Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (9 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

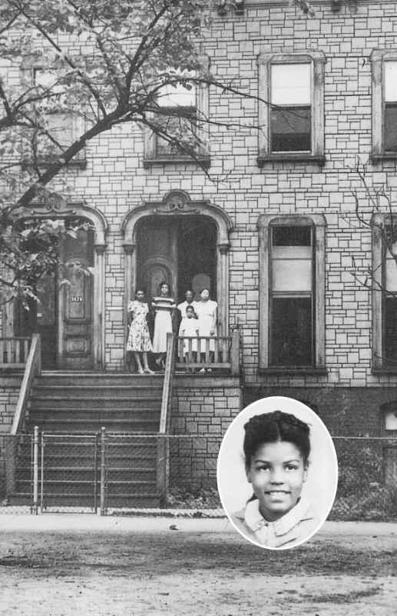

Sam had girls everywhere he went—in his friends’ and family’s observation, he had more trouble fighting them off than he did attracting them—but there was one girl in particular, Barbara Campbell, not quite thirteen and just finishing up eighth grade at Doolittle, to whom, to everyone’s astonishment, he seemed inextricably drawn. According to L.C.: “She was my girl first—when we were in grammar school—we wasn’t nothing but kids. But then she moved away.” She moved back because her mother had just gotten divorced and was about to marry her fourth husband, and her Grandmother Paige, her father’s mother, said enough was enough, she was going to keep these poor children together for a while. So they all moved into Grandmother Paige’s comfortable, two-story home at 3618 Ellis Park, Barbara and her twin sister, Beverly, and their older sister, Ella, and before long, she began meeting up with all her old friends from the neighborhood.

She ran into the Richards’ sister Mildred, whom she had originally met through QCs “announcer” Raymond Hoy when she was living with her other grandmother over on Rhodes. Mildred, whom everyone called “Mook,” told her about her brothers’ new singing group, and then a friend named Sonny Green reintroduced her to Sam standing in front of the chicken market, where Sam’s brother Willie worked.

3618 Ellis Park. Inset: Barbara Campbell, age eight.

Courtesy of Barbara Cooke and ABKCO

Sam said, “I know her!” And Sonny Green reacted with surprise. But she repeated her name, reminded Sam that she was one of the twins, and when he asked, “How old are you now?” at first she said, “Oh, I ain’t gonna tell you.” Then, when he pressed her, she told him fifteen, and when he challenged that, she compromised on fourteen. Sonny raised an eyebrow, but he didn’t say anything, and she told him afterward, with that peculiar mix of flirtation and intimidation that always seemed to fascinate men, “You better not tell on me—’cause I really like that guy.” She knew she loved him from the moment that they first met.

Mildred was the one who helped facilitate the first stumbling steps of their love affair. Barbara would meet Sam over at the Richards’ house—they would sit out in the hall and smooch once they were able to get rid of Mook’s brother Curtis. Then Barbara started going to church at Highway Baptist, where Mildred led the children’s choir. Her grandmother encouraged the friendship because the Richards were preacher’s kids, and Barbara started sleeping over at their house on Saturday night and walking to church with Sam on Sunday, stealing kisses along the way. Even though she had other “boyfriends,” she had never really cared about anybody before. But they didn’t do anything else, because there was nowhere else to do it. Soon Sam started coming around every day, and Mildred helped Barbara sneak out of the house a few times at night, telling her grandmother that she needed to speak with her, giving Sam and her a few minutes to smooch on a park bench. Barbara’s grandmother was very strict, so they had to be careful, but with Mildred’s help they were able to carry on their “play” affair right under her nose, and before long, Barbara’s older sister, Ella, joined them at church when she started going out with Mildred’s brother Jake.

Anyone looking at them from the outside might have thought that Barbara was being ensnared by this sophisticated “older man,” but to Barbara it was a case of the hunter being captured by the game. She loved Sam, she thought he was so cute with his marcelled hair and pug nose, and she knew he liked it when she told him so. She didn’t like it at all herself when he would tease her about her height or the fact that she had no breasts—but she could tell by his impish smile that he didn’t really mean it, and anyway, they would grow. And, of course, he never stopped coming around. She knew he had lots of other girls at his beck and call, but with her determination, Barbara felt, for all of his supposed sophistication, he didn’t stand a chance.

