Eclipse (30 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clee

The Sporting Magazine

, which contained many anecdotes about Eclipse, Dennis O'Kelly and their contemporaries.

T

HERE WAS ANOTHER COMMON

interest in the lives of the O'Kelly family and the Prince of Wales: the painter George Stubbs (1724â1806). It may have brought them together as agents behind a puzzling episode in Stubbs's later career.

Some time after 1790, a âgentleman' â his identity as mysterious as that of the anonymous nobleman who commissioned Mozart's

Requiem

â called on Stubbs with a proposal. It was to paint, in the words of the prospectus that appeared in

The Sporting Magazine

, âa series of pictures [portraits] from the Godolphin Arabian to the most distinguished horse of the present time, a general chronological history of the Turf specifying the races and matches and particular anecdotes and properties of each horse, with a view to their being first exhibited and then engraven and published in numbers'. The gentleman, identified to the public only as âTurf', said that he had deposited with a banker the sum of £9, 000, on which Stubbs could draw as required.

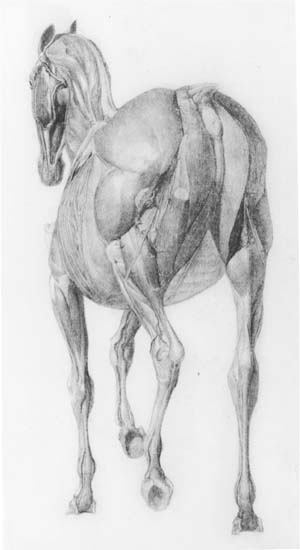

Stubbs was approaching his seventieth birthday. Born the son of a currier (someone who dresses leather) in Liverpool, he had largely taught himself his artistic techniques, a process that had included dissecting horses for eighteen months in

Lincolnshire. He rented a cottage in the village of Horkstow, where, assisted by his very tolerant common-law wife Mary Spencer, he anatomized a series of equine corpses. He bought each specimen alive, bled the horse to death, injected the arteries and veins with wax or tallow, suspended the body from an iron bar, and dissected and drew it for six or seven weeks, until it was so cut up and putrefied that he needed to move on to the next one. His first biographer, Ozias Humphry, gave an example of Stubbs's technique: âHe first began by dissecting and designing the muscles of the abdomen â proceeding through five different layers of muscles till he came to the peritoneum and the pleura through which appeared the lungs and the intestines â after which the bowels were taken out, and cast away.' Airless, noisome, and thick with bluebottles, that room would have displeased today's health and safety inspectorate.

When Stubbs arrived in London, towards the end of the 1750s, he quickly made his mark. His fine portraits, and his peerless paintings of horses and other animals â far in advance of previous works in the genre â put him in great demand among wealthy patrons. But interest in his work declined towards the end of the 1780s; and Stubbs, who was uncompromising and prickly, had a difficult relationship with the recently established but influential Royal Academy. The offer from âTurf' of £9, 000, attractive in itself, came with the bonus of an opportunity to promote the career of Stubbs's son, George Townly Stubbs.

An advertisement for the

Review of the Turf

appeared in

The Sporting Magazine

of January 1794. Dedicated âby permission to His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales', the

Review

would be

an accurate account of the performance of every horse of note that has started from the year 1750 to the present time; together with the pedigrees; interspersed with various anecdotes of the most remarkable races; the whole embellished with upwards of 145 prints, engraved in the best manner, from original portraits of the most famous racers, painted by G. Stubbs, RA, at an immense expense, and solely for this work.

From

The Anatomy of the Horse

(1766) by George Stubbs. Stubbs paid greater attention than had any previous artist to horse anatomy. However, not all experts believe his representations to have been consistently accurate (page 276).

The whole to be published in numbers, each containing three capital prints, 20 inches by 16, in addition to three smaller, engraved from the same subject.

An elegant house is open in a central situation, under the title of the Turf Gallery, to which subscribers have a free admission.

Stubbs would produce the 145 or more paintings, to be exhibited at a gallery in Conduit Street, off Hanover Square. George Townly would make engravings from them for prints to be exhibited alongside the paintings, and to be available for purchase. The prints would also appear, in large and small sizes and three at a time, in successive numbers â a partwork, we would call it â of the

Review of the Turf

.

Stubbs and his anonymous backer knew all about segmenting the market. They offered various methods of purchase: you could buy the whole lot of pictures in advance, or you could buy single numbers, or single prints. At the time of the advertisement, there were already sixteen paintings on show in the gallery. One of them was of Eclipse, and another of his sire Marske. There were, however, never any more than those sixteen paintings, and just one number of the

Review of the Turf

appeared. Perhaps the subscription figures were disappointing? In any event, the £9, 000 promised to Stubbs did not materialize.

The Prince of Wales and Andrew Dennis O'Kelly have both been associated with the

Review of the Turf

. The Prince was already a patron of Stubbs's work. Among his commissions was a portrait, showing him on horseback, with two terriers running ahead, by the Serpentine in Hyde Park. According to Stubbs's biographer Robin Blake, Prinny's obesity is âcarefully concealed'. Judy Egerton, in her magnificent

Catalogue Raisonné

of Stubbs's works, viewed the portrait differently, brusquely summarizing it as âan overweight bully riding a long-suffering horse'. The two Stubbs

experts arrived at varying conclusions too (though amicably) about the funding of the

Review of the Turf

. Blake agreed with the suggestion, advanced by others before him, that âTurf' was George Augustus, the Prince of Wales; hence the reticence â shown both by Ozias Humphry and by âT.N.', Stubbs's obituarist in

The Sporting Magazine

â over the patron's identity. The Prince would have wanted to be discreet about his association with a business venture, and following the Escape affair, in which he had been accused of setting up a betting coup,

147

he was not enjoying high esteem among the racing set who would be Stubbs's main customers. His indebtedness would also explain the non-appearance of the funding.

