Eclipse (29 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clee

Bunbury did take what he thought were the proper steps. He hauled up Chifney to testify before him and his fellow Jockey Club stewards Ralph Dutton and Thomas Panton. Chifney, in his affidavit, swore that he had bet only twenty guineas on the race that Escape won; that he had not stopped Escape in the first

race; and that he had never profited from the defeat of a horse he had ridden or trained. The stewards were unimpressed Bunbury paid a visit to Prinny and told him that âif Chifney were suffered to ride the Prince's horses, no gentleman would start against him'.

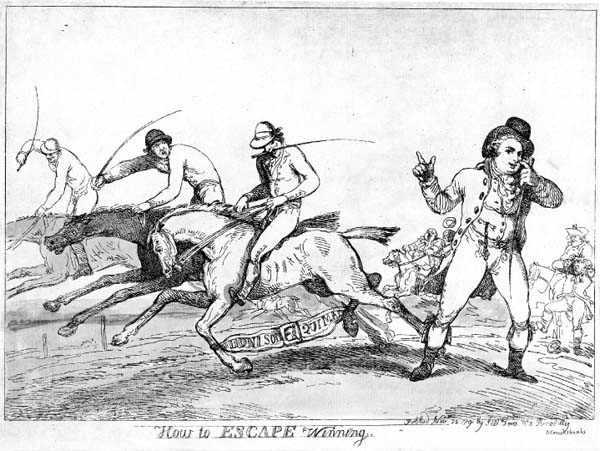

Thomas Rowlandson's view of the Escape affair,

How to Escape Winning

(1791). Sam Chifney, Escape's jockey, pulls the horse, who is further hampered by a banner saying,

âHoni soit qui mal'

(a motto that also appears in

A Late Unfortunate Adventure at York

â page 106). The Prince of Wales taps his nose knowingly at the viewer.

Here, in summary, was the new dispensation on the Turf. Just over a century earlier, Charles II had governed at Newmarket; now, the heir to the throne was being put in his place.

Prinny did not like it, and the next year he placed his stud on the market again. There are conflicting reports about whether he did so entirely because of Escape (his debts were again serious, and Escape's was not the only controversial race involving one of his horses); what is clear is that, while he was to return to the Turf once more and to race horses at Newmarket, he shunned the town until at least 1805, and probably thereafter as well, in spite of this letter from Bunbury and the Earl of Darlington:

Sir, We humbly beg leave to represent to your Royal Highness that we are deputed in our official situations as stewards of Newmarket to convey to you the unanimous wish of all gentlemen of the turf now present at Brighton, which we respectfully submit to your consideration.

From serious misconceptions or differences of opinion which arose relative to a race, in which your royal highness was concerned, we greatly regret that we have never been honoured with your presence there since that period. But experiencing as we constantly do, the singular marks of your condescension and favour, and considering the essential benefit not only that the Turf will generally derive, but also the great satisfaction that we all must individually feel from the honour of your presence, we humbly request that your Royal Highness will bury in oblivion any past unfortunate occurrences at Newmarket and you will again be pleased to honour us there with your countenance and support.

Reading the riot act to the Prince was one thing, but alienating him irrevocably was another.

Chifney, by contrast, was dispensable. Possibly the jockey had not always been honest in his riding, but on this occasion he looks like the victim of a miscarriage of justice. Everyone knows that jockeys sometimes stop horses, and that trainers leave horses unfit, or run them over inappropriate distances. However, when you look in detail at alleged incidents of these practices, you rarely find unambiguous evidence. The contemporary counterpart of Sam Chifney, certainly in respect of his unpopularity with the authorities, is the Irish-born jockey Kieren Fallon. In spring 1995, Fallon rode a beaten favourite, Top Cees, in a Newmarket handicap. Three weeks later, he rode Top Cees to an easy victory in the valuable Chester Cup, at the rewarding odds of 8-1. The

Sporting Life

145

accused Fallon, along with Top Cees' trainer Lynda Ramsden and her husband Jack, of cheating. Fallon and the Ramsdens sued; the paper failed to prove its case, and was forced to pay £195, 000 in damages, as well as costs. More recently, Fallon was the most prominent defendant in a race-fixing trial arising from an expensive investigation by the City of London police. The prosecution's evidence had many flaws â among them that, for the races under investigation, Fallon's winning percentage was actually higher than normal. The case collapsed.

In

Genius Genuine

, Chifney recalled that Escape was a âstuffy' horse â one who needed plenty of exercise â and that the first race had toughened him up for the second. Escape was capable of putting in disappointing runs, and Chifney had shown himself a good judge of when they would take place. In the Oatlands handicap that year, he had chosen to ride Baronet, the eventual winner, instead. There was a horses for courses factor too: Escape had run some of his best races over the Beacon Course. At worst, it appears that Escape's connections were guilty of failing to

communicate to the betting public that their horse might not be at his best for the first, 20 October race.

The Prince, albeit after telling Bunbury to deal with Chifney âas you think proper', stuck by the jockey. According to Chifney, Prinny's words were: âChifney, I am perfectly well satisfied with your conduct since you have rode for me, and I believe you have discharged your duty like an honest, faithful servant, and although I shall have no further occasion for you, having ordered all my horses to be sold, I have directed my treasurer to continue during my life to pay you your present salary of two hundred [guineas] a year.' Having received this verbal and financial tribute, Chifney concluded that the Prince was, no matter what others may have been saying, a great man. âLanguage cannot describe my feelings on hearing this generous communication. I bowed and retired in silence, beseeching at the same time in my heart the Almighty to pour down his choicest blessings on a Prince whose magnanimity and goodness of heart induced him graciously to condescend to give protection and support to an unfortunate injured man, who but for this act of benevolence must otherwise have starved with his wife and children and who with them are bound to pray for such a generous benefactor.'

