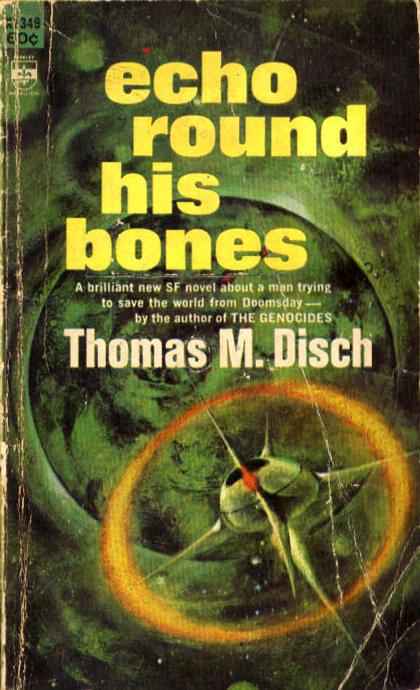

Echo Round His Bones

Read Echo Round His Bones Online

Authors: Thomas Disch

60¢

Berkley

Medallion

echo

round

his

bones

The brilliant new SF novel about a man trying

to save the world from Doomsday --

by the author of THE GENOCIDES

Thomas M. Disch

SINKING INTO TROUBLEMedallion

echo

round

his

bones

The brilliant new SF novel about a man trying

to save the world from Doomsday --

by the author of THE GENOCIDES

Thomas M. Disch

Worsaw shot the private three times in the face. The body

crumpled backward against -- and partly through -- the

wall.

"That takes care of

one

son-of-a-bitch," said the spectral

Worsaw.

Before the man's murderous inference could be realized,

Hansard acted. In a single motion he threw himself from

the bench and the attaché case that he had been holding at

Worsaw's gun hand. The gun went off, doing harm only to

the case.

In leaping from the bench Hansard had landed on the floor

of the steel vault -- or more precisely, in it, for his hands had

sunk several inches into the steel, which felt like chilled

turpentine against his skin. This was strange, really very

strange . . . But not to be distracted from his immediate

purpose -- which was to disarm Worsaw -- he sprang up to

catch hold of Worsaw's hand, but found that with the same

movement his legs sank knee-deep into the insubstantial

floor.

echo

round

his

bones

Thomas M. Disch

round

his

bones

Thomas M. Disch

ECHO ROUND HIS BONES

NATHAN HANSARD

The finger on the trigger grew tense. The safety was released, and

in almost the same moment the gray morning stillness was shattered by

the report of the rifle. Then, just as a mirror slivers and the images

multiply, a myriad echoes returned from the ripening April hillsides --

a mirthful, mocking sound. The echoes re-echoed, faded, and died. But

the stillness did not settle back on the land; the stillness was broken.

The officer who had been marching at the head of the brief column of men

-- a captain, no more -- came striding back along the dirt track. He was

a man of thirty-five or perhaps forty years, with fair, regular features

now set in an expression of anger -- or, if not quite anger, irritation.

Some would have judged him a handsome man; others might have objected

that his manner was rather too neutral -- a neutrality expressive not

so much of tranquility as of truce. His jaw was set and his lips molded

in the military cast. His blue eyes were glazed by that years-long

unrelenting discipline. They might not, it could be argued, have been

by nature such severe features: without that discipline the jaw might

have been more relaxed, the lips fuller, the eyes brighter -- yes,

and the captain might have been another man.

He stopped at the end of the column and addressed himself to the

red-haired soldier standing on the outside of the last file -- a

master-sergeant, as might be ascertained from the chevron sewn to the

sleeve of his fatigue jacket.

"Worsaw?"

"Sir." The sergeant came, approximately, to attention.

"You were instructed to collect all ammunition after rifle practice."

"Yes, sir."

"All cartridges were to be given back to you, therefore no one should

have any ammunition now."

"No, sir."

"And this was done?"

"Yes, sir. So far as I know."

"And yet the shot we just heard was certainly fired by one of us.

Give me your rifle, Worsaw."

With visible reluctance the sergeant handed his rifle to the captain.

"The barrel is warm," the captain observed. Worsaw made no reply.

"May I take your word, Worsaw, that this rifle is unloaded?"

"Yes, sir."

The captain put the butt of the rifle against his shoulder and laid his

finger over the trigger. He remarked that the safety was off. Worsaw

said nothing.

May I pull the tngger, Worsaw?" The rifle was pointed at the sergeant's

right shin. Worsaw still said nothing, but beads of sweat had broken out

on his freckled face.

"Do I have your permission? Answer me."

Worsaw broke down. "No, sir," he said.

The captain broke open the magazine and removed the cartridge clip.

He handed the rifle back to the sergeant. "Is it possible, Worsaw,

that the shot that brought us to a halt a moment ago was fired from this

rifle?" There was, even now, no trace of sarcasm in the captain's voice.

"I saw a rabbit, sir -- "

The captain's brow furrowed. "Did you hit it, Worsaw?"

