Edge of the Orison (29 page)

Read Edge of the Orison Online

Authors: Iain Sinclair

(2) Thomas Eastoe Abbot:

The Triumph of Christianity

. 1818. ‘The Author of these Poems having received a copy of Mr Clare's poems through his Friend Mr Sergeant begs leave respectfully to present…’

(3) John Bunyan:

Holy War

. 1810. With Clare's signature. The name of the previous owner, John Hunt, has been struck through, cancelled.

(4) Lord Byron:

Don Juan in 5 Cantos (A New Edition with Notes)

. n.d. (1818). With three engravings after Corbould. A drowning scene: storm-tossed beach, two women, sprawled man. A prevision of Shelley, mourned by Mary and Jane Williams?

And, like a wither'd lily, on the land

His slender frame and pallid aspect lay

As fair a thing as e'er was form'd of clay.

(5) William Cowper:

Poems

. Clare's signature: ‘Helpstone 1819’. And the additional signature of Sophia Clare, his sister. Shared ownership, shared purchase?

(6) Daniel Defoe:

Robinson Crusoe

. 1831. With the inscription: ‘Frederick Clare. The gift of Mr. Taylor. Feb 15th 1834.’

(7) Thomas Rowley:

Poems, Supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley, & others. In the Fifteenth Century

. 1757. Published by T. Payne. Clare followed up on his mother's gift from Deeping Market, the Chatterton handkerchief. Pastiches, forgeries. He learnt the art of passing off Elizabethan imitations on unsuspecting (or indifferent) editors of almanacs.

(8) Izaak Walton:

The Compleat Angler

. A handsome beast. Decorative boards.

(9) James Thomson:

The Seasons

. 1818. A new edition of the fatal volume, Clare's introduction to poetry. Carried into Burghley Park.

Volume after volume reveal the history, slanting ownership signature, of a man who refused to soil books with annotations, marginalia, challenges to false authority. Clare was no Graham Greene, ‘improving’ dull texts with inventive scribbles, in order to boost future sale prices.

The librarian summoned us. The ‘Journey out of Essex’ microfilm was ready. Winding it through a lightbox, we saw a spread of words: different inks, different spacings, boxed footnotes. Nothing wasted. Clare's narrative strides: it ploughs the field, knitting with barbed wire. The act of composition is physical, you feel the nib gouge at the paper. The escape from High Beach is re-enacted in blocks of vivid prose: ‘Reccolections of the Journey from Essex’. Script slants against the breeze. As the days pass, so lines draw closer together; breath comes harder, final flourishes are less flourishing. Clare limps but his story pushes remorselessly towards its conclusion.

Viewing the screen feels like a betrayal: of author and quest. We have been presented with Clare's secret before our own walk is concluded. The key for Ramsey remains obscure. No connection has been discovered between Anna's family and that of John Clare.

The meeting with Alan Moore, the circuit of the asylum he offers, is our farewell to a project that defies resolution. And which may, very soon, be consigned to the storage boxes and dead files of Northampton Library. Marked: ‘incomplete’. Abandoned.

The Sun Looks Pale upon the Wall

All Saints' Church in Clare's day was an island, raised above a dirt road by the height of a coach. The present railings, an annoyance, are replicas of the originals; church and business (the caves of Gold Street) were kept apart. Northampton, with its taste for scouring fire, has a long tradition of meaningless feuds, human barbecues. Dislike of successful incomers. On Good Friday, 1277, a number of Jews were drawn ‘at the horse-tail’ to a chosen place outside the city walls, and there hanged. The following year, the Jewish community was again attacked; property forfeited, men executed on suspicion of clipping and forging: stoned to death.

Twin alcoves, I'm not sure which of them Clare favoured, are worn smooth. They are popular with loungers, tourists wanting to sit where Clare sat: in the local version of Wilhelm Reich's orgone accumulator. A device for concentrating energy, sexual potency. The slots are tall and arched, bald as the peasant poet's skull, his double-decker dome. Stone is warm, shaped by human weight like an outdoor privy: buttock indentations in the polished seat.

We're early. We go inside to inspect another Clare trophy, another severed head: gilded, beaked like a parrot, dumbly prophetic. Friar Bacon's automaton willed to silence. A penny-swallowing toy in memory of Clare's days as a public beggar. Allowed his liberty, a walk from the hospital, the poet filled his alcove, behaving, pen in hand, like a flesh statue. For a plug of tobacco, the price of a pint, he would write to order: a fortune-telling machine. Stout Farmer Clare, strolling down Billing Road (remembering Bachelor's Hall?), takes his place, benevolent gargoyle, in the otherwise incomplete church.

