Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 (24 page)

Read Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 Online

Authors: Christine Alexander,Mason Kunze

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027100

The extremely heavy tanks that accompany the attack are much more dangerous. Our defense, including artillery as well as tank fire, is virtually powerless against these rolling monsters. Tank shells in addition to special ammunition are deflected without effect from the heavy armor. Without obstruction, the Red fighting vehicles crisscross over rubble and our positions. On deck at the very top are eleven to twelve boys, who have in their pockets tins of our “Schoko-Ka-Kola” [chocolate provided to German soldiers], and in their fists hand grenades which they are throwing into our defensive lines. At first we did not take them seriously, these hoodlums, but soon we come to know better. Tough and agile like cats, they make us suffer considerable losses. They have a whole company of these dangerous children, the “Proletariat Young Guard,” over there.

I struggle to describe in detail the horror of the hand-to-hand fighting with these children. Anyone who has not been here will never be able to understand what unfolds here. Grown men, many of whom have sons who are the same age, have had to engage in brutal, bloody fights with the children! I will not be able to forget these horrible scenes for a long time.

Parallel to the northern position, there runs a gorge into which our guns are only able to fire with difficulty. This is a most favorable deployment area for the Red Army. When the wind is favorable, we can hear from the frontline trenches the screaming and cursing of the commissars, and shortly thereafter, two, three gun shots, then the screams of the victims, and finally the silence of the grave.

A few minutes later, they rise in white masses out of the gorge and run by the hundreds, driven by the mad force of their

politniks

, right into our deadly machine gun fire. Prisoners and deserters tell us about the terrible losses suffered over there. The commissars’ pistols, the fear of a bullet to the neck, drives this herd forward again and again. When the enemy attack collapses on February 11, their own grenades are thrown into the masses who are flooding back.

We are not afraid of such a crowd, which is forced, out of its own fear, to attack us. If only the murderous artillery fire, which rips just about everything on our side to shreds, would come to an end. If only we had weapons that could crush the tanks playing this murderous game with us.

On February 12, our last two cannons are run over by 52-ton tanks. Supported by a number of aircraft, the Reds attempt a large-scale offensive around noon. For a day and a night, there is bitter fighting over the higher elevation positions. Our losses are exceptionally high; the average company size is now only about 30 men!

Slowly, very slowly, despair creeps into the hearts of our men. We group leaders have to use all our power to keep the men alert and ready to fight and defend. A difficult task indeed! Our words sound utterly unconvincing, as we ourselves no longer believe that we will make it out of here alive. Mass grave Leski!

15 February:

At the same time that the Reds commenced their large scale offensive on February 12, a 40km wide, 70km deep breach into the front line was achieved by three Bolshevik tank divisions to the south of Charkow. At this time, we know that over there Guderian [

sic

] is at the counterattack. But we also know that both breakthrough operations, here and over there near Charkow, were directly connected, which was part of the large-scale Bolshevik plan to encircle Charkow, thus isolating the northern part of 6th Army. Only through our brave and tough resistance was this undertaking successful.

16 February:

We can hardly believe it: reinforcements have arrived. The boys bring good news with them: tanks are expected to roll in soon, and even today assault guns will be deployed and used right here. My mood barometer climbs back to “nice weather.” We will hold onto our coffin, come what may!

17 February:

In the early morning hours, thirty German attack planes suddenly arrive. Like sparrow hawks, they dive into the damned battery positions near Schochowo. All over the place, dirt and metal spew upward in high fountains. For today, though, all is quiet; at night everybody gets a few hours sleep for the first time in a long while.

18 February:

Yesterday’s air raid not only destroyed several of the enemy’s guns and cannons, it also squashed the Red’s preparations for the attack that was to follow. Today, too, our air comrades appear around noon; in three waves of ten, they plunge, howling into the enemy position. Thick yellow-black smoke stands for minutes above the gorge on the other side.

19 February:

At dawn, completely to our surprise, heavy tank forces suddenly attack. Accompanied by two battalions of Caucasian sharpshooters, they succeed in breaking through on the right and left flanks of the “coffin”; by 1300 hours, Leski has been hopelessly encircled. The Morse code from our signals unit is never silent. SOS calls go out to the north and the south, to the division and the corps. We receive the same answer from both sides: “Reinforcements have left 3576 (Jakoblewo) on 2-18 in the direction of L.”

Damn it, they should have been here long ago! What are we to know about the fact that somewhere between Jakoblewo and here, a decorated soldier has fought his first and last fight? Why we are not informed about such events will forever be a mystery to us. Men marching in their battalion, 180 comrades bound for Leski, who have never encountered active battle, were massacred like animals by the Reds last night! But what do we know about that! The night turns awful! With out pause, the Asians run up our hill. Again and again, we encounter murderous close-range fighting. For how long will we be able to hold out? Where are our replacements? We have very little ammunition left. Well then, shoot slowly and don’t forget to save the very last bullet! At dawn, Oles dies, the fifth and last man of my group, from bayonet wounds to the chest. We are all slowly facing the end. Too bad, living has been so beautiful!

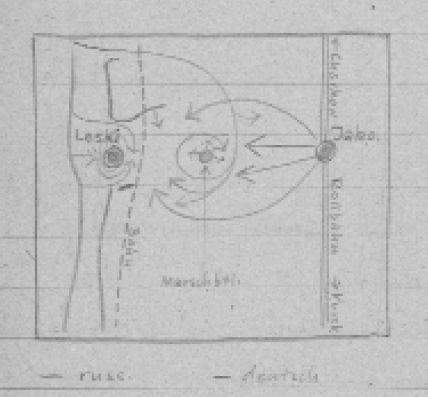

A sketch of the Luftwaffe attack on February 18 that pounded Soviet artillery and infaantry positions. “Jabo” was German slang for Jagdbomber (fighter bomber).

