Earth Hour

Authors: Ken MacLeod

The assassin slung the bag concealing his weapon over his shoulder and walked down the steps to the rickety wooden jetty. He waited as the Sydney Harbour ferry puttered into Neutral Bay, cast on and then cast off at the likewise tiny quay on the opposite bank, and crossed the hundred or so meters to Kurraba Point. He boarded, waved a hand gloved in artificial skin across the fare-taker, and settled on a bench near the prow, with the weapon in its blue nylon zipped bag balanced across his knees.

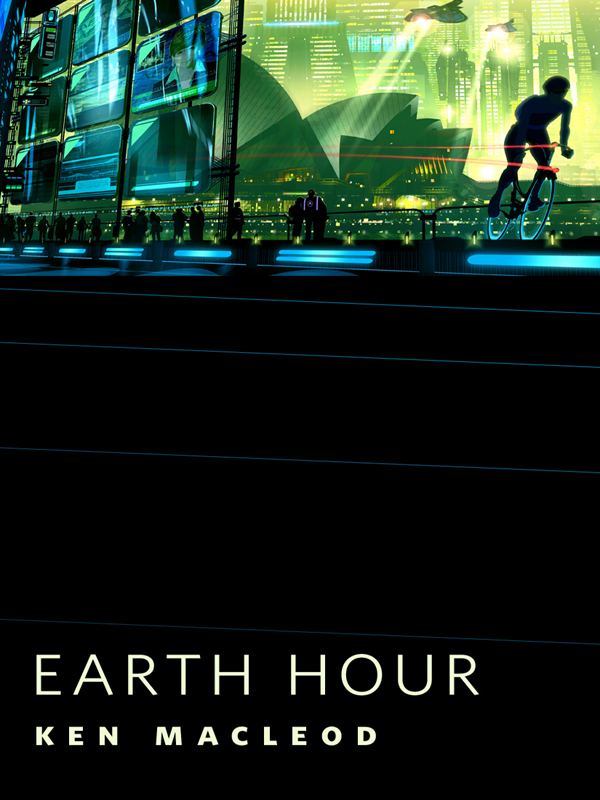

The sun was just above the horizon in the west, the sky clear but for the faint luminous haze of smart dust, each drifting particle of which could at any moment deflect a photon of sunlight and sparkle before the watching eye. A slow rain of shiny soot, removing carbon from the air and as it drifted down providing a massively redundant platform for observation and computation; a platform the assassin’s augmented eyes used to form an image of the city and its environs in his likewise augmented visual cortex. He turned the compound image over in his head, watching traffic flows and wind currents, the homeward surge of commuters and the flocking of fruit bats, the exchange of pheromones and cortext messages, the jiggle of stock prices and the tramp of a million feet, in one single godlike POV that saw it all six ways from Sunday and that too soon became intolerable, dizzying the unaugmented tracts of the assassin’s still mostly human brain.

One could get drunk on this. The assassin wrenched himself from the hubristic stochastic and focused, narrowing his attention until he found the digital spoor of the man he aimed to kill: a conference delegate pack, a train fare, a hotel tab, an airline booking for a seat that it was the assassin’s job to prevent being filled the day after the conference…The assassin had followed this trail already, an hour earlier, but it amused him to confirm it and to bring it up to date, with an overhead and a street-level view of the target’s unsuspecting stroll towards his hotel in Macleay Street.

It amused him, too, that the target was simultaneously keeping a low profile–no media appearances, backstage at the conference, a hotel room far less luxurious than he could afford, vulgar as all hell, tarted in synthetic mahogany and artificial marble and industrial sheet diamond–while styling himself at every opportunity with the obsolete title under which he was most widely known, as though he reveled in his contradictory notoriety as a fixer behind the scenes, famous for being unnoticed. “Valtos, first of the Reform Lords.” That was how the man loved to be known. The gewgaw he preened himself on. A bauble he’d earned by voting to abolish its very significance, yet still liked to play with, to turn over in his hands, to flash. What a shit, the assassin thought, what a prick! That wasn’t the reason for killing him, but it certainly made it easier to contemplate.

