Eat Him If You Like (9 page)

Read Eat Him If You Like Online

Authors: Jean Teulé

Dordogne Criminal Court

(Special Session)

Presided by Judge Brochon, justice of the Bordeaux

Court of Appeal

The Hautefaye affair

Murder of Alain de Monéys

Twenty-one men stood accused.

On 13 December 1870, at seven o’clock in the evening, the High Court reached a verdict on those accused of the Hautefaye murder.

The following were sentenced:

Pierre

Buisson

, François

Chambort

, François

Léonard

(known as Piarrouty) and François

Mazière

– death penalty.

The execution will take place in Hautefaye village square.

Jean

Campot

– hard labour for life.

Étienne

Campot

– eight years’ hard labour.

Pierre

Besse

– six years’ hard labour.

Jean

Beauvais

, Jean

Frédérique

, Léonard

Lamongie

,

Antoine

Léchelle

, Mathieu

Murguet

, Pierre

Sarlat

– five years’ hard labour.

Jean

Sallat

(known as Old Moureau) – five years’ imprisonment, in consideration of his age (sixty-two).

Jean

Brouillet

, Pierre

Brut

, Girard

Feytou

, Roland

Liquoine

, François

Sallat

, accused of the lesser offence of actual bodily harm – one year’s imprisonment.

Thibault

Limay

(known as Thibassou) has been cleared, in consideration of his age (fourteen) and that he acted rashly, but he shall be sent to a reform institution until he reaches his twentieth birthday.

Pierre

Delage

(known as ’Poleon), having acted rashly, is acquitted due to his age (five) and he is granted his freedom.

‘There aren’t many people. Less than a hundred, I reckon.’

‘I could have sworn there were more on the day of the fair … I can’t see Alain’s parents. Didn’t they want to come?’

‘Didn’t you hear? His mother died of grief last autumn. On 31 October, I believe.’

‘What about his father?’

‘He has sold off the Bretanges estate, all two hundred acres, and put the house up for sale too. He’s left the area. He didn’t really want to keep bumping into the men who murdered and ate his son.’

The two men hopped up and down in the snow and rubbed their arms in an attempt to keep warm.

‘Brr! You can tell it’s 6 February. It was much warmer here on 16 August. Did you know they’re going to demolish the village?’

‘What, destroy Hautefaye?’

‘The government is seriously thinking about wiping the village from the map.’

Daybreak came, and with it a feeling of subdued anxiety. The moon was still visible. It unveiled half of its hypocritical face, feigning pity.

‘Shall we go closer to the horrible contraption?’ suggested one of the men. ‘I’ve not seen one before.’

‘It’s very rare that they bring a guillotine to the scene of the crime.’

Four pine coffins, their bases covered in sawdust, stood by the guillotine where the executioner was talking to his assistants. The lids were placed to one side. A whistle of metal followed by a solid thud made the two men jump. The executioner had asked his assistant to raise the blade by pulling on the rope and was checking that it fell correctly. The prosecutor took a watch from his waistcoat pocket.

‘Seven twenty-five; are you ready?’

The executioner, who was wearing a top hat, nodded.

‘Attention!’ barked a moustachioed captain. His order was followed by the sound of heels clicking in the pale dawn light. One hundred gendarmes formed a stalwart line from the door of Mousnier’s inn to the corn exchange. Behind them came stifled sobs from friends and relatives of the condemned men and from wives wearing black woollen shawls. The door of the renovated inn opened.

Piarrouty was the first to emerge from Mousnier’s establishment, which had acted as a temporary jail before the execution. A boy slipped between two gendarmes and held out a cup of coffee. The prosecutor nodded his assent. The ragman drained the cup slowly and then handed it back to the child, gazing at him as though he were his own son.

‘My boy, be good and never behave as I did. If ever you feel the urge to hit your neighbour, just throw away your axe and be on your way.’

A few seconds later and Piarrouty’s steaming blood could

be seen on the block. In a way, it was as though everyone in the village had been executed. Shutters were closed around the square, but there was still the feeling that, behind the blinds, people were pressing their faces to the windowpanes. Now it was Buisson’s turn.

‘None of my family is here? Are they still disgusted with me?’

‘I will talk to your wife and children,’ said the priest, who was supporting him.

‘Tell them I’m a swine and I’m sorry for what I did.’

Buisson’s head rolled into the basket of sawdust, on top of Piarrouty’s, and Mazière soon joined them. He had died whimpering, ‘

Maman, Maman

,’ like an injured nightingale.

‘We were once good people, you know,’ sighed Chambort.

A large dappled horse with steaming nostrils pulled a cart carrying the four sealed coffins to a communal grave in the cemetery. Drummers, scarlet uniforms and black horses were gathered in front of the corn exchange. Élie Mondout’s inn filled rapidly. Each table ordered several drinks, which were promptly served, but on this freezing February morning, people were feeling hungry as well.

‘What’s there to eat?’

‘To eat? Well, there’s still some barley soup of course!’ replied Élie Mondout. ‘Anna, pour the drinks, cut the bread, fill the plates! Anna!’

The executioner’s assistant was asking a gaunt-looking Anna for a tub of hot water to wash his clothes in. Her teeth started chattering uncontrollably.

Inside the inn, people talked about the police wagons carrying the men sentenced to hard labour that had left for

La Rochelle and then onto Nou Island in New Caledonia.

‘Where’s New Caledonia?’

A cattle farmer wondered aloud whether France’s most peaceful village had been permanently sullied. Subsequently, people moved on to a rather confused political ‘debate’.

‘Where’s Anna?’ asked Élie Mondout.

‘Not in the kitchen, nor down in the cellar fetching wine. We would have seen her if she’d left though,’ replied his wife. Élie Mondout opened the small back door and surveyed the surrounding countryside.

‘Anna! Anna!’

The innkeeper stood at the door, bellowing. His shouts and the rush of air from the open door created a gust that carried off a fleck of ash that had perhaps been there since the previous summer.

‘Anna! Anna!’

Anna lay face down in the snow – dead.

‘She was there all along, on the frozen marshes of the Nizonne. No wonder it took you so long to find her …’

Dr Roby-Pavillon walked round the dead girl, footsteps crunching in the snow. He was followed by a distraught Élie Mondout and the villager who had discovered her.

‘One of my cows got out and I wanted to check she hadn’t got stuck near the river.’

The pathologist crouched down, sliding a professional hand under the girl’s heavy jacket.

‘She was six months pregnant,’ he diagnosed.

‘What?’ gasped Anna’s uncle, horrified.

‘I wonder if that has anything to do with what’s written here,’ mused the doctor, straightening up and wiping his hands on his black trousers encrusted with snow.

‘I can’t read. What does it say?’ asked the villager, going over to the giant letters drawn in the snow.

The twenty-three-year-old girl who had once ironed clothes in Angoulême lay still, her head to one side. She wore a thick woollen dress and clumsy hobnail shoes. Lying there, deathly pale and with crystals of frost on her

eyelashes, her beautiful lips parted, she looked as if she were simply asleep.

The conscience of the cannibal village, Anna lay on the frozen grass, which had been completely flattened. The louring sky cast a grey mist over the snow. Near Anna’s mouth and frozen index finger were written the words ‘I love you’.

‘I love you? But who’s that for? I never saw her look at any boy except Alain de …’ said Élie Mondout, dumbfounded.

‘It looks like one of the magic mirrors the tinkers take from their suitcases,’ said the villager, entranced.

‘Six months, you say, Doctor?’ asked the dead girl’s uncle, counting backwards. ‘February, January, December … She would have conceived mid-August?’

‘That’s right.’

‘But who by? It can’t have been the day of the …’

‘And how did she learn to write?’ asked the villager, walking around the letters and admiring them upside-down.

‘The schoolmaster’s wife taught her,’ replied Élie Mondout hollowly.

The villager continued his orbit, finding himself looking at the letters the right way up.

‘Either way, the words are big enough to be visible from heaven.’

A speck of ash fluttered down, seemingly from the clouds, and landed on Anna’s frosted lip, melting there like a kiss. The doctor and the innkeeper exchanged glances.

‘No, it’s impossible! How could he have done it? It was that very day, you know!’ exclaimed Élie Mondout.

‘But he was kept otherwise occupied by everybody else!’

agreed the doctor.

‘It’s the

lébérou

!’ cried the villager, as if in a trance. ‘Under the evil spell, his body wrapped in an animal skin, he probably jumped on the girl’s back, got her pregnant, and then took on the shape of an innocent neighbouring villager. We need to find out who it is – which one of us – and really show him, show that Prussian what we’re made of. With sticks and …! Oh, I swear …!’

The mayor of Nontron gazed at the little ripples of the Nizonne and the blue roofs of Hautefaye. Standing wistfully at the water’s edge, he listened to the song of the gorse and the reeds.

On arrival at the prison camp on Nou Island, the men sentenced to hard labour for the Hautefaye murder were given nicknames by other convicts. There was ‘Lamb chop’, ‘Well cooked’, ‘Medium rare’, ‘Grilled steak’ and more. Jean Campot was given Alain’s surname and soon became accustomed to it. After thirty years of hard labour, he was released for good conduct. He stayed in New Caledonia and had children with a Kanak woman, who took the surname de Monéys as well.

On 16 August 1970, descendants of the de Monéys and the killers’ families held a mass to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the event, which they all attended together. The mass was celebrated in Hautefaye’s church – the village had not been wiped off the map after all.

Alain de Monéys’s project to divert the Nizonne was accomplished and, one hundred and fifty years on, the region is still thriving as a result.

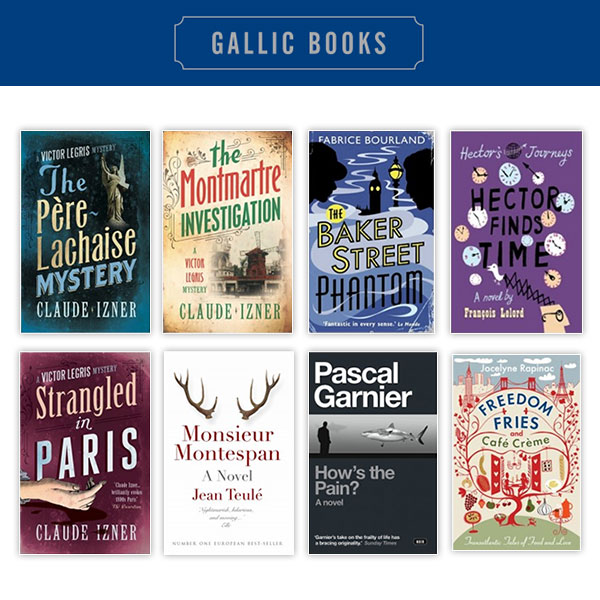

Jean Teulé

lives in the Marais with his companion, the French film actress Miou-Miou. An illustrator, filmmaker and television presenter, he is also the prize-winning author of eleven books including

The Suicide Shop

.

Emily Phillips

studied French and Spanish at the University of Bath. She lives and works in Bristol.

The Suicide Shop

Monsieur Montespan

First published in 2011

by Gallic Books, Worlds End Studios, 134 Lots Road,

London, SW10 ORJ

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© JeanTeulé, 2011

The right of JeanTeulé to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

ISBN 978

–

1

–

908313

–

17

–

1 ebook

ISBN 978

–

1

–

908313

–

18–8 pdf