Earthly Crown (69 page)

Authors: Kate Elliott

“But surely—” Echido hesitated. “Tai-en, every princely and ducal house holds to itself a

motto,

I believe you would name it in your tongue. Said thus, it illuminates both the noble lord himself and what his family has created in his name.”

“Ah,” said Charles. “Of course. How did you know the Mushai’s motto? Surely it has been a long time since his name was spoken in the halls of the emperor.”

“Uncounted years,” said Echido. “Tai-en.” He bowed. “But all know it, still, because its very words are—as reckless as he was. So it remains with us, over time uncounted and years beyond years. ‘This hand shall not rest.’ That is one way it might translate into your language, although I am sure the Tai-endi Terese could render a more accurate, fitting, and poetic translation.”

“I am sorry,” said Charles, “that she is not here to see this.”

“I, too, Tai-en, am saddened by her absence. Our acquaintance was brief, but I count myself favored that she dignified my presence with her attention.” He folded his hands in front of him. David knew that the arrangement of fingers and palm had meaning, that it signified an emotion, a statement, a frame of mind, but he could not interpret it. Tess could, but Tess wasn’t here. No wonder Charles refused to let her go. She was invaluable to his cause.

“We must go,” said Charles. “I hope no one was awake to see this display, however much I am pleased to have seen it myself. Otherwise there could be awkward questions.” He started to walk. Maggie let go of David’s hand and paced up beside the Chapalii merchant. David fell in next to Charles. They paused at the buttressed arch that led into a long hall lined with alternating stripes of pale and black stone. Echido and Maggie kept walking, but Charles turned to look back into the vast hollow behind them. From this angle, no lights shone, not even faint ones. It was as black as a cave. Only the immensity of air, palpable as any beast, betrayed the cavernous gulf beyond.

“So what will your motto be?” David asked, half joking.

“I’ve been reading

The Tempest

lately,” said Charles, his voice as colorless as Echido’s. “After what Maggie said. There’s a little phrase the sorcerer Prospero says to the spirit Ariel, who serves him.” Here in the darkness, David felt more than saw Charles’s presence, familiar and yet strange at the same time, here, where he might learn what lay now at Charles’s heart. Charles still faced the huge chamber of the dome. His breath exhaled and was drawn in. On the next breath, he spoke.

“‘Thou shalt be free.’”

I

WOULD LIKE TO

thank the San Jose Repertory Theatre, and in particular John McCluggage and the cast and crew of the Spring 1992 production of Noel Coward’s

Hay Fever,

for graciously allowing me to attend rehearsals. If I got anything right about acting and theater, it’s because of them, and because of additional comments by Carol Wolf, Nancy E. Bottem, and Howard Kerr. Exaggerations and inaccuracies are my own.

I would also like to thank Edana Vitro, for photocopying above and beyond the call of duty, and the many readers who made excellent comments on the early drafts.

Turn the page to continue reading from the Novels of the Jaran

“He, who the sword of heaven will bear

Should be as holy as severe . . .”

—SHAKESPEARE,

Measure for Measure

A

LEKSI COULD NO LONGER

look at the sky without wondering. On clear nights the vast expanse of Mother Sun’s encampment could be seen, countless campfires and torches and lanterns lit against the broad black flank of Brother Sky. Uncle Moon rose and set, following his herds, and Aunt Cloud and Cousin Rain came and went on their own erratic schedule.

But what if these were only stories? What if Tess’s home, Erthe, lay not across the seas but up there, in the heavens? How could land lie there at all? Who held it up? Yet who held up the very land he stood on now? It was not a question that had ever bothered him before.

