Dreaming in Chinese (12 page)

Read Dreaming in Chinese Online

Authors: Deborah Fallows

Tags: #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Translating & Interpreting, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

One morning as the sun rose, I drew moral support from a friend visiting from New York, and together we gingerly approached them. They figured out our intentions right away. A very tiny woman beckoned us over with a little downward wave of her palm, and that was the beginning of my long relationship. I realized my only mistake had been waiting so long to make an approach. For the next five months, until hard winter set in, my new friends tucked me into their ranks, making sure I was always in eyeshot of someone to follow, and they gently bossed me around, all in the name of improvement.

Our tai chi corner of the park was not a street but served as a thoroughfare of sorts for morning commuters. Bicycles regularly threaded through our lines, often between our “high pat the horse” move and “kick to the left.” An occasional motor scooter did the same, its driver revving the limp little motor and leaning on the piercing horn. A certain salaryman in his dark blue pants and white shirt, carrying his worn briefcase, marched through our ranks every day as he headed for work. He walked facing backward, and at a brisk pace. No one batted an eye at his backward gait, as though it was the most natural thing in the world. I hid my astonishment, both at him and at the absence of interest from anyone else in my group.

For me, this was the moment I started to realize there is a gap between my Western perspective toward the physical world—order, place, direction, and even time—and that of the Chinese.

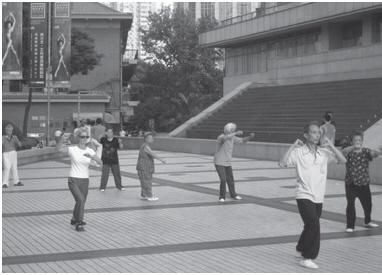

Early-morning tai chi in Shanghai’s People’s Park

Take reading and writing, for example. If you ask a Westerner about reading, you’re likely to get a rigid sense of direction and order: left to right, top row to bottom, just like you are reading right now. Chinese orientation is less predictable. Traditionally, Chinese was read in vertical columns, from top to bottom, and from right to left.

Familiarity with Western languages and modern technologies changed that, and the Chinese now generally read like we do. Chinese newspapers switched from vertical columns to horizontal rows in the mid-1950s.

Sometimes shape still dictates direction: Chinese characters on vertical banners are written top to bottom. Inscriptions over old temple gates are read right to left. Oddly, some tour buses have text written from the front to the rear along each side of the bus, that is from right to left on the right side of the bus and from left to right on the left side. Business cards are written however the owner designs them.

There is more. Our Western presentation of a word is as a group of letters bound together and marked off from other words by the physical space around them. But Chinese words written in characters are not bound by space. Each character, even if it is half of a two-character word, is separated equally from its neighbor. There is no telling where a word begins and ends—itwouldbeasifyouwere-readingthetextthisway.

The tradition of classical Chinese went a step further back: there was not even punctuation to mark sentences. Today, when the Chinese write out English translations, close enough is often good enough: the local fast-food shop in our Beijing neighborhood was called “Bee Fnoodles.”

Beyond text, the Chinese sense of position and place out in the real world differs from ours, too. There are a number of quaint tidbits, all reflected in the language. For example, my language teachers all taught us to think of Chinese as moving the focus from big to small: addresses telescope in from country, to city, to street, to number, to apartment. Personal names are ordered to start big with the family name and end small with the personal name. Dates are referenced from year to month to day.

When it comes to finding your bearings in China, east–west is the predominant axis, not our familiar north–south. You start with the east or west: In Shanghai, we lived near the westnorth, or

xīběi

,

section of People’s Park. We would sometimes fly on Northwest Airlines, or

Xīběi

, Westnorth in Chinese. Southeast Asia is

Dōngnán

, or Eastsouth Asia in Chinese. Manchuria is

Dōngběi

, or Eastnorth in China.

This concept is easy to grasp, but putting it into practice is harder than you’d guess. Even after years, this pattern does not come naturally to me. In Beijing, we lived at the intersection of two major roads. I directed taxis so often to the

dōngnán jiǎo

, or eastsouth corner of our intersection, that it rolled off my tongue. But in almost any other circumstance, I was like a grade school kid counting up sums on my fingers: I had to calculate my bearings step by step, first the actual geography, then the English words, then the reverse translation.

Beyond linguistic eccentricities, I find the ultimately curious—and confusing—reference point in the Chinese sense of world order is the conflation of two concepts, place and time, into a pair of antonyms:

xià

and

shàng

.

In Mandarin,

shàng is a common word whose meaning extends to a lot of different words in English: “up,” “on top,” “above,” “on.”

is a common word whose meaning extends to a lot of different words in English: “up,” “on top,” “above,” “on.”

Xià is its antonym, the word for “down,” “under,” “below,” “beneath,” “off.”

is its antonym, the word for “down,” “under,” “below,” “beneath,” “off.”

Shànghǎi

=

above the sea

Wǒ shàng lóu

=

I go upstairs

Lóu shàng

=

upstairs

Zài lù shàng

=

on the street

Shàng fēijī

=

get on the plane

Shān shàng

=

on the top of the mountain

Xiàmén

(a pretty coastal city south of Shanghai) = below + gate =

below the gate

Wǒ xià lóu

=

I go downstairs

Lóu xià =

downstairs

Zài zhuōzi xià

=

under the table

Xià chē

=

get off the train (car)

Shān xià

=

at the foot of the mountain

Simple enough. But Chinese also uses the same pair of words,

xià

and

shàng

, to refer to time.

Shàng refers to the past, as in last or previous;

refers to the past, as in last or previous;

xià refers to the future, as in next.

refers to the future, as in next.

Shàng Xīngqī èr

=

last Tuesday

Shàng ge yuè

=

last month

Xià ge yuè

=

next month

Xià cì

=

next time

My language teacher introduced both these concepts of place and time in the same lesson. Maybe it made sense to her that we should just cover all the meanings of

shàng

and

xià

at once, but it was hopelessly confusing to us.

To sort it out, I tried drawing diagrams with arrows of

shàng

pointing up for place and back for time, with

xià

pointing down for direction and forward for time. Other struggling fellow students invented their own clues to remember this (to us) arbitrary system. Our teacher seemed surprised that we had so much trouble, baffled that we didn’t find it normal that place and time were melded into a single word, which was the way her world worked.

On my daily forays, I ran into many practical examples of geographic dissonance with China. Deep in the bowels of the subway systems, I often joined a small crowd of riders— foreigners, but often Chinese, too—gathered around the station maps, studying to get our bearings on the world aboveground and to choose the best exit. We scratched our collective heads in confusion over the maps. Sometimes south is at the top of the map, sometimes north. Sometimes there are two maps side by side, but oriented upside down from each other. Occasionally, there is a third kind of map, drawn from the real-time perspective of the person viewing it, like the diagrams tacked to the inside of hotel room doors that direct you to the nearest exit.

The maps I consider upside down are no accident or mistake by Chinese standards. The proud litany of “The Four Great Inventions of China” includes the compass, along with paper, printing and gunpowder. Here is the orientation of an early Chinese compass: