Drood (111 page)

Of course he will come. Beard always has come.

And he will come quickly. His house is only just across the street. But he will not come in time.

I will be in my big armchair, just as I am now. There will be a pillow behind my head, just as there is now.

The fire will still be burning behind the grate.

I will not be able to feel its heat.

And I apologise for these blobs. The sleeve of my dressing gown truly is too large.

Sunlight will be coming in the high window, just as it is now, and only a little higher, just as the coal in the fireplace will be burned only a little lower. It will be sometime after 10 AM. And despite the sunlight, the room will be growing darker by the minute.

I will not be alone.

You always knew, Reader, that I would not be alone at the end.

Several figures will be in the room with me and gliding closer as—perhaps—I still strive to write, but my hand will be nerveless, my writing finished forever, and the pen will achieve only vague scratches and blobs.

Drood will be here of course. His tongue will flick in and out. He will ssso want to ssshare a ssecret with Mr Collinssss.

Behind and to Drood’s left, I think, I will see Barris, Inspector Field’s son. Field will be there also, behind his son. They both will show cannibals’ teeth. To Drood’s right will stand Dickenson, not the adopted son of Dickens after all. He is and always will be Drood’s creature. And behind these will be more shapes. All will be in black suits and capes. They will look silly here in the fading sunlight.

I will not be able to clearly make out their faces. The scarab will, at long last, have eaten through my eyes.

But there will be a huge, indistinct blur of a man near the back. It could be Detective Hatchery. I will just barely be able to make out a terrible concavity beneath the black waistcoat and funeral suit, like some sort of nightmare negative pregnancy.

But, Reader (I have spied you out—I know you care more about this than about me), Dickens will not be there among them.

Dickens is not there.

But I believe that I will be. I am already.

Then I will hear dear Beard’s footsteps on the stairs, but suddenly the figures in my bedroom will all begin crowding closer and speaking at once, hissing and slurring and rasping and spitting sounds as they press upon me, all speaking and gibbering at once. I would lift both hands over my ears, if I were able to. I would close what is left of my eyes, if I were able to. For the faces will be terrible. And the din will be intolerable. And it will be very painful in a way I have never known.

Forty-five minutes remain before all this comes to pass—before I send the note to Frank Beard and the Others arrive before he does—but already it is painful and terrible and intolerable and unintelligible.

Unintelligible.

The author wishes to acknowledge the help and editing excellence of Reagan Arthur, executive editor at Little, Brown, as well as the truly extraordinary work of senior copyeditor Betsy Uhrig. I’m sure there still will be infelicities and errors in this novel, but in almost all cases, the fault will have been mine. (If stubbornness were a virtue, I’d have one foot in Heaven.)

Only a partial list of the biographical and other sources related to Charles Dickens and his era which I consulted is possible here, but the author would especially like to acknowledge the following—

Dickens

by Peter Ackroyd, © 1990, pub. by HarperCollins;

Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumphs

by Edgar Johnson, © 1952, pub. by Simon and Schuster;

Dickens: A Biography

by Fred Kaplan, © 1988, pub. by The Johns Hopkins University Press;

Charles Dickens As I Knew Him: The Story of the Reading Tours in Great Britain and America (

1866

–

1870

)

by George Dolby, © 1887, pub. in Popular Edition by T. Fisher Unwin, London;

Charles Dickens

by Jane Smiley, © 2002, pub. by Penguin Putnam Inc.;

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens

edited by John O. Jordan, © 2001, pub. by Cambridge University Press;

Life of Charles Dickens

by John Forster, © 1874;

The Mystery of Edwin Drood

by Charles Dickens, © 1870 by

Household Words,

Oxford University Press Edition © 1956.