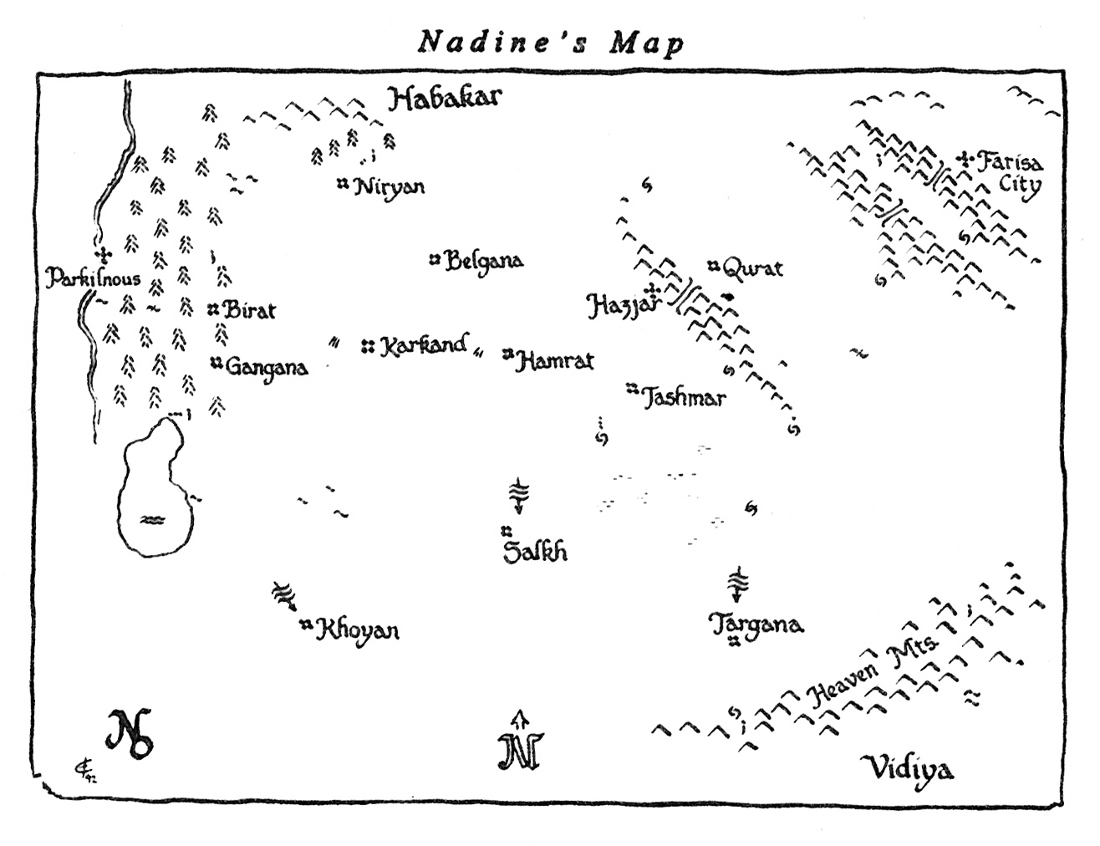

He prowled the perimeter of the Orzhekov camp in the darkness of a clear, mild night. Beyond this perimeter, the jaran army existed as might any great creature, awake and unquiet when it ought to have been resting; but the army celebrated another victory over yet another khaja city. And in truth, the camp still rejoiced over the return of Bakhtiian from a terrible and dangerous journey. The journey had changed him from the dyan whom they all followed in their great war against the khaja into a gods-touched Singer through whom Mother Sun and Father Wind themselves spoke.

And yet, if it was true that Tess and Dr. Hierakis and Tess’s brother the prince and all his party came from a place beyond the wind and the clouds, beyond the moon and the sun, then to what land had Bakhtiian traveled? To whom had he spoken? By whom was he touched? And how could a land as large as the plains lie up there in the sky, and Aleksi not be able to see it?

The stars winked at him, mute. They offered no answers, just as Tess had offered no answers before he had discovered that there was a question to be asked.

From here he could see the hulking shadow of Tess’s tent at the very center of the camp—not just at the center of the Orzhekov tribe but at the heart of the entire army. Another, smaller shadow moved and he paused and waited for Sonia to catch up to him.

She rested a hand on his sleeve and he could tell at once—although he could not see her face clearly—that she was worried. “Aleksi,” she said, whispering although they were already private. “Have you seen Veselov?” She hesitated, and he heard more than saw her wince away from continuing. But she went on. “Vasil Veselov. He came through camp earlier. He

said

he came to ask Niko about one of his rider’s injuries, but I don’t believe—” She faltered.

Aleksi was shocked at her irresolution.

“No one has seen him leave,” Sonia continued. “And Ilya just came back…” She trailed off and flashed a look around to make sure no one was close enough to hear, despite the fact that they both knew that they were well out of earshot, and that no one walked this way in any case. This part of camp, unlike the rest of the huge sprawl of tents extending far out into the darkness, was quiet and subdued. “The guards didn’t see him, but you never miss anything, Aleksi.” She waited.

A discreet distance beyond the awning of Tess’s tent stood the ever-present guards, these a trio who had ridden in with Ilya. Aleksi had seen him arrive with a larger train and then dismiss most of them. Bakhtiian had gone into his tent alone.

“Oh, I saw Veselov leave camp,” Aleksi lied in a casual voice. It wasn’t true, of course. But Aleksi knew when to trust his instincts. Better that no one else realize where Veselov actually was.

“Thank the gods,” murmured Sonia on a heartfelt sigh, and she gave Aleksi a sisterly kiss on the cheek and returned, presumably lighter in spirit, to her own tent.