"No, sir."

"Fortunately for you. Do you realize that it is a federal offense to kill

wildlife on this land?"

"It was just a rabbit, sir. We shoot them around here all the time.

Usually when we come out for rifle practice, or that sort of stuff -- "

"Do you mean to say that it is

not

against the law?"

"No, sir, I wouldn't know about that. I just know that usually -- "

"Shut up, Worsaw!"

Worsaw's face had become so red that his reddish-blond eyebrows and lashes

seemed pale in comparison. In his bafflement his lower lip had begun to

tic back and forth, as though some buried fragment of his character were

trying to pout.

"I despise a liar," the captain said blandly. He inserted his thumbnail

under the tip of the chevron sewn on Worsaw's right sleeve and ripped

it off with one quick motion. Then the other chevron.

The captain returned to the front of the column, and the march back to

the trucks that would return them to Camp Jackson was resumed.

This captain, who will be the hero of our history, was a man of the

future -- that is to say, of what would seem futurity to us; for to the

captain it seemed the most commonplace present. Yet there are degrees

of living in the future, of being contemporary there, and it must be

admitted that in many ways the captain was more a man of the past (of

his past, and even perhaps of ours) than of the future.

Consider only his occupation: A career officer in the Regular Army --

surely a most uncharacteristic employment in the year 1990. By that

time everyone knew that the army, the Regular Army (for though the

draft was still in operation and young men were compelled to surrender

their three years to the Reserve Army, they all knew that this was a

joke; that the Reserves were useless; that they were maintained only

as a device for keeping themselves out of the labor force, or off the

unemployment rolls that much longer after college), was a career for

louts and nincompoops. But if

everyone

knew this . . .? Everyone who

was "with it"; everyone who was truly comfortable living in the future.

These contemporaries of the captain (many of whom -- some 29 per cent --

were so much unlike him as to prefer three years of postgraduate study in

the comfortable and permissive prisons that had been built for C.O.'s --

the conchies, as they were called -- rather than submit to the ritual

nonactivities of the Reserves) regarded the captain and his like as --

and this is their most charitable judgment -- fossils.

It is true that military service traditionally requires qualities more

of character than of intelligence. Does this mean, then, that our hero

is on the stupid side? By no means! And to dispel any lingering doubts

of this, let us hasten to note that in third grade the captain's I.Q.,

as measured by the Stanford-Binet Short Form, was a respectable 128 --

certainly as much or more than we can fairly demand of a hero in this

line of work.

In fact it had been the captain's experience that he possessed intelligence

in excess of his needs; he would often have been happier in his calling

if he had been as blind to certain distinctions -- often of a moral

character -- as most of his fellow officers seemed to be. Once, indeed,

this over-acuteness had directly injured the captain's prospects. And it

might be that that long-ago event was the cause, even this much later,

of the captain's relatively low position (considering his age) in the

military hierarchy. We shall have opportunity to hear more of this

unpleasant moment -- but in its proper place.

It may just as plausibly be the case that the captain's lack of advancement

was due simply to a lack of vacancies. The Regular Army of 1990 was much

smaller than the Army of our own time -- partly because of international

agreements, but basically in recognition of the fact that a force of

25,000 men was more than ample to prosecute a nuclear war -- and this,

in 1990, was the only war that the two great power blocs were equipped

to fight.

Disarmament was a fait accompli, though it was of a kind that no one of

our time had quite anticipated; instead of eliminating nuclear devices,

it had preserved them alone. In truth, "disarmament" is something of a

euphemism; what was done had been done more in the interests of domestic

economy than of world peace. The bombs that the Pacifists complained of

(and in 1990

everyone

was a Pacifist) were still up there, biding their

time, waiting for the day that everyone agreed was inevitable. Everyone,

that is, who was with it; everyone who was truly comfortable living in

the future.

Thus, though the captain lived in the future, he was very little

representative of it. His political opinions were conservative to a point

just short of reaction. He read few of what we would think of as the

better books of his time; saw few of the better movies -- not because

he lacked aesthetic, sensibilities -- for instance, his musical taste

was highly developed -- but because these things were made for other,

and possibly better, tastes than his.

He had no sense of fashion -- and this was not a small lack, for among

his contemporaries fashion was a potent force. Other-directedness had

carried all before it; shame, not guilt, was the greater shaper of souls,

and the most important question one could ask oneself was: " Am I with it?"

And the captain would have had to answer, " No."

He wore the wrong clothes, in the wrong colors, to the wrong places.

His hair was too short, though by present standards it would have seemed

rather full for a military man; his face was too pale -- he wouldn't use

even the most discreet cosmetics; his hands were bare of rings. Once,

it is true, there had been a gold band on the third finger of his left

hand, but that had been some years ago.

Unfashionableness has its price, and for the captain the price had been

steep. It had cost him his wife and son. She had been too contemporary

for him -- or he too outmoded for her. In effect their love had spanned

a century, and though at first it was quite strong enough to stand the

strain, in time it was the times that won. They were divorced on grounds

of incompatibility.