Holders of this theory, Judy Egerton suggested, may have fallen into the â

Great Expectations

fallacy' â the belief that a mysterious benefactor must be a grand personage. She advanced a different notion, with support from David Oldrey, former deputy senior steward of the Jockey Club: that âTurf' was Andrew Dennis O'Kelly, in a surreptitious ploy to hype his stallions. Oldrey's principal evidence is that Dungannon, Volunteer and Anvil, the three contemporary stallions in the first

Review of the Turf

exhibition, all stood at the O'Kelly stud. Dungannon may have been worthy of an appearance in the

Review

(though eventually his record as a sire was disappointing), but Volunteer and Anvil were unproven, and sat oddly in a collection that also featured indisputable Thoroughbred giants such as the Godolphin Arabian, Marske and Eclipse. Of Anvil, the catalogue copy said that he âmay be ranked amongst the best stallions of the present day, and from the cross of the Eclipse mares in Mr O'Kelly's stud, with the blood of King Herod, much may be expected from this horse'. This was hype, and Andrew, and his father Philip, would have been embarrassed to be revealed as the authors of it.

To back up this view, Egerton pointed out the unlikelihood

of the Prince of Wales, with business to transact with Stubbs, leaving his apartments in Carlton House to visit the painter in Somerset Street: he would have issued a summons instead. True; but the Prince could have commissioned an associate â perhaps Sheridan, who acted for him during the Escape affair â to pay the visit on his behalf. In response to Egerton's second argument, that Prinny was in no position to offer advances of up to £9, 000, one might point out that an inability to match his expenditure to his financial circumstances was Prinny's regular failing. His racing interests were also represented in the first group of paintings and prints: Anvil had run under his colours; and there was also Stubbs's

Baronet at Speed with Samuel Chifney Up

, portraying the horse and jockey who had won for the Prince the 1791 Oatlands Handicap.

The O'Kelly papers do not help us, so we fall back on speculation. We have seen enough of the O'Kelly way of doing business to suggest a compromise solution to the

Review of the Turf

mystery: that there was a partnership of some kind between the Prince of Wales and Andrew. The arrangements would have been exceptionally complicated, involving breeding rights at the O'Kelly stud and various other considerations. However, subsequent events intervened. The Prince, engulfed in scandal and debt, sold his racehorses; the O'Kellys found that they could not offload the mares at their stud; the outbreak of war with France caused an atmosphere of financial uncertainty. The ambitious project collapsed. Andrew continued to acquire work by Stubbs nonetheless, and by 1809 he owned, according to John Lawrence, one of the largest collections of the artist's work.

Stubbs's portrait of Eclipse for the

Review of the Turf

is a copy of his 1770

Eclipse at Newmarket, with a Groom and Jockey

, which hangs now in the Jockey Club Rooms in Newmarket. (The 1770 original is in private hands.) In Judy Egerton's expert view, while Eclipse is âfinely modelled' in the later version, âthe handling of the groom and jockey is more awkward', and the paint surface is

âthin'. In

The Sporting Magazine

, the two human figures were described as âthe boy who looked after [Eclipse], and Samuel Merrit, who generally rode him'. Whether the jockey really was Samuel Merriott is discussed elsewhere.

148

The labelling of the adult-looking groom as âthe boy' was a mark of the status of stable staff; today, they remain âlads' and âlasses'.

A print of this picture (see this book's colour section) hangs above my desk as I write. Eclipse, saddled, stands before a square brick building with a pitched roof of yellowish tiles. We know, from a landscape study by Stubbs of the same scene, that the building is the four-miles stables rubbing-house at the start of the Newmarket Beacon Course, and can therefore speculate that the scene is the prelude to what may have been Eclipse's toughest race, his match of 17 April 1770 against Bucephalus.

149

Eclipse has a cropped tail and a plaited mane. Light makes gleaming patterns on his chestnut coat. His body is long; he has an athletic elegance. Behind him, the Newmarket heath stretches towards a modest row of trees. The horizon is a quarter way up the picture, and the big sky above is springlike, with massing white and dark clouds.

The âboy', smartly dressed in a black coat, holds Eclipse's reins, and looks over his shoulder, with what may be apprehension, at the jockey. This groom has had to get Eclipse to Newmarket, keep him fed and watered and healthy and happy, and present him in perfect condition on the day. Now he transfers the responsibility, and all he can do is wait and watch. Eclipse is looking at the jockey too; and Merriott â if it is he â returns the look, calmly. Without that calm, he could not do his job â no matter how good his horse may be. He wears the red colours with a black cap that Dennis O'Kelly had appropriated from William Wildman on buying Eclipse; he carries a whip, but as if reassuring the horse

he will not use it, and he does not wear spurs on his boots, reminding us that Eclipse ânever had a whip flourished over him, or felt the tickling of a spur'.

150

As so often in Stubbs's work, what we witness here is a quiet, contemplative moment apart from the action. Every element of the scene is beautifully placed, so that, in spite of Merriott's striding posture, the painting conveys stillness. The horse and his rider are about to offer a demonstration of greatness, in front of cheering crowds. But Stubbs does not show these jubilant events, either in this or in any other of his paintings. When he does show a race, in his portrait of Gimcrack at Newmarket, the contest is only a trial, climaxing in front of a shuttered stand; it has taken place in the past, and is in the background of the picture, while the foreground has Gimcrack with his stable staff at the rubbing-house. There is in Stubbs's paintings a very British mix, apparent too in the poetry of Tennyson and the music of Elgar, of grandeur and melancholy.