20 February:

Despite the snowstorm, which has picked back up, we are able to hear very faint artillery fire in the west. Could this be our savior? The attacks from Leski are becoming weaker and weaker by the hour, and end completely by around noon.

Suddenly, several bombers appear. We take cover with lightning speed. But this time they are Heinkels, which circle two or three times, and then deploy the much sought after ammunition and supplies.

A few of our tanks and shooters are approaching from the west! Replacements and guard changes! I see quite a few guys, strong as bears, with tears in their eyes. During the night a reconnaissance patrol makes contact with the relief troops arriving from the west.

21 February:

The Reds are retreating and flee to the east. At 0900 hours, German tank forces reach Leski! The reception is indescribable. Full of deep joy and gratitude, we embrace our “black brothers,” our saviors. After a short break they begin to storm the enemy’s position. We cannot allow the Reds any room to breathe; we have to clean up over there finally, once and for all.

The afternoon passes with the orientation of the new replacements.

22 February:

Relieved! A small number of dirty, dilapidated soldiers pass the area where our dead comrades lie. Half of them will remain here; here on top of the “coffin,” these brave men have found their final resting place. We have dug three large mass graves. The Red shells have done their dirty work here as well. The ground has been ploughed from strong explosions, the contents of the graves scattered, ripped apart for the second or third time. An even more gruesome one will soon replace this horrible picture.

After a four-hour march, we reach the location where the Reds butchered the 180 men of the marching battalion. These animals, these sub-humans, even had the time to mutilate the naked bodies of the dead soldiers and pile them up in large heaps. According to information from prisoners, these

schweine

even took a dozen photos of this place of horror. (Four weeks later, on March 25, hundreds of thousands of leaflets with reproductions of these pictures are dropped over Charkow-Bjelgorod.)

Physically and emotionally exhausted, our small group reaches Jakoblewo at dusk. Although everyone here knows the sorry sight of the Leski relief unit, this time someone turns his head around to look. We all resemble mad men: full beards cover our pale faces. Some of us are wearing Russian caps, while others are wearing the yellow-brown Red Army coats, sheep pelts, and sacks wrapped around their boots. Besides our weapons, we no longer have any gear left—no blankets, no bread bags, no water bottles or cooking utensils; everything, and I mean everything, has been completely destroyed for a third time on February 20. Now, two sleds are sufficient enough to pull away the last two machine guns. Our three cannons are lying shredded and overrun at the “coffin.”

23 February:

Back in Obojan. Those days in Leski have affected us deeply on the outside as well as on the inside. Some are suffering from a bad case of nerve fever, others from severe frostbite. Rheumatism is also rampant. My leg hurts badly, probably from the last wound. But shit, we are soldiers and not old wives! And if any one of us has a nervous breakdown out here, so be it—later, at home, the love and patience of our wives will heal many surface and inner wounds.

24–28 February:

On all sides of the front, heavy defensive battles are being fought. The winter that the Reds have placed all their hopes on is coming to an end. It is still terribly cold, icy blizzards are still whipping over the vast plains. “Now or never” is the motto which Stalin uses to force hundreds of thousands to run and bleed to death. We have reached the climax of the winter battle. Everybody performs like a super hero these days.

All sections of the unit, with their last reserves, take part on the defensive line. Defense means to ward off the enemy. Warding off does not imply waiting until the enemy arrives, until he takes the initiative and determines the outline of the battle. Warding off also demands counterattacks and engaging in reconnaissance patrols to find out the enemy’s intentions in order to beat him while his strategies and plans of action are taking shape. Warding off means conducting small skirmishes to acquire favorable positions. It not only means being consistently on guard, standing one’s ground in murderous artillery fire, holding out during attacks from the air, but also standing up to the power of tanks. It demands being prepared day and night. Warding off also means not being tired for a single second, always having your hands on your weapon. This eats at your nerves and takes its toll on the depleted strength of your body and soul.

At home, they will never be able to have even a remotely accurate picture of the demands that this defensive fight in the East requires of us: exhaustion, mobilization of will power, and personal sacrifice! Up front are the infantrymen, then us, the tank hunters, their eternal companions and most faithful friends! We are the front line, closest to the danger. During these months, we have seen nothing but snow, enemies, and desolate vastness; we experience nothing but danger and the battle of man versus nature.

For days, our boots do not come off our legs, and the warmth of a stove is far away. The cold temperatures and snowstorms shake us through and through, and even when we eat, one hand is always on our gun. One ear is always trained to the outside, listening for the enemy—even during those hours when combat has died down.

Doubling one’s own commitment and strength is required to compensate for the holes that death rips into our lines; the unwritten law of brotherhood and the moment’s necessities demand nothing less. I could give hundreds of gut-wrenching examples and incidents of such selfless comradeship among us

frontschweine

.

What makes these defensive battles here in the east so hard and filled with deprivation is the sheer mass of men and material that the enemy throws at our front ruthlessly and relentlessly. It is the battle against the snow, cold, and ice. These are the difficult hours, when ammunition becomes scarce and when from the other side, more and new waves of men are thrown at us. These are the difficult hours when the soldier at the front line is waiting in vain for food and drink, because the supply truck is stuck in a snowstorm. This is what it was like in Leski, when the superior force appears to be suffocating. These are also the trying hours for the leaders who are often confronted with the decision, “Shall we hold out any longer? Haven’t we already done everything humanly possible?” And still, none of us complains, we, who hold watch in the lonely foxholes of the East. None of us thinks of giving up hope just because a meal is missing. None of us thinks of cursing because our bodies have not felt the warmth of a stove for so long. We know that all of this is asked of us because the greater purpose of the war demands it of us.