S

AM GRADUATED FROM WENDELL PHILLIPS

in June of 1948. He was clearly a young man with a future but not necessarily a future that anyone around him could clearly discern. He had announced his intentions to friends and family: he was not simply going to sing for a living, he was going to be a star. But how exactly he was going to achieve that stardom, whether gospel music would be the vehicle, the QCs the engine of his success, not even he could have said for certain, even though no one who knew Sam Cook could imagine him singing anything but spiritual music.

He was, in a sense, what they all wanted him to be, providing girlfriends and friends, casual acquaintances, mentors, and fans with the sense that they were “the one,” that however little time he might have available for them, all of his attention, all of his intellect, emotion, and charm were theirs for that moment. That was undoubtedly the key to his remarkable ability, both onstage and off, to communicate a message as sincere as it was convincing. And yet at some point inevitably he disappeared, he would vanish into a world of his own—whether the unexplored vistas that reading revealed to him, the vast territory of his unrealized ambitions, or a vision of the future that none of them was vouchsafed. For the most part he did it with a grace that minimized resentment, and few doubted that he would get where he was going—but they all felt his absence at one point or another, the elusiveness, the gulf between his apprehension of the world and their own.

That summer, with everyone out of school, the group really started to travel—on programs with the Flying Clouds, the Meditations, the CBS Trumpeteers, and the Fairfield Four. With R.B.’s encouragement, there was more and more talk about making a record. The Soul Stirrers recorded for Aladdin in Los Angeles, and R.B. was always telling them that he was going to set them up with this guy or that guy, but nothing ever came of it. On their brief tour with the Trumpeteers, they cut some dubs one afternoon in a church auditorium in Detroit, but no one knew what to do with the acetates, Cope had no earthly idea, and they just played them once in a while for themselves.

Cope was becoming more and more of an embarrassment, not just to the group but even to his own son. “My dad was the kind of person that Saturday nights he would go out and do a little too much. And Sundays we’d have a program, and he just couldn’t make it. So we had to do them by ourselves. That began to happen with more and more frequency, so after a while, we were just sort of out there.” He was hard on Bubba, too, forbidding him to travel to any of the weekday programs that would interfere with his education and refusing to even entertain the idea of his son quitting school like some of the rest of them were now talking about doing.

Charles saw them during this time when he was on leave, and he couldn’t believe what he was hearing. “They was singing down on Thirty-first and Cottage, and Sam said, ‘I want you to come hear us.’ I walked in, and it was just so amazing; Sam was singing ‘Swing Down, Chariot, Let Me Ride,’ and there was something that went through me. I said, ‘Man, this boy can sing!’”

Even so, change was inevitable. Cope just wasn’t carrying himself right, and Jake and Lee’s little brother, Curtis, was becoming increasingly undependable, failing to appear at rehearsals and showing less and less interest in the quartet’s fortunes. Not only that: Bubba would soon be going back to school, and that would be the end of touring for a while.

That was how Marvin and Gus came into the quartet.

Marvin Jones and Gus Treadwell had first encountered the QCs at their Mother’s Day program. They were both singing with the Gay Singers, an outgrowth of the widespread popularity of the piano-playing Gay Sisters (Evelyn, Mildred, and seventeen-year-old Geraldine), who had sponsored the all-star musicale at Holiness Community Temple in May. Marvin, a small, feisty youth of fifteen, sang lead baritone with the group; Gus, more stolid both in appearance and temperament, sang tenor; and the two Farmer sisters, Doris and Shirley, filled out the group.