At this point it may have occurred to the reader to wonder why in a tale

of the future we should have chosen a hero so little representative of

his age. It is an easy paradox to resolve, for the captain's position

in the military establishment had brought him -- or, more precisely,

was soon to bring him -- into contact with that phenomenon which, of all

the phenomena of his age, was most advanced, most contemporary, most at

the forefront of the future -- with, in short, the matter transmitter --

or, in the popular phrase, the manmitter -- or, in the still more popular

phrase, the Steel Womb.

"Brought into contact" is perhaps too weak and passive a phrase.

The captain's role was to be more heroic than such words would suggest.

"Came into conflict" would do much better. Indeed he was to come into

conflict with much more than the Steel Womb -- with the military

establishment as well, with society in general, and with himself.

It could even be said, without stretching the meaning too far, that in

his conflict he pitted himself against the nature of reality itself.

One final paradox before we re-embark upon this tale: It was to be this

captain, the military man, the man of war, who was, at the last minute

and by the most remarkable device, to rescue the world from that ultimate

catastrophe -- the war to end wars, the Armageddon that we are all,

even now, waiting for. But by that time he would not be the same man,

but a different man; a man quite thoroughly of the future -- because he

had made it in his own image.

At twilight of that same day on which we last saw him, the captain was

sitting alone in the office of "A" Artillery Company. It was as bare a

room as it could possibly be and yet be characterized as an office. On the

gray metal desk were only an appointment calendar that showed the date

to be the twentieth of April; a telephone, and a file folder containing

brief statistical profiles of the twenty-five men under the captain's

command: Barnstock, Blake, Cavender, Dahlgren, Doggett. . . .

The walls of the room were bare, except for framed photos, cut out of

magazines, of General Samuel ("Wolf") Smith, Army Chief of Staff, and

of President Lind, whose presence here would have to be considered as

merely commemorative, since he had been assassinated some forty days

before. As yet, apparently, no one had found a good likeness of Lee

Madigan, his successor, to replace Lind's photo. On the cover of

Life

,

Madigan had been squinting into the sun; on

Time's

cover he was shown

splattered with the President's blood.

There was a metal file, and it was empty; a metal wastebasket, it was

empty; metal chairs, empty. The captain cannot be held strictly to account

for the bareness of the room, for he had been in occupancy only two days.

Even so, it was not much different from the office he had left behind

in the Pentagon Building, where he had been the aide of General Pittmann.

. . . Fanning, Green, Homer, Lesh, Maggit, Norris, Nelsen, Nelson. . . .

They were Southerners mostly, the men of "A" Company; sixty-eight per cent

of the Regular Army was recruited in Southern states, from the backwoods

and back alleys of that country-within-a-country, the fossil society

that produced fossil men. . . . Lathrop, Perigrine, Pearsall, Pearsall,

Rand, Ross. . . . Good men in their way -- that cannot be denied. But

they were not, any more than their captain, contemporary with their own

times. Plain, simple, honest men -- Squires, Sumner, Truemile, Thorn,

Worsaw, Young -- but also mean-spirited, resentful, stupid men, as the

captain well knew. You cannot justly expect anything else of men who have

been outmoded; who have had no better prospect than this; who will never

make much money, or have much fun or taste the sparkling elixir of being

"With It," who are and always will be deprived -- and who know it.

These were not precisely the terms with which the captain regarded

this problem, though he had been long enough in the Army (since 1976)

to realize that they did not misrepresent the state of affairs. But he

looked at things on a reduced scale (he was only a captain, after all)

and considered how to deal with the twenty-five men under his command so

as to divert the full force of their resentment from his own person. He

had expected to be resented; this is the fate of all officers who inherit

the command of an established company. But he hadn't expected matters to

go to such mutinous extremes as they had this morning after rifle drill.

Rifle drill was a charade. Nobody expected rifles to be used in the

next war. In much the same way, the captain suspected, this contest

of wills between himself and his men was a charade -- a form that had

to be gone through before a state of equilibrium could be reached; a

tradition-sanctioned period of mutual testing out. The captain's object

was to abbreviate this period as much as possible; the company's to draw

it out to their advantage.

The phone rang, the captain answered it. The orderly of Colonel Ives

hoped that the captain would be free to see the colonel. Certainly,

whenever it was convenient to the colonel. In half an hour? In half an

hour. Splendid. In the meantime, perhaps, it would be possible for the

captain to instruct "A" Company to prepare for a jump in the morning?

Other books

Death Angels by Ake Edwardson

Leaving Home: Short Pieces by Jodi Picoult

Mystic by Jason Denzel

A Katie Kazoo Christmas by Nancy Krulik

Not Looking for Love: Episode 3 by Bourne, Lena

Father Briar and The Angel by Rita Saladano

Rome in Love by Anita Hughes

Romance: The CEO by Cooper, Emily

Beautifully Broken by Sherry Soule