Dress Like a Man (15 page)

Authors: Antonio Centeno,Geoffrey Cubbage,Anthony Tan,Ted Slampyak

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Beauty; Grooming; & Style, #Men's Grooming & Style, #Style & Clothing, #Beauty & Fashion

In previous chapters we've talked about broad concepts that apply to many different kinds of menswear: color, pattern, interchangeability, and so forth.

Now it's time to get down into the nitty-gritty.

What makes a suit a suit? And why is it the enduring icon of a well-dressed man?

Here's where you find out.

The Modern Suit

As far as fashions go, what we think of as a conventional, contemporary men's suit in the early 21st century is an impressively enduring style.

The basics started to evolve around the end of the 19th century, and the style as a whole hasn't changed much in its core principles since the 1920s and 1930s.

Variations have come in and out of style, of course, and there will always be new and aggressive re-interpretations, but the men's suit has followed a familiar pattern for the better part of a century now:

- a matched trouser/jacket pairing cut from the same cloth

- a V-shaped front opening

- a turned-down collar

- folded lapels stitched to the collar

- a working, buttoning front (no zippers or pullover-style tops)

- anywhere from zero to two vents (vertical slits running up from the bottom hem in the back)

That basic formula has had an impressively long run, and it shows no sign of being replaced any time soon.

What

does

change -- to some degree -- are the details of the cut and style, and that's where a man has an opportunity to express his individuality if he wants to. Suits can also be fitted in different ways, some of them more flattering than others, and it pays to know what you should ask of your tailor.

A Suit's Fit

More important than any other style consideration, you want a suit to sit as flatteringly as possible on your body.

Described below is the "perfect" suit fit. This is an ideal that's tough to reach without custom-tailoring, but you can get surprisingly close with careful shopping and some inexpensive adjustments to an off-the-rack suit. The key is to buy a suit that already comes as close as possible to the following fits:

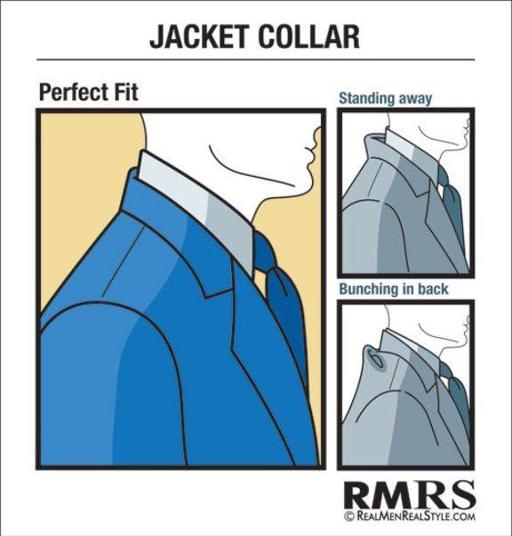

- The collar

should touch your shirt collar all the way around your neck. There should be no gap between the two. If the jacket collar stands off from the shirt collar, the neck opening is too large.

- The shoulders

of a suit jacket are very difficult to adjust. Never buy a suit whose jacket sits badly on your shoulders! The seam where the shoulder meets the sleeve should sit at the very end of your shoulder -- not partway down the bicep, and not partway toward the neck.

- The armscye

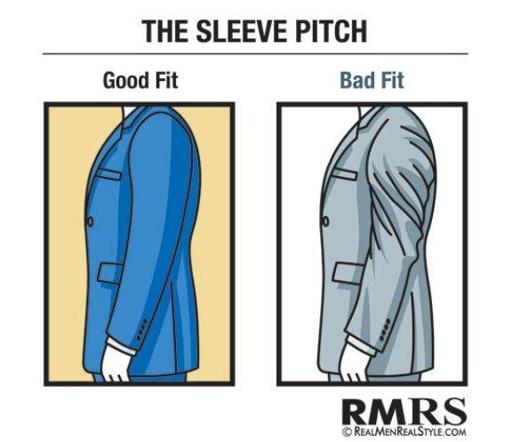

-- the hole where the sleeves meet the torso -- is more important than most men give it credit for. If it's too tight, the seam will dig up into the armpit. If it's too loose, the armpits will sag, pulling the side of the suit out from the body. Like the shoulders, this is a tough one to adjust, so save yourself trouble and never buy a jacket that isn't a close (but not overtight) fit at the armscye. - The arm pitch

is the angle of the sleeve where it joins the jacket. You want a pitch that's as close to your natural posture as possible. Some men angle their shoulders further forward than others. If the bend of your body doesn't come fairly close to matching the bend of your jacket, you'll get tugging and twisting on the sleeve, which will create wrinkles and pinch your body.

