Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (54 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

Jess was busy on a number of other fronts as well. Through Larry Auerbach he had made contact with Hugo and Luigi, two colorful first cousins who operated as a production team and had been hired by RCA earlier in the year (at the unheard-of sum of a million dollars over five years) to rejuvenate the company’s pop music department. Despite contractual guarantees of independence, they had trouble at first with RCA’s traditionally stodgy attitudes, but just within the last couple of months, they had had their first big hit on the label with Della Reese’s “Don’t You Know,” which not only reached number one on the r&b charts but eventually went to number two pop. It exemplified, said Luigi, the kind of hybrid sound typical of the Hugo and Luigi approach, an operatic adaptation of a Puccini waltz set to an r&b sensibility.

Hugo and Luigi (their last names were Peretti and Creatore, but everyone knew them by the more familiar appellation, which served as their production handle) were unashamed hitmakers and practical jokers for whom Jess had less than total respect because of what he took to be their somewhat crass view of both their business and their craft. On the other hand, Sam hadn’t really left him with a lot of alternatives. It would have been his personal preference to go to Atlantic. The label had a sterling reputation in the business, it was set up to do the kind of music Sam was best at, and, after losing Clyde McPhatter to MGM earlier in the year and having recently become aware that they were about to lose Ray Charles, their biggest star, to ABC, Atlantic’s owners, Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun, made Jess aware that there was almost nothing they wouldn’t do to get his client. But Sam wasn’t interested. Sam had heard from Clyde McPhatter that he had been treated with racial condescension and disrespect at Atlantic, and no matter how much Jess argued the point and reminded Sam that this was the music business, after all (“I said, ‘Maybe they’ll steal, but you’ll sell more records with them than with anybody else”), and that Ahmet and Jerry were liberals in good standing, Sam clung to his own view of the matter and flatly ruled the label out.

Jess would have approached Capitol, too, except that Capitol already had Nat “King” Cole, they would not go above a 3 percent ceiling on royalties, and they were adamant that Sam would have to split his publishing, something Jess understood was completely out of the question. So he was left with RCA, which was offering a 5 percent artist’s royalty, the same as Presley got, and would leave Sam’s publishing alone. Plus, Hugo and Luigi had agreed to include Sam’s guitarist, Clif White, on all his sessions, a nonnegotiable item from Sam’s point of view. So Jess moved from discussions with Hugo and Luigi into more formal business negotiations with newly promoted RCA vice president Bob Yorke, a straight shooter he had known for some time and always liked, and even though he would have preferred to have had more options, he made his points and listened to what Yorke had to say, following the principle that had guided him ever since he had first entered show business at the age of fifteen: make deals, don’t blow them.

On November 9

Billboard

ran an item disingenuously headlined “Hugo-Luigi Want Cooke” that reported on “the hottest rumor around the trade last week,” namely that “the hit-making a&r men at RCA . . . had made a fabulous offer to Sam Cooke to join the label after his Keen pact expires.” Even the size of the offer seemed designed to discourage literal interpretation, as a relatively modest proposal of $30,000 for a single year (with $20,000 of that against royalties), and another $30,000 (all against royalties) for a second-year option, was inflated to “a guarantee of $100,000, a rather sizable sum.”

With that, the fate of Keen Records as an ongoing label was to all intents and purposes sealed. Sam’s lawsuit up until this point had been proceeding in deliberate fashion, with motions and countermotions and moves for dismissal, but, as John Siamas now read the situation, with the RCA rumor out in the open, the distributors would simply stop paying, the money would dry up, and whatever chance there might have been for an amicable settlement, even a new start with Sam, was gone for good. The label had an album out on Sam called

Hit Kit,

a greatest-hits package that had been put together, as

Cash Box

presciently remarked, “for quick commercial consumption,” but even it stopped selling, and, while it would take another month before John Siamas threw in the towel, there was no question now, as John Siamas Jr. later observed, that his father simply “wanted to go back to the kind of thing that he had done professionally for twenty years [his aircraft parts business] and looked forward to doing again—and in an atmosphere that he, frankly, considered to be more ethical.” Siamas agreed to pay Sam a lump sum of $10,000 and transfer all song copyrights to him in exchange for Sam’s acknowledgment that this would stand in full payment of all artist royalties owed through June 30, 1959, as well as all songwriter’s royalties through the end of the year (in sum, close to $35,000). There were no bad feelings on either side, John Siamas Jr. felt certain. Keen, as his father saw it, simply “did not survive the record industry,” and while it continued as a catalogue label for the next couple of years (almost entirely

Sam’s

catalogue), John Siamas Sr. was not going to invest any more of his money in what he now saw as an essentially failed venture.