As the ferry visited its various stages the number of passengers increased. The assassin shifted the bag from across his knees and propped it in front of him, earning a nod and a grateful smile from the woman who sat down on the bench beside him. At Circular Quay he carried the bag off, and after clearing the pier he squatted and opened the bag. With a few quick movements he assembled the collapsible bicycle inside, folded and zipped the bag to stash size, and clipped the bag under the saddle.

Then he mounted the cycle and rode away to the left, around the harbor and up the long zigzag slope to Potts Point.

There was no reason for unease. Angus Cameron sat on a wicker chair on a hotel room balcony overlooking Sydney Harbour. On the small round table in front of him an Islay malt and a Havana panatela awaited his celebration. The air was warm, his clothing loose and fresh. Thousands of fruit bats labored across the dusk sky, from their daytime roost in the Botanic Gardens to their nighttime feeding grounds. From three stories below, the vehicle sounds and voices of the street carried no warnings.

Nothing was wrong, and yet something was wrong. Angus tipped back his chair and closed his eyes. He summoned headlines and charts. Local and global. Public and personal. Business and politics. The Warm War between the great power blocs, EU/Russia/PRC versus FUS/Japan/India/Brazil, going on as usual: diplomacy in Australasia, insurgency in Africa. Nothing to worry about there. Situation, as they say, nominal. Angus blinked away the images and shook his head. He stood up and stepped back into the room and paced around. He spread his fingers wide and waved his hands about, rotating his wrists as he did so. Nothing. Not a tickle.

Satisfied that the room was secure, he returned to his balcony seat. The time was fifteen minutes before eight. Angus toyed with his Zippo and the glass, and with the thought of lighting up, of taking a sip. He felt oddly as if that would be bad luck. It was a quite distinct feeling from the deeper unease, and easier to dismiss. Nevertheless, he waited. Ten minutes to go.

At eight minutes before eight his right ear started ringing. He flicked his earlobe.

“Yes?” he said.

His sister’s avatar appeared in the corner of his eye. Calling from Manchester, England, EU. Local time 07:52.

“Oh, hello, Catriona,” he said.

The avatar fleshed, morphing from a cartoon to a woman in her mid-thirties, a few years younger than him, sitting insubstantially across from him. His little sister, looking distracted. At least, he guessed she was. They hadn’t spoken for five months, but she didn’t normally make calls with her face unwashed and hair unkempt.

“Hi, Angus,” Catriona said. She frowned. “I know this is…maybe a bit paranoid…but is this call secure?”

“Totally,” said Angus.

Unlike Catriona, he had a firm technical grasp on the mechanism of cortical calls: the uniqueness of each brain’s encoding of sensory impulses adding a further layer of impenetrable encryption to the cryptographic algorithms routinely applied…A uniquely encoded thought struck him.

“Apart from someone lip-reading me, I guess.” He cupped his hand around his mouth. “OK?”

Catriona looked more irritated than reassured by this demonstrative caution.

“OK,” she said. She took a deep breath. “I’m very dubious about the next release of the upgrade, Angus. It has at least one mitochondrial module that’s not documented at all.”

“That’s impossible!” cried Angus, shocked. “It’d never get through.”

“It’s got this far,” said Catriona. “No record of testing, either. I keep objecting, and I keep getting told it’s being dealt with or it’s not important or otherwise fobbed off. The release goes live in a month, Angus. There’s no way that module can be documented in that time, let alone tested.”

“I don’t get it,” said Angus. “I don’t get it at all. If this were to get out it would sink Syn Bio’s stock, for a start. Then there’s audits and prosecutions…the Authority would break them up and stamp on the bits. Forget whistle-blowing, Catriona, you should take this to the Authority in the company’s own interests.”

“I have,” said Catriona. “And I just get the same runaround.”

“What?”

If he’d heard this from anyone else, Angus wouldn’t have believed it. The Human Enhancement Authority’s reputation was beyond reproach. Impartial, impersonal, incorruptible, it was seen as the very image of an institution entrusted with humanity’s (at least, European humanity’s) evolutionary future.

Angus was old enough to remember when software didn’t just seamlessly improve, day by day or hour by hour, but came out in discrete tranches called releases, several times a year. Genetic tech was still at that stage. Catriona’s employer Syn Bio (mostly) supplied it, the HEA checked and (usually) approved it, and everyone in the EU who didn’t have some religious objection found the latest fix in their physical mail and swallowed it.

