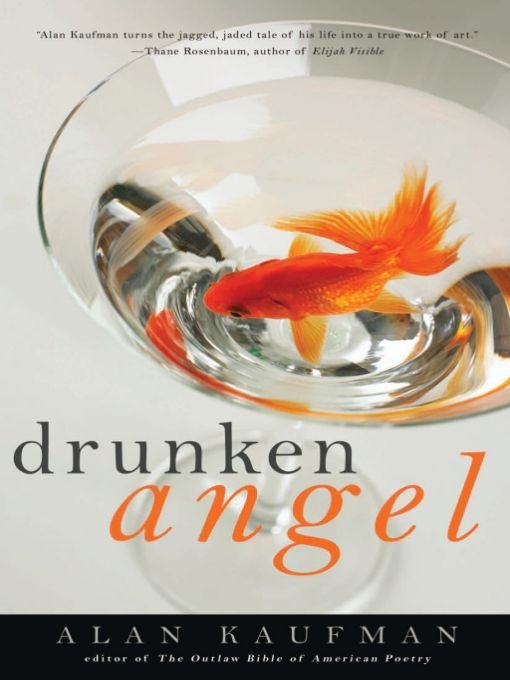

Drunken Angel (9781936740062)

Read Drunken Angel (9781936740062) Online

Authors: Alan Kaufman

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

It's very thrilling to see darkness again.

Â

Â

âDiane ArbusPART ONE

BOOK ONE

1ON A LAMP STAND BY HIS BED MY FATHER KEPT A small stack of

True Men's Adventures

and

Stag

, magazines with illustrated feature stories bearing titles like “Virgin Brides for Himmler's Nazi Torture Dungeons” and “Hitler's Secret Blood Cult” or “Death Orgy in the Rat Pits of the Gestapo.”

True Men's Adventures

and

Stag

, magazines with illustrated feature stories bearing titles like “Virgin Brides for Himmler's Nazi Torture Dungeons” and “Hitler's Secret Blood Cult” or “Death Orgy in the Rat Pits of the Gestapo.”

I couldn't tear my eyes away.

The covers showed buxom, naked young womenâJewish, I presumedâin shredded slips, their panting and perspiring busts crisscrossed with luscious-looking whip welts, hung by wrists from ceilings, about to be boiled, others spread-eagled on torture tables, dripping red cherry cough dropâcolored blood as shirtless bald grinning sadists manned obscene instruments.

Is this what my birth looked like? Had my mother, a French-born Jew, been a virgin torture bride for the pleasures of the medical Gestapo? And is that why she still constantly revisits doctors and goes to the hospital to have surgeries? To my libido, it was logical.

To her, my hungers were disgraceful. “You're hungry? You don't

know what hunger is,” she told me, mopping her flushed face with her apron, when I requested more bread.

know what hunger is,” she told me, mopping her flushed face with her apron, when I requested more bread.

I was too fat, she said. “Look at you! You should be ashamed! You have breasts like a woman. In the war I hid in basements and attics, starving, and all around me German soldiers with dogs. I was just a little older than you. Hungry! What do you know? Your waist is bigger than mine!”

But what about the Gestapo rat pits, I wondered, shutting my eyes, trying to imagine her hung over cauldrons, like the ones bubbling on the stove, or chained to a wall, naked and starving, a thin figure with voluptuous breasts, a moan parting her lips. Shifting uncomfortably in my seat, I grew hard under the dinette table.

The magazines' cheap black-and-white newsprint guts contained boner-inspiring photo art, grainy flicks of scantily clad women of ill repute, black bars printed over their eyes. You saw pretty clearly their cleavages, could form a mental movie. I knew that sex was bad things one did and I knew the mags were sinful, but reading was the only thing I seemed to excel in at school; I failed most subjects. I read the mags compulsively, desperately, yet with a curious mentholated sense of remove, the coolness of sin, the way others pray, for fantasy, escape from the circumstances of my life, for I did not yet understand about libraries, that you can be only eight years old but based on honor take home books, since there was no honor in my world where I was a groveling larva trying just not to get crushed.