Sam was no less disillusioned in many respects with the business. Out on tour once again, he had decided to do without the services of William Morris, who he was convinced were no better than Bumps, just better educated and better able to get away with it. What had they ever done for him, he railed to Jess and his brother Charles, except sit on their ass and collect his money, money that he earned by the sweat of his brow? He was still pissed off about the Jackie Wilson tour. It would never have come about—and he would never have had to suffer the kind of humiliation that he did—if they had supplied him with the proper kind of bookings. And he was pissed off at what he took to be their dismissive attitude toward his pay: they sold him

like a slave

to Universal, they sold him for a pittance—$1,000 a night—and then they didn’t even concern themselves with how much more Universal was actually getting for his services. They told him they had talked Universal into splitting the commission—fuck that. They were all just making money off his back.

So he told Charles and Crain to go out and look for dates on their own. “Me and Crain got in the car, and we just drove. Stopped in places that looked like they could use a show. Then we find out who the promoter was in that town or whoever owned the biggest club—Crain knew most of them anyway, he had worked with them before, and he knew who to trust. We’d approach them, say, ‘We got Sam Cooke, and we want to come to you with a show.’ All down in Florida and Alabama and North Carolina and South Carolina. We never had no problem, man. Sam was trying to prove a point.”

Sam put it out in

Jet

magazine that he would be touring with L.C. “to help promote [his] career,” and that, in partial payment of the debt he owed his brother for “You Send Me” and all the other hits L.C. had written for him, he had now written a tune for his brother, which L.C. was scheduled to record. “Sam do what he want to do,” observed L.C., “and they be glad to get them dates, ’cause they knew they was going to make some money. Sam was different from everybody [else]. He didn’t care who he cussed out. He said, ‘I ain’t got to wait on nobody.’”

All of his loyalty, as Charles and L.C. saw it, was to the tight circle of family and friends around him. As far as Jess Rand went, “I didn’t know too much about Jess Rand,” said Charles. “Jess Rand wasn’t around us too much,” according to L.C. Crain was the only one functioning as any kind of manager. As much as Sam needed a manager. And Alex could call himself Sam’s

partner

all he wanted—he worked for Sam just like they did. Only they had known Sam longer. Sam didn’t trouble himself with such petty distinctions. He knew how everyone fit into his world—Bumps, the Soul Stirrers, the QCs, the Junior Destroyers, Duck, his brothers, even Rebert Harris, who was always going around boasting that he had taught Sam everything he knew. None of it affected Sam’s unwavering plan to move ahead with his life, to improve himself and his situation in every way that he could—but at the same time, it seemed like he felt responsible for them all somehow. Or maybe he saw them as responsible for him. It was as if he were determined to leave no part of himself behind—unlike Sammy Davis Jr., he would always mark a clear path to find his way home. And he was no less determined to make his marriage work. No matter how he had arrived at it, or how long it had taken him to get there, he felt as if his identity was as bound up now in the success of his little family as his father’s had been in his family of ten. He and Barbara had loved each other once—their little girl was the tangible expression of that love—and now, almost as if he could will it, they would love each other again.

The Soul Stirrers’ single continued to sell, and Sam gladly lent his name to a concert promotion in Atlanta on December 6 (“Star vocalist Sam Cooke” would serve as “honored guest, MC,” the

Daily World

announced, “pay[ing] special tribute to his old group”). When he joined them onstage, the crowd went wild, and it was just like the old days, only more so. With their prospects looking up, the fellows all welcomed his participation, even Paul and Farley, who had been resistant for so long, and he appeared on several more programs over the next week or two, careful not to steal too much of the glory but pleased nonetheless to be back on the gospel road.