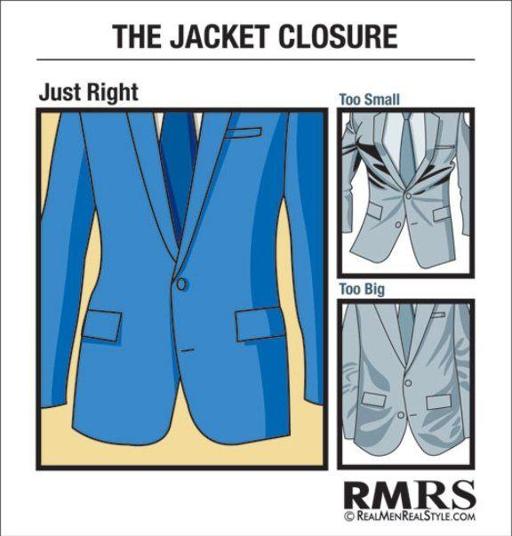

- The chest

should sit close enough that the lapels don't sag or bend away from your body. - The waist

should button without straining. When fastened, there should be no wrinkles or folds in the fabric around the button. It should hang flat against the front of your shirt, without sagging.

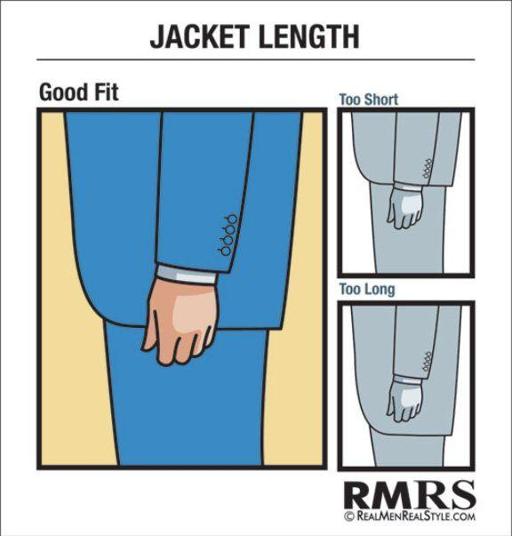

- The length

should end right around the curve of the buttocks, at or just below their widest point. Too far beyond that and the jacket starts to look like an overcoat; too far above it and the back hem with flip outward like a duck tail.

- The sleeves

should stop at or just above the large bone at the base of your thumb, where the wrist and the hand come together. It should be slightly shorter than your dress shirt sleeves -- "a half inch of linen" is the old-fashioned phrase, and it still holds basically true. The jacket sleeve should never fully hide the shirt cuffs.

Obviously, very few off the rack suits are going to be a perfect fit in every one of these locations.

The most important (when purchasing off the rack) are the shoulders, armsye, and arm pitch -- those are both challenging and expensive to fix, with no guarantee of good results.

The length of the sleeves and the bottom of the jacket, as well as the fit at the waist, are easier to adjust. Err on the side of too long or too loose, rather than too short and too tight, and your tailor should have enough cloth to work with.

Collar and chest fall somewhere in between. They're somewhat difficult to adjust, but a touch of looseness there isn't the deal-breaker that it can be elsewhere. Try for the best fit you can, but focus on the shoulders and arms. Without a good fit there, the jacket is never going to sit right on your body.

Suit Styles

The

fit

refers to the specific measurements of the suit at various points. It's important to get a good fit, tailored to your body, no matter what kind of suit you're wearing.

Styles of suit, on the other hand, are usually broken down by the type of jacket used. There are three basic models in common use today:

- Single-breasted suits

have sides that do not overlap when fastened. They are buttoned in the middle of the torso, usually with a single button (on a two-button jacket) or with two buttons (on a three-button jacket). The lowest button is almost always left unfastened. - Three-piece suits

are just a single-breasted suit with an added waistcoat (vest) made from the same fabric as the jacket and trousers. They are a little more elegant-looking, but also a touch more old-fashioned, and of course more expensive. - Double-breasted suits

have two sides that overlap when buttoned, usually with two columns of buttons. They are generally considered more formal than single-breasted suits, and should be worn buttoned at all times.

Within those three broad category is the potential for quite a bit of variety. An aggressively modern single-breasted suit might only have a single button and buttonhole, slung low on the torso, while a more staid version might have three buttons, with two fastening to close the jacket about halfway up the chest.

Double-breasted suits in particular come in a number of different "button stances," to accommodate differently-sized torsos. They are generally described using a "number-on-number" phrase, listing first the number of buttons total and then the number that actually fasten: a "six-on-two" jacket has two columns of three buttons each, but only the lower two buttons on the wearer's right side actually fasten through buttonholes.