Â

My father played cards and bet on horses. He brought home stolen hi-fi consoles and portable TVs, purchased hot, or hung out with his brother, Arnold, and the kids, who were mainly jailbirds and hoods. And if I could, I stole tooâyou couldn't trust a kid like me, for now and then I took change from his pockets, filched cupcakes and comics from the candy stores.

When an actual book fell into my hands, street-found, some yellowish crumbling paperback, Ted Mack's

The Man From O.R.G.Y.

, or George Orwell's

1984

, I handled these with proprietary reverence, inscribed the title page with “Property of Alan Kaufman” and a little poem plagiarized from Pop, who had it scrawled in the only two books he kept, a Webster's and this antho of best prose from Nat Fleisher's

Ring

Magazine:

The Man From O.R.G.Y.

, or George Orwell's

1984

, I handled these with proprietary reverence, inscribed the title page with “Property of Alan Kaufman” and a little poem plagiarized from Pop, who had it scrawled in the only two books he kept, a Webster's and this antho of best prose from Nat Fleisher's

Ring

Magazine:

“I pity the river, I pity the brook, I pity the one who steals this book.”

It seemed like great poetry to me. I wondered if he made it up, was some kind of poet. This, the first poem I ever learned, stolen from my dad, made me want to write others.

I tried. When I showed my efforts to my teacher, she put across the top: “Excellent! You're a real writer!” Even my mother encouraged this idea, and kept my poems stashed in her secret drawer of precious things, folded away among silken panties and brasâmy very first archive.

My poems, writing and reading, became erotically tinged, a way to earn love as I couldn't by other means. Writing seemed to befriend me. I felt less lonely, began to dream, and from the page a voice seemed to speak directly to me and to no one else.

Be a writer, it told me.

When I learned that even I could join the library and check out books six at a time, my mother said I would run up fines she couldn't pay, don't I know how poor we are, but I went anyway, returning home with arms full of new sentries to post around my bed. A kind of literary fortress stood guard over my hopes: Ernest Hemingway, James Jones, Leon Uris, Thomas Wolfe, Dylan Thomas, Irwin Shaw, a new bulwark against my mother, who entered my room raging and lashing at me with a belt for my defiance as I cringed in the corner crying and glanced at the books for

courage. Could sense Hemingway and Dylan Thomas there in the room, encouraging. Alone, vowed someday to join them. At night, with a flashlight under my blanket tent, I mouthed artful words I barely understood, until, now and then, narratives took form, more real than my reality, and obliterated the grimness of the day and loneliness of my night.

2courage. Could sense Hemingway and Dylan Thomas there in the room, encouraging. Alone, vowed someday to join them. At night, with a flashlight under my blanket tent, I mouthed artful words I barely understood, until, now and then, narratives took form, more real than my reality, and obliterated the grimness of the day and loneliness of my night.

DEVOURING STAG ZINES FELT DIFFERENT FROM struggling through Shaw's “The Girls in Their Summer Dresses” or Hemingway's “The Battler.” Books made me feel healthy and like a boy. Books fed my Angel. But the magazines bred a secret world of shame, a growing hint of uncontrolled chaos, a black drunkenness of the senses, and I plundered them with the rapt terror of forbidden realms I intuited a boy my age shouldn't be privy to.

This was a worldview of transgressive pornographic global evil I shared with my parents, a dark adult-only newsstand read on life, one with the sickening graininess of a Weegee

Daily News

photo that I felt myself too young to have, for at nine it crazed me to think that out there in the glass-strewn Bronx streets were devil worshippers, gangsters, Nazis, Commies, rapists, torturers, spree killersâscary men in sweat-drenched tees roaming with razor-buckled garrison belts wrapped around their fists, waiting to pounce on me. Yet knowing this made me feel closer to Mom and Dad, even as it gutted deep runnels in my soul,

hidden labyrinthine fear sewers that began to fester and stink.

