strictly by the intricate arrangement of their art.

Clyde certainly possessed the voice, the background, and to some extent even the temperament closest to Sam’s. Born in 1931 in Durham, North Carolina, to a minister father whose ten children all called him “Bishop” and a mother who lived for her children, he had moved to New York with his family at an early age, forming a spiritual group with David and Wilbur Baldwin, whose brother Jimmy was a writer. It was while he was with this group, the Mt. Lebanon Singers, that he first came to the attention of Billy Ward, a musical martinet, who was in the process of putting together a new r&b group, the Dominoes, that would merge the styles of the Ink Spots, the Ravens, the Orioles, and the gospel quartets. Clyde first burst upon the national scene in 1951, in the same year and at the same age—twenty—as Sam, but with a succession of Top 10 r&b hits rather than spiritual numbers. His tremulous natural falsetto was able to tease a phrase in that familiar melismatic manner to the point that music historian Bill Millar would count out the number of notes to which he could draw out a single syllable (twenty-two) in an attempt to quantify McPhatter’s astonishing capacity to extend both meaning and emotional depth. Like Sam, he was quick to acknowledge his debt to Bill Kenny of the Ink Spots, but, also like Sam, he brought something of his own, in his case an undisguised vulnerability, the kind of soulful excess that could transform “White Christmas” into a prayerful plea.

He left the Dominoes in 1953 and quickly formed a new group, the Drifters, at the instigation of Ahmet Ertegun, for whose Atlantic label he would enjoy even greater success (and create even more widely known r&b standards) with such songs as “Money Honey,” “Such a Night,” and “Honey Love” while serving as the same kind of inspiration to the young white singer Elvis Presley that Bill Kenny had been to him. After a two-year stint in the army, he went out on his own, and in the past three years had enjoyed seven Top 10 r&b hits, all but one of which (a duet with Ruth Brown) charted pop. Every night he performed an array of these hits, including, typically, “Have Mercy Baby,” “Come What May,” and the soaring, gospel-based “Without Love,” which “left the audience,” as the

Houston Informer

reported, “gasping for more.”

It was a spirit of friendly competition, in which Sam, Clyde, and LaVern Baker, the irrepressible twenty-eight-year-old life force who had preceded Sam at Wendell Phillips High School by a year and started out her show-business career at seventeen as Little Miss Sharecropper, frequently sang spirituals in the locker-room dressing rooms of the arenas in which they played. LaVern, an uninhibited, cheerfully bawdy ball of fire both on and offstage, closed the first half of the show with her biggest hit, “Jim Dandy,” and was known, according to

Ebony,

for her “sexy gestures and daring body movements,” which included sticking her finger provocatively in her mouth and rolling her eyes. She was as likely to cuss out a fellow performer with a string of epithets few of her male co-stars could match as she was to sew a button on the shirt of one of the kids on the show. But she was as dedicated to her gospel roots as either of her co-stars, and, the

Norfolk Journal and Guide

reported in a syndicated story, “If they can get permission from their respective record firms, they want to turn out an album of their favorite gospel songs as a trio.” One night, the Everly Brothers, whose specialty was close country harmony and who currently had the number-one pop hit in the country with “All I Have to Do Is Dream,” walked into the dressing room while Sam and Clyde were singing. “It was the most spectacular thing,” said nineteen-year-old Phil Everly, “the two of them changing off, [they] were about the best I ever heard.”

What set Sam and Clyde apart from so many of the others, a quality remarked upon by both reporters and peers, was a sense of restraint, an impression of natural elegance and introspection that manifested itself in both their person and their art. What Sam found so compelling about Clyde, though, were his private views on a whole range of subjects, views that, while not altogether foreign to Sam, he had never heard so forcefully expressed.

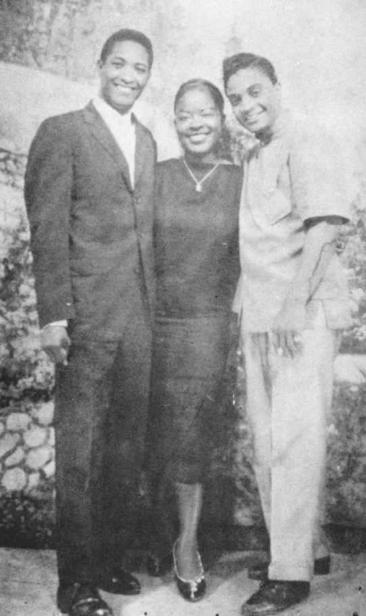

Sam, LaVern Baker, Jackie Wilson, 1958.