Some other sources for Dickens and his era which the author would like to acknowledge include—

Dickens and His Family

by W. H. Bowen, © 1956;

The Life of Charles Dickens as Revealed in His Writing

by Percy Fitzgerald, © 1905;

The Changing World of Charles Dickens

edited by R. Giddings, © 1983;

Victorian People and Ideas

by Richard D. Altick, © 1973;

The World of Charles Dickens (A Pitkin Guide)

by Michael St. John Parker, © 2005;

Subterranean Cities: The World Beneath Paris and London,

1800

–

1945 by David L. Pike, © 2005;

Dickens and Daughter

by Gladys Storey, © 1939;

Dickens, Reade, and Collins: Sensation Novelists

by W. C. Phillips, © 1919;

London

1808

–

1870

: The Infernal Wen

by Francis Sheppard, © 1971;

Charles Dickens, Resurrectionist

by Andrew Sanders, © 1982;

The Speeches of Charles Dickens

edited by K. J. Fielding, © 1950;

The Actor in Dickens

by J. B. van Amerongen, © 1926;

Opium and the Romantic Imagination

by Alethea Hayter, © 1968;

Dickens and Mesmerism: The Hidden Springs of Fiction

by Fred Kaplan, © 1988;

The Shakespeare Riots: Revenge, Drama, and Death in Nineteenth-Century America

by Nigel Cliff, © 2007.

Internet sources relating to Dickens and his world are too numerous to list in full, but a few that the author especially wishes to acknowledge are—

“Inspector Charles Frederick Field” at

www.ric.edu/rpotter/chasfield.html

; “Victorian London—District—Streets—Bluegate Fields” at

www.victorianlondon.org/districts/bluegate.html

; “Dickens’ London” at

www.fidnest.com

/~dap.1955/dickens/dickens_ london_map.html; “Reprinted Pieces by Charles Dickens” at

www.classicbookshelf.com/library/charles_dickens/reprinted_pieces/19/html

; “Housing and Health (Deaths from cholera in Broad Street, Golden Square, London, and the neighbourhood, 19 August to 30 September, 1854)” at

www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~city19/viccity/househealth.html

; “Beetles as Religious Symbols, Cultural Entomology, Digest 2” at

www.insectos.org/ced2beetles_rel_sym.html

; “Modern Egyptian Ritual Magick: Ceremony of Blessing and Naming a New Child” at

www.idolhands.com/egypt/netra/naming.html

.

For insight into Charles Dickens’s

Bleak House

, the author wishes to acknowledge the amazing lecture on that novel given at Wellesley College by Vladimir Nabokov (even though Nabokov led the author astray on one central word in a powerful quotation, an error completely missed by the author—who’d just finished rereading

Bleak House

—but caught by the inimitable copyeditor Betsy Uhrig). That lecture is collected in

Lectures on Literature

edited by Fredson Bowers, © 1980, pub. by Harcourt, Inc.

The author wishes to acknowledge the following sources in his research on Wilkie Collins—

The Secret Life of Wilkie Collins

by William Clarke, © 1988, pub. by Sutton Publishing Limited;

The Public Face of Wilkie Collins: The Collected Letters, Volumes I–IV

edited by William Baker, Andrew Gasson, Graham Law, Paul Lewis, © 2005, pub. by Pickering & Chatto;

The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins

by Catherine Peters, © 1991, pub. by Martin Secker & Warburg;

Wilkie Collins: A Biography

by Kenneth Robinson, © 1952, pub. by the MacMillan Company;

Some Recollections of Yesterday

by Nathaniel Beard, © 1894, pub. in

Temple Bar, Vol. CII; Memories of Half a Century

by R. C. Lehmann, © 1908, pub. by Smith Elder;

The Moonstone

by Wilkie Collins, first published in

Temple Bar

© 1874, Hesperus Classics edition pub. by Hesperus Press Limited.

For those interested in Wilkie Collins, the author recommends one especially helpful Web site—“Wilkie Collins Chronology” at

www.-wilkie-collins.info/wilkie_collins_chronology.html

.

Finally, and always, my deepest thanks and dearest love to my first reader, primary proofreader, and ultimate source of inspiration—Karen Simmons.

D

AN

S

IMMONS

is the award-winning author of several novels, including the

New York Times

bestsellers

Olympos

and

The Terror

. He lives in Colorado.