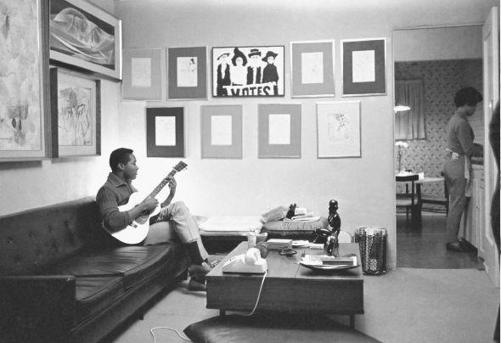

He had carved out Christmas to be at home with his wife and daughter. Jess and his wife, Bonnie, had been helping Barbara to decorate the apartment. The first time Sam brought Barbara out to their house on Stuart Lane, Jess said, “he saw these lamps we had, they were about five feet tall, shaped like vases, and he fell in love with them. Bonnie said, ‘Well, I know someone down at the Furniture Mart who can get them for you at cost.’ Sam said, ‘Could you do that for me?’ So they ended up with lamps like we had.” Barbara purchased couches like the Rands’, too, and Sam had always loved the way Jess and Bonnie had one wall covered with nothing but paintings, so Jess gave him a Frank Interlandi work called

Suffragettes,

a bold posterlike composition combining whimsy and determination in its portrayal of the extravagantly behatted women marchers. He and Bonnie had a couple of paintings by Z. Charlotte Sherman, whose work appealed to Sam for its “illusionary [effect] because as you look at it, you realize there’s more than one painting in the picture.” So Sam went out and bought one of her pictures, too. “He really loved the intrigue about it,” said Jess, who imagined it appealed to the secretive part of Sam’s nature.

It was a beautiful apartment, as nice, Barbara thought, as any place she had ever lived, with a kitchen/dinette, a patio, a formal living room for the pictures, a den that functioned as a dining room, and a guest room in addition to their own two bedrooms. Barbara put a plastic pool in the backyard for Linda to splash around in. The park was handy, and Sam gave her a cute little black-and-white Nash Rambler to drive around town, while he mostly drove his new white Corvette. It seemed like she had everything she had ever wanted—except for Sam.

She had thought this time it was going to be different, but even when he was at home, it seemed like he was there for Linda, he was there for his books, his paintings, his

things

—but not for her. She thought she knew what it was: for all of her efforts, she still wasn’t anywhere near the center of his world. So she resolved to make it even more of her business to learn his business, to be in a position to offer advice whenever it was called for—but she still felt an absence of any real intimacy, and it hurt.

L.C. came out for a visit and at Sam’s invitation took a suite at the Knickerbocker, driving Barbara’s little car all over town. Sam’s oldest sister, Mary, always a formidable presence and even more so now to Barbara because of her role in Barbara’s escape from Chicago, came out at Sam’s expense with her children, Gwendolyn and Don. She stayed with them for a week, and they all went to Disneyland together. For Linda, who was already an avid reader like her father, it was a little bit like discovering that she really was the fairy-tale princess after all. When her daddy was home, every day was like Christmas. “My most vivid memories are of him planning what we were going to do. He was always talking to me about his plans.” He read to her at night (“He was a wonderful reader”), and, of course, he was always drawing pictures for her—but he talked to her about his expectations, too. “My father was very strict about what he believed. He wanted me to go to college and learn the wider aspects of life. He had a certain way that he liked to see things done.” And, just as her grandfather Cook’s word was law in

his

home, that was the way their household was run.

On December 15, Sam got a draft of his RCA contract from the William Morris office, since by California law personal managers were not allowed to negotiate contracts. Jess made sure that William Morris wouldn’t collect any commission on the contract (“I told them, ‘I got him the deal, not you’”), and Sam in turn informed Jess that the agency was no more his manager’s friend than Sam’s. According to Sam, Larry Auerbach had asked him what he needed a manager for when William Morris could take care of all of his needs. Jess just shrugged it off; that was the way all agencies were—of course they’d like to eliminate the middle man. But he felt that he and Sam now had a special understanding. He had stood up for Sam, and he had delivered. And as he knew by now, that was Sam’s only measure.