Courtesy of Reginald Abrams

Religion, for example. To Clyde, the kind of religion on which he had been raised was a swindle, “based on fear [and] hocus-pocus. You know, ‘God don’t like this, God don’t like that,’ so one day I said, ‘Goddamn it,’ and my father beat the hell out of me.” His father, too, the “Bishop,” he saw as something of a hypocrite and an oppressor, a man lacking in both sympathy and understanding, where his mother, a woman of little education but much “mother wit . . . never tried to hold me back.” He could always communicate with her, he said, because she supported his dreams. “She was a country girl [who] would say, ‘You can bring your biddies up, but once they learn to fly, you must let them use their wings.’”

He was a man with an acute sense of injustice, fully committed to the civil rights struggle, with a lifetime membership in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a willingness to make public gestures of support, as he had the previous Christmas when he was pictured in an ANP dispatch, mailing a box of records from his music shop in New Rochelle, New York, to the embattled black students of Little Rock. He was equally indignant at the inequities of the music business, racial and otherwise, and he railed quietly against the mistreatment that he had received at the hands of Atlantic Records.

All of this was so much against his perceived image that only an attentive listener would have picked it up, and many of his contemporaries missed it altogether. Clyde was shy, soft-spoken, polite almost to the point of diffidence, and because he liked his liquor, many of his fellow entertainers tended to dismiss his views or simply not to hear them. But he could have found no more attentive listener than Sam, who soaked it all up in much the same way that he took in all the information and opinions that he gathered from his wide-ranging reading, absorbing it all, trying out new perspectives, reserving judgment for another day.

There were other outstanding acts and personalities on the show. Sam could appreciate the pure pop sensibilities of some of the young white acts, like sixteen-year-old Paul Anka and eighteen-year-old Bobby Rydell, and he and Clyde would sometimes fool around with country tunes, which made perfect sense to the Everly Brothers, who recognized in their ornate vocal embellishments a striking resemblance to the way in which Lefty Frizzell, one of their idols in country music, would wrap his voice around a song. But the talent to which Sam was drawn most of all was twenty-four-year-old Jackie Wilson, who had emerged from a gospel background in Detroit to take Clyde’s place as lead singer with the Dominoes, then gone solo the previous fall at almost exactly the same time that Sam had emerged in the pop field. Wilson, a strongly extroverted personality who was crazy about both the Soul Stirrers and comic books, brought the house down every night with his opening set, which consisted entirely of his first two hit releases, “Reet Petite” and “To Be Loved,” complete with splits, knee drops, spectacular falsetto flights, and a sense of showmanship that never failed to electrify the audience. Offstage he was equally bold, brazen, and streetwise, with very much of a “player”’s personality, but for all of their differences, and for all of the smooth urbanity that he himself sought to cultivate, Sam was drawn to that, too.

T

HEY HIT CHICAGO

on May 3. Like the Alan Freed package the previous week, the Biggest Show of Stars was booked into the old Civic Opera House, where Sam had played the previous December. Once again the old neighborhood was out in force, and Jake Richard induced Sam to stop by Creadell Copeland’s house for an informal QCs reunion. None of the QCs had seen him perform—they all remained strict in their avoidance of secular music. Which bothered Sam in a way, even though he didn’t say anything. It kind of hurt the way the quartets would do him, he told Alabama Five Blind Boys guitarist Johnny Fields, who had come to see him three weeks earlier when the tour played Raleigh. “Sam had been in the gospel field, and he knew there weren’t no saints over there, either. He said, ‘I’m the same Sam Cook that was singing “Jesus Give Me Water.”’ He said, ‘I haven’t changed. I’m still Sam.’”

To the public at large he permitted no such glimpse of vulnerability. “The transition from gospel to pop tunes was easy,” he told an ANP wire service reporter backstage at the Civic Opera. “When I first started singing pop tunes, I wondered how my former associates and fans would react. But they accepted me, as I see them all sitting on the front row . . . just like they did when I was with the Soul Stirrers.”

That same night the violence that had been predicted by rock ’n’ roll critics since the start of both tours exploded at Alan Freed’s Big Beat show in Boston, when dancing broke out in the middle of Jerry Lee Lewis’ set and, after being stopped by police, broke out again during Chuck Berry’s performance. The show would not continue, the police announced, until everyone returned to their seats, and even then, the houselights would be left on as a security measure. “It looks like the Boston police don’t want you to have a good time,” Freed announced from the stage. Which was more than enough for the crowd, as the seventy-two-hundred-seat Boston Arena, primarily a hockey arena, erupted. Within a week Freed had been indicted by the Suffolk County D.A. for “inciting to riot” and fired from his job at WINS, as the tour itself came to an abrupt end. Universal Attractions’ R&B Cavalcade had already gone on permanent hiatus by this time, and the Dick Clark tour, which had been scheduled to begin at the end of the month, was almost immediately canceled.