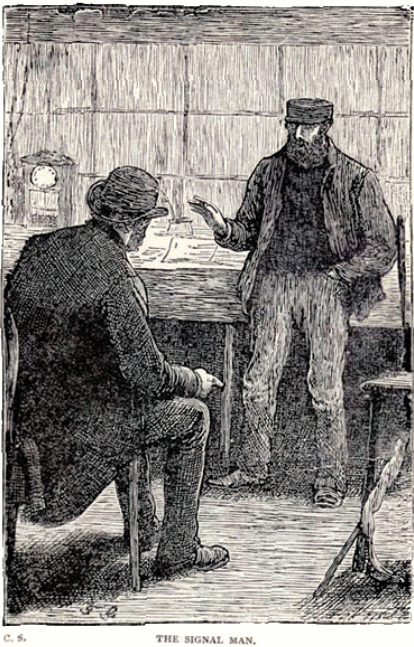

The Signal-Man

by

Charles Dickens

“Halloa! Below there!”

When he heard a voice thus calling to him, he was standing at the door of his box, with a flag in his hand, furled round its

short pole. One would have thought, considering the nature of the ground, that he could not have doubted from what quarter

the voice came; but instead of looking up to where I stood on the top of the steep cutting nearly over his head, he turned

himself about, and looked down the Line. There was something remarkable in his manner of doing so, though I could not have

said for my life what. But I know it was remarkable enough to attract my notice, even though his figure was foreshortened

and shadowed, down in the deep trench, and mine was high above him, so steeped in the glow of an angry sunset, that I had

shaded my eyes with my hand before I saw him at all.

“Halloa! Below!”

From looking down the Line, he turned himself about again, and, raising his eyes, saw my figure high above him.

“Is there any path by which I can come down and speak to you?”

He looked up at me without replying, and I looked down at him without pressing him too soon with a repetition of my idle question.

Just then there came a vague vibration in the earth and air, quickly changing into a violent pulsation, and an oncoming rush

that caused me to start back, as though it had force to draw me down. When such vapour as rose to my height from this rapid

train had passed me, and was skimming away over the landscape, I looked down again, and saw him refurling the flag he had

shown while the train went by.

I repeated my inquiry. After a pause, during which he seemed to regard me with fixed attention, he motioned with his rolled-up

flag towards a point on my level, some two or three hundred yards distant. I called down to him, “All right!” and made for

that point. There, by dint of looking closely about me, I found a rough zigzag descending path notched out, which I followed.

The cutting was extremely deep, and unusually precipitate. It was made through a clammy stone, that became oozier and wetter

as I went down. For these reasons, I found the way long enough to give me time to recall a singular air of reluctance or compulsion

with which he had pointed out the path.

When I came down low enough upon the zigzag descent to see him again, I saw that he was standing between the rails on the

way by which the train had lately passed, in an attitude as if he were waiting for me to appear. He had his left hand at his

chin, and that left elbow rested on his right hand, crossed over his breast. His attitude was one of such expectation and

watchfulness that I stopped a moment, wondering at it.

I resumed my downward way, and stepping out upon the level of the railroad, and drawing nearer to him, saw that he was a dark

sallow man, with a dark beard and rather heavy eyebrows. His post was in as solitary and dismal a place as ever I saw. On

either side, a dripping-wet wall of jagged stone, excluding all view but a strip of sky; the perspective one way only a crooked

prolongation of this great dungeon; the shorter perspective in the other direction terminating in a gloomy red light, and

the gloomier entrance to a black tunnel, in whose massive architecture there was a barbarous, depressing, and forbidding air.

So little sunlight ever found its way to this spot, that it had an earthy, deadly smell; and so much cold wind rushed through

it, that it struck chill to me, as if I had left the natural world.

Before he stirred, I was near enough to him to have touched him. Not even then removing his eyes from mine, he stepped back

one step, and lifted his hand.

This was a lonesome post to occupy (I said), and it had riveted my attention when I looked down from up yonder. A visitor

was a rarity, I should suppose; not an unwelcome rarity, I hoped? In me, he merely saw a man who had been shut up within narrow

limits all his life, and who, being at last set free, had a newly-awakened interest in these great works. To such purpose

I spoke to him; but I am far from sure of the terms I used; for, besides that I am not happy in opening any conversation,

there was something in the man that daunted me.

He directed a most curious look towards the red light near the tunnel’s mouth, and looked all about it, as if something were

missing from it, and then looked it me.