Daily News

photo that I felt myself too young to have, for at nine it crazed me to think that out there in the glass-strewn Bronx streets were devil worshippers, gangsters, Nazis, Commies, rapists, torturers, spree killersâscary men in sweat-drenched tees roaming with razor-buckled garrison belts wrapped around their fists, waiting to pounce on me. Yet knowing this made me feel closer to Mom and Dad, even as it gutted deep runnels in my soul,

hidden labyrinthine fear sewers that began to fester and stink.

The mags were spellbindingly addictive. I could not just read one about statuesque blondes bound to altars for ritualized rape and torture and then put down the mag and go sing along with Howdy Doody. I would need to read until the stories ran out and then, jonesing like a junkie, wait until Pop brought some more home. But even the next hit of

Stag

was insufficient. Slowly, I descended into the bottomless pit.

Stag

was insufficient. Slowly, I descended into the bottomless pit.

Pop frequently replenished his stock but I was not allowed to read them until he'd been through them first. An illiterate with a fourth-grade education, it could take him days.

When home, Pop lay abed in his boxer shorts and white T-shirt, asleep and farting noxious fumes until nightfall, when he would rise and go to his job at the main post office on 33rd Street and Ninth Avenue in Manhattan, work a shift from midnight to 8:00 a.m., at which time he emerged, squinting, into the early morn and headed over to Times Square for a breakfast of burger patties and Orange Julius, and then a browse in the mag racks for the latest number of

True Men's Adventures

.

True Men's Adventures

.

When these arrived I planned my commando raid. Waited for my mother to bustle out with shopping cart, complaining about what a good-for-nothing he was, letting his poor wife go out in the rain; how he couldn't care less about her kidney stones or high blood pressure.

“Oh, yeah?” he'd yell back from his throne on the bed, half asleep, face crushed to a pillow. “And what the hell you think I been doing all night? Working to put food in your big goddamned insulting mouth!”

“Oh, to hell with you!” she called back and slammed out. While Howie lay in bed watching TV, I would gently nudge open my parents bedroom door with fingertips, peer in at my

father's calloused feet, listen for his sleep breathing and crawl in on my belly slowly, noiselessly. Slithered undetected, slid the new mags off the rack, and crawled out, booty in hand.

father's calloused feet, listen for his sleep breathing and crawl in on my belly slowly, noiselessly. Slithered undetected, slid the new mags off the rack, and crawled out, booty in hand.

Dad's gonna kill you, Howie would say. He didn't look at the mags, didn't dare. Lay on his bed reading comics, watching TV. A good boy.

We had twin beds, side by side. Lying on mine, I compulsively read them from cover to cover, all the way to the Frederick's of Hollywood ads. The horrifying stories, stimulating, strange, stirred vague longings, desires that I could not identify but felt increasingly frightened of and sickened by, though I couldn't stop, aware as I read of the stirring between my legs.

All this made me feel nightmarishly arrant in the watching invisible eyes of the world and of the writers I admired, as if Hemingway could see me from his throne in the sky library and shook his head in disappointed disgust.

Â

Yet, I did not know what sex was. My birds and bees were satanic torture rites and Goering's Pain Slaves.

I did not even know about coupling. Didn't exist. The stag mags only alluded indirectly to coitus, draping the act in coded euphemisms.

When kids made screwing jokes, I hadn't a clue what they were referring to, just couldn't guess. Babies came from torture chambers, where now and then my mother lay moaning and bloody on some hospital table, surrounded by Nazi surgeons, an incorrigible torture bride getting her insides scrubbed, stabbed, and stitched. In front of the TV, her eyes grew soft watching movie people kiss. “You should get yourself a nice girl someday,” she'd say, turning to me. “One with a lot of money.”

Other books

Day of Wrath by Jonathan Valin

Mountain of the Dead by Keith McCloskey

Dead Man's Hand by Luke Murphy

Dragon Master by Alan Carr

Stormsinger (Storms in Amethir Book 1) by Cain, Stephanie A.

FIVE-SECOND SEDUCTION by Myla Jackson

Christopher and His Kind by Christopher Isherwood

Perfect Lies by Kiersten White