It made Aleksi feel sick at heart, to lie to her like that, but he had learned long ago that orphans, outcasts, and all outsiders could not always live by the truth, though they might wish to. He trusted Tess to know what she was doing, just as she trusted him to protect her. No greater bond existed than love sealed by trust.

Aleksi touched his saber hilt and glanced up at the stars again. He wondered if Tess had not become like a weaver whose threads grow tangled: If the damage is not straightened and repaired soon enough, the cloth is ruined. Wind brushed him, sighing through camp. Songs drifted to him on the breeze, a distant campfire flared and, closer, a horse neighed, calling out a challenge. Above, in the night sky, the campfires of Mother Sun’s tribe burned on, too numerous to count, too distant to smell even the faintest aroma of smoke or flame from their burning.

“We come from a world like this world,” Dr. Hierakis had said, “except its sun is one of those stars.” Could there possibly be another Mother Sun out there, giving her light to an altogether different tribe of children? He shook his head impatiently. How could it be true? How could it not be true? And what, by the gods, did Tess think she was doing, anyway? Did she truly understand what trouble there would be if it was discovered that Bakhtiian and Veselov had met together, secretly, even with her serving as an intermediary?

He cast one last glance at the silent tent and then began to walk the edge of camp again.

I

LYA LAY IN ELEGANT

disarray beside her, breathing deeply, even in sleep marked by a harmonious attitude that drew the eye to him. A soft gloom suffused the tent. The lantern burned steadily, but its light did little more than blur the edges of every object in the chamber.

Vasil was one such object: the light burnished his hair and accentuated the planes of his handsome face. He lay on his side with his eyes shut, but Tess knew he was only pretending to be asleep. Somehow, not surprisingly, she had ended up between the two men. She traced her fingers up his bare arm to his shoulder.

“Vasil,” she whispered, so as not to wake Ilya, “you have to leave.”

He did not open his eyes. “If you were a jaran woman,” he said, no louder than her, “you would have repudiated him, and never ever done such a thing as this. What is it like in the land where you come from?”

“In the land where I come from, there are marriages like this.”

His eyes snapped open. He looked at her suspiciously. “Two men and a woman?”

“Yes, and sometimes two women and a man, sometimes two of each. It’s not common, but it exists.”

“Gods,” said Vasil. He smiled. “Ilya must conquer this country.”

“No,” said Tess, musing. “It’s a long way away.”

“I never heard of such a thing in Jeds,” said Ilya.

“I thought you were asleep! It isn’t Jeds, anyway. It’s Erthe.”

“Ah,” said Ilya. He shifted. She turned to look over her shoulder at him, but he was only moving to pull the blankets up over his chest. “Tess is right. You have to go, Vasil.”

Lying between them, Tess was too warm to need blankets. Vasil reached out to draw a hand over her belly, casual with her now that they had been intimate.

“Not much here. You must be early still, like Karolla.”

Tess chuckled. “Dr. Hierakis says I’m not quite halfway through. She says with my build that I carry well.”

“Dokhtor Hierhakis?

Ah, the healer. She came from Jeds.”

“From Erthe, originally, but she lives in Jeds now.”

“How can she know, Tess?” asked Ilya suddenly.

For once, there was a simple, expedient answer, and she didn’t have to lie to him. “Because you got me pregnant after you came back from the coast with Charles. I know I wasn’t pregnant before that. Ilya, if you think back, you know as well as I when it happened.”

“I’m sorry I—” began Vasil, and then stopped. He withdrew his hand from her abdomen and sat up abruptly.

“You’re sorry about what?” Tess asked.

“Nothing.” He shook his head. Tess watched, curious. She had never seen Vasil at a loss for words before.

“You’re sorry you weren’t there,” said Ilya in a low voice, “and you’re sorry to think that I might have a life with my own wife that doesn’t include you.”

Vasil did not reply. He rose and dressed without saying anything at all. Tess could tell that he was troubled. She watched him dress, unable not to admire his body and the way he moved and stood with full awareness that someone—in this case she—was watching him. She could feel that Ilya watched him, too, but she knew it was prudent not to turn to look. Vasil did not look at either of them. He pulled on his boots and bent to kiss her. Then he stood and skirted the pillows, only to pause on the other side, beside Ilya. Tess rolled over.

The light shone full on Vasil’s face. “Are you sorry I came here tonight?” he asked, his attention so wholly on Ilya that Tess wondered if Vasil had forgotten she was there.

Ilya regarded him steadily. “No.” His gaze flicked toward Tess and away. His voice dropped to a whisper. “No, I’m not sorry.” Vasil knelt abruptly and leaned forward and kissed him. Lingered, kissing him, because Ilya made no move, neither encouraging him nor rejecting him, just accepted it.

Simple, ugly jealousy stabbed through Tess. And like salt in the wound, the brush of arousal.