Marvin had been singing all of his life. “At five I used to sing this song, ‘Pennies From Heaven,’ on the stage of the Avenue Theater on Thirty-first and Indiana—I had this little umbrella, and at the end of my song, I would open my umbrella up and the people would be throwing pennies onstage.” His uncle, Eugene Smith, was the new manager and dramatic baritone voice with the Roberta Martin Singers, whose classic “gospel blues” composition, “I Know the Lord Will Make a Way, Oh Yes, He Will,” had been particularly influential in the new movement. Marvin idolized his uncle. “I wanted to be just like him.” And, he was pleased to be able to say, “God gave me the gift to do so.”

Marvin and Gus had been partners from childhood on. They were like “two peas in a pod,” with their talent for singing and their passion for gospel music. But neither of them had ever encountered the QCs before, even though Marvin had been baptized by the Reverend Richard at Highway Missionary Baptist and Gus’ father had known Reverend Cook down South.

From the moment that Marvin heard the QCs sing their first notes, “I vowed that I would not die before I got in that quartet. I had to get in that quartet! Now, they didn’t need me. I was a baritone singer, and they

had

a baritone singer already. They were actually looking for a tenor singer, ’cause Curtis Richard just wasn’t acting right—so they wanted Gus. But I just started showing up at their rehearsals, and I would grab Sam in the hallway and hit a song. ’Cause I knew if I had that song, Sam would hit it, too, and then Gus would join in, and the next thing you knew, we were singing.”

Marvin was convinced that, if it came down to a choice between him and Bubba, he would prevail. “The difference between Bubba’s voice and mine was obvious. Bubba had a very light baritone, which did not give the Highway QCs the depth that they wanted, because with a deeper baritone, you sound more like men, more like adults. That’s what they were looking for.”

That may very well have been so, but in the end, it was Creadell’s school situation that gave Marvin the break he was looking for. “It went on for maybe two or three months, and then Bubba couldn’t make the program one day, for whatever reason, and we were standing on the corner, talking about the program, and Cope was telling the guys to get their white shirts and things and get them on ’cause they had to go make this church. Anyway, I said, ‘You want me to go, too?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, you can go, too.’ That’s how I got in the group. I had stopped going to school, and Bubba was still in school. From that point on, I wasn’t worried about Bubba. He was worried about me.”

As Lee Richard saw it: “That’s when we became dangerous—with Gus and little Marvin.” When they had Bubba, too, they could field two baritone singers and two strong leads, just like the Soul Stirrers. And even without Creadell, in L.C.’s view, “they had a more stable background.” They just sounded more like a real professional group.

Marvin never looked back. As far as he was concerned, the QCs, not the Stirrers, were the number-one group in the city (“We never wanted to be like them; we wanted to be where they were”). And Sam was the number-one attraction. “He was one of the most outgoing individuals that you could ever meet. And everybody liked him. There was no conceitment at all. But he wasn’t the kind of guy that you could trick. He always knew how to work it. Even when we was kids, he knew whether we should do it this way or that, spend this or hold on to that—he just always had that kind of talent.

“We went to bed singing, and we got up singing. We couldn’t live without it. We’d get done rehearsing at Cope’s at Four-sixty-six East Thirty-fifth, across from Doolittle, and then we’d go over to my girlfriend Helen’s and eat and rehearse all over again. We were doing what we loved to do, and we did it everywhere, and everybody knew us.”

O

NE OF THE PEOPLE

who got to know them was Louis Tate. Tate was thirty-three and working in a Gary, Indiana, steel mill, with a wife and nine children to support. He had had an early encounter with the gospel business when as a teenager he did some local promotion for the Big Four, a Birmingham quartet, in the area around Covington, Louisiana, where he grew up, and he had been very much involved in the Gary gospel scene from the time of his arrival in that city some fifteen years earlier. He was unprepared, though, for the reaction he felt the first time he heard the Highway QCs. “I just sat there, and I was spellbound,” he told writer David Tenenbaum, “’cause I didn’t know no kids could sing like that.”

As Marvin Jones remembered it, “He approached us at a church program, and he indicated that he had the resources that were necessary for the Highway QCs to make it and he wanted to be our manager. And at that time we were looking for a manager, because Cope—well, Cope drank quite a bit, and a lot of the programs, he didn’t go with us, because he was just always in his own world. So we moved on with Tate.”