Chifney did not conduct his life thereafter with the humility that this encomium implies. Two hundred guineas was a sizeable professional's salary, and Chifney could carry on working as well, because the Jockey Club did not have the power, which it would later assume, to eject (âwarn off') miscreants from racing altogether. Unfortunately, Chifney had an extravagant nature, and descended into debt. In about 1800, about nine years after the Escape scandal, he asked for and received permission from the Prince to sell the annuity. This was when Andrew Dennis O'Kelly became involved in the affair.

You will have noticed that, despite the stipulation in his uncle's will that he should abandon racing, Andrew continued to take part in the sport. He was never as serious about it as Dennis

had been, but he raced up to seven horses during various seasons in the 1790s, and he also owned horses in partnerships â with the Marquess of Donegall, and with the Prince of Wales.

146

One of the mementoes of their continuing relationship is an 1801 letter from Andrew to George Augustus's equerry: âI have endeavoured to select some venison out of my park at Cannons which I hope will prove worthy the Prince's acceptance. I have sent it by this day's coach directed to you and request you will do me the favour to present it with my most respectful duty to His Royal Highness.'

In 1800, Donegall took on Chifney as a groom. When Chifney sold his annuity to Joseph Sparkes for 1, 200 guineas, someone had to offer security that Sparkes would get his yearly payments in return. Donegall said that he, being a marquess, could not do it, and asked Andrew to underwrite the sum instead. What followed was inevitable. The money went to Sparkes for a few years before drying up, and the annuity became another subject for litigation. In 1813, Andrew wrote that âthe holder of the annuity wishes to resume proceedings against me in the Court of Common Pleas'. Two years later, Andrew settled a sum on George Sparkes (to whom Joseph had assigned the annuity); a year after that, he deposed that the annuity was among Donegall's debts. It was another Donegall/O'Kelly mess.

The lump sum of 1, 200 guineas gave Chifney only temporary relief. Defaulting on a payment of £350 to a saddler called Latchford, he was sent to the Fleet, where he died in 1807, aged fifty-three. He left behind the design for the âChifney bit', ignored by the Jockey Club at the time but later to become standard equipment in racing stables. Aimed at controlling highly strung horses, the bit gives handlers a firm control of the horse's jaw.

It was apparent to the press at the time that the 1792 sale of the Prince of Wales's stud marked the end of an era. In its 13 March issue,

The Times

observed:

This was a melancholy sight to the whole kennel of black legs. Here end the hopes of royal plunder. Not even so much as a foal is to remain in his Highness's possession. The Turf is to be considered as a spot no longer tenable; and deserted by the Prince, it will soon be abandoned by every other gentleman in the kingdom.

Indeed, of late years, so much roguery has been practised, that there was no dependance to be placed on the horse or his rider â a pill of compounds given on the morning of running â a jockey purposely losing his weight, and many other tricks which lie in the power of the groom and the rider, without the possibility of detection, laid gentlemen so much at the mercy of their menial servants, that nothing short of ruin could be the consequences of a man of fortune attaching himself to Newmarket. The sale of the Prince's stud, it is therefore to be hoped, will be a good precedent for many more of a similar nature.

The Duke of York [Prinny's brother] was there, and bid for several of the horses. The public, no doubt, would naturally have hoped with us, that at a time when the Prince of Wales had seen the imprudence of keeping up a very large Turf establishment, the Duke of York would have followed his example; especially at a time when the friends of his Highness allege in Parliament that £37, 000 a year, added to his other revenues, is not sufficient.

Trends are hard to spot as they begin, but

The Times

was prescient here. The era of Eclipse and O'Kelly â the era when Dennis and the likes of Lord Egremont and the Prince of Wales could be rogues together on the Turf â was over. A new era, of structured and regulated racing, was arriving. That does not mean that skulduggery disappeared. As we shall see, it got worse: more

professional, and more vicious. It made one nostalgic for Dennis, the

jontleman

rogue.

In 1793, a

Sporting Magazine

correspondent (probably John Lawrence) was nostalgic already:

The zenith of racing popularity, when the laurel of victory was disputed, and in eternal competition, among a Duke of Cumberland, a Captain O'Kelly, a Shafto, and a Stroud. There are, tis true, now in health and hilarity, some few of the sportsmen who then graced the turf with their presence and their possessions; they well know how gradually the turf has been declining from the splendour of those days, to its present state of unprecedented sterility. Racing, like cocking, seems to have had its day (at least for the present generation).

Of the late D. O'Kelly, Esq, it may be very justly acknowledged, we shall never see a more zealous, or a more generous promoter of the turf, a fairer sportsman in the field, or at the gaming table. In his domestic transactions he was indulgently liberal, without being ridiculously profuse; and he was the last man living to offer an intentional insult unprovoked, so he was never known to receive one with impunity. In short ⦠he was not in the fashion now extant.

139

For writing this attack on many of his fellow members, Pigott, you may recall, was invited by the actual Jockey Club to withdraw.

140

Much as racing enthusiasts say of the Duke of Cumberland, in effect: âYes, he butchered a great many Scots; but he did breed Eclipse and Herod.'

141

Whose best-known achievements include Regent's Park and Regent Street, as well as the remodelling of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton.

142

See chapter 18 and colour section.

143

Allowing jockeys to bet invites suspicion at best and corruption at worst. The Jockey Club eventually banned the practice in 1879.

144

The politician and playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, author of

The Rivals

and

The School for Scandal

.

145

Later merged with the

Racing Post

.

146

A typically complicated arrangement concerned a mare called Scota. Jointly owned by Andrew and Prinny, Scota went to stud on the understanding that Prinny, paying an annuity for the privilege, would breed from her. When he sold his racing interests, he asked for her back.