“They’re stonewalling,” Catriona said.

“Don’t worry,” said Angus. “There must be some mistake. A bureaucratic foul-up. I’ll look into it.”

“Well, keep my name out of—“

The lights came on for Earth Hour.

“That won’t be easy,” Angus said, flinching and shielding his eyes as the balcony, the room, the building, and the whole sweep of cityscape below him lit up. “They’ll know our connection, they’ll know you’ve been asking—“

“I asked you to keep my name out of it,” said Catriona. “I didn’t say it would be easy.”

“Look into it without bringing my own name into it?”

“Yes, exactly!” Catriona ignored his sarcasm–deliberately, from her tone. She looked around. “I can’t concentrate with all this going on. Catch you later.”

Angus waved a hand at the image of his sister, now ghostly under the blaze of the balcony’s overhead lighting. “I’ll keep in touch,” he said dryly.

“Bye, bro.”

Catriona faded. Angus lit his small cigar at last, and sipped the whisky. Ah. That was good, as was the view. The Sydney Harbour was hazy in the distance, and even the gleaming shells of the Opera House, just visible over the rooftops, were fuzzy at the edges, the smart dust in the air scattering the extravagant outpouring of light. Angus savored the whisky and cigar to their respective ends, and then went out.

On the street the light was even brighter, to the extent that Angus missed his footing occasionally as he made his way up Macleay Street towards Kings Cross. He felt dazzled and disoriented, and considered lowering the gain on his eyes–but that, he felt in some obscure way, would not only have been cheating, it would have been missing the point. The whole thing about Earth Hour was to squander electricity, and if that spree had people reeling in the streets as if drunk, that was entirely in the spirit of the celebration.

It was all symbolic anyway, he thought. The event’s promoters knew as well as he did that the amount of CO

2

being removed from the atmosphere by Earth Hour was insignificant–only a trivial fraction of the electricity wasted was carbon-negative rather than neutral–but it was the principle of the thing, dammit!

He found a table outside a bar close to Fitzroy Gardens, a tree-shaded plaza on the edge of which a transparent globe fountained water and light. He tapped an order on the table, and after a minute a barman arrived with a tall lager on a tray. Angus tapped again to tip, and settled back to drink and think. The air was hot as well as bright, the chilled beer refreshing. Around the fountain a dozen teenagers cooled themselves more directly, jumping in and out of the arcs of spray and splashing in the circular pool around the illuminated globe. Yells and squeals; few articulate words. Probably cortexting each other. It was the thing. The youth of today. Talking silently and behind your back. Angus smiled reminiscently and indulgently. He muted the enzymes that degraded the alcohol, letting himself get drunk. He could reverse it on an instant later, he thought, then thought that the trouble with that was that you seldom knew when to do it. Except in a real life-threatening emergency, being drunk meant you didn’t know when it was time to sober up. You just noticed that things kept crashing.

He gave the table menu a minute of baffled inspection, then swayed inside to order his second pint. The place was almost empty. Angus heaved himself onto a barstool beside a tall, thin woman about his own age who sat alone and to all appearances collected crushed cigarette butts. She was just now adding to the collection, stabbing a good inch into the ashtray. A thick tall glass of pink stuff with a straw anchored her other hand to the bar counter. She wore a singlet over a thin bra, and skinny jeans above gold slingbacks. Ratty blond hair. It was a look.

“I’ve had two,” she was explaining to the barman, who wasn’t listening. She swung her badly aimed gaze on Angus. “And I’m squiffy already. God, I’m a cheap date.”

“I’m cheaper,” said Angus. “Squiffier, too. Drunk as a lord. Ha-ha. I used to be a lord, you know.”

The woman’s eyes got glassier. “So you did,” she said. “So you did. Pleased to meet you, Mr. Cameron.”

“Just call me Angus.”

She extended a limp hand. “Glenda Glendale.”

Angus gave her fingers a token squeeze, thinking that with a name like that she’d never stood a chance.

“Now ain’t that the truth,” Glenda said, with unexpected bitterness, and dipped her head to the straw.

“Did I say that out loud?” Angus said. “Jeez. Sorry.”

“Nothing to be sorry about,” Glenda said.