Charles II, high above the portico, is crowned with a garland of oak leaves in memory of his escape after the Battle of Worcester.

His flight from England. Now he can fly again, a second Bladud, a stone Icarus. Alan Moore has written about a Second World War bomber crashing on this street: ‘a great tin angel with a sucking chest wound fallen from the Final Judgement’. It skidded into the Market Square, an object of interest to the gathering populace; only one of whom, a cyclist, was slightly injured.

George Maine drew Clare – leggings, waistcoat – perched in his alcove; quill in one hand, notebook in the other. Top hat on the ground: available for alms, a dropped coin. Renchi, as we wait for Alan Moore, duplicates the pose: writing and sketching. I sneak a glance at the page. ‘Northampton ANNA,’ it says. Anna Sinclair, so far as I know, has never been to Northampton. Nor stayed in an ibis. The cultural deprivation in her life is shocking.

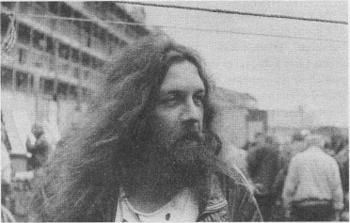

Alan manifests: curtain of hair tossed back, snakehead stick brandished. A wand. His black vest is rimmed with body salts. A sticky day. He's walked from his home, out to the north, above Abington Park. Alan's property faces a mini-anthology of poetic terraces: Milton, Byron, Shelley, Moore, Chaucer. An eccentric gathering: Tom Moore being the odd man out. Alan says that, in years to come, guide books will have Moore Street named after him: creator of

From Hell

and

Swamp Thing

, convener of

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

. After all, he got his start at Northampton Arts Lab with poetry gigs. He remembers Anne Tibble, the Clare scholar, receiving a round of applause for a reading laced with gracefully handled obscenities. Her gesture to the times, the Non-Swinging Seventies.

They shake hands, the artists; Renchi's sheet-washing, bed-making, paint-smeared digits and Moore's silver claws. Alan's a post-ironic scissorhand, tin man, jumped from the pages of Marvel comics. John Dee's roadie made good. Scryer, tapper of tables, voice-catcher: mythologist. Fingers flash in dazzling thimbles; a heavy-metal scrap of rings pulls him, effortlessly, through the hill town's sluggish magnetic field.

We shamble down St Giles Street, a tour of the Guildhall (decorations by a Moore ancestor, amateur artist, professional drinker):

before our assault on St Andrew's Hospital. But first Alan sidetracks us into the Wig & Pen, a wannabe lawyers' pub, formerly known as the Black Lion. Before this

Rumpole of the Bailey

makeover, there was a ceiling painting, spirits of place: John Clare acknowledging Alan Moore. An art student's unknowing variant on Rippingille's conversation piece,

The Stage Coach

. A lick of paint obscures Northampton's culture heroes; they've vanished. And, in vanishing, have acquired the dignity of legend; something forged in tipsy memory.

Revamped pub signs are the tarot pack of county topography. Moore rescues the Labour in Vain, the hostelry Clare passed on Enfield Highway; where ‘a person coming out’ set him on the right track for the Great North Road. In

Voice of the Fire

, Alan places this refuge, which has never been found, outside time; an anomaly located by solitary travellers in states of crisis or extreme anxiety. A false oracle of the English road.

The car-burner Alfie Rouse, heading out of London towards the Northampton field where he will smash the skull of a man picked up in transit, visits a roadhouse called the Labour in Vain – in which he encounters an ‘old tinker with a funny stand-up hat’: the misplaced Clare. Eric Robinson and David Powell, editors of

John Clare by Himself

, admit that they have ‘no knowledge of a public house at Enfield Highway called the Labour in Vain’.

Robson's Directory

(1839) lists nine pubs. The mysterious ‘Labour in Vain’ is not one of them.

In less confident towns, we might offend the eyes of sober citizens; crowds would part, squad cars slow. Not here, not now. We've erred on the side of discretion, anonymity. Picture it. The black-vested Moore with his swinging stick, silver fingerstalls. He claws back a damp curtain of thick hair, reddish-brown hemp of Jesus length. Salt-and-pepper beard teased out like a Robert Newton pirate: Blackbeard without the burning tapers. Advancing through broken suburbs, he's the dead spit of one of the ‘Vessels of Wrath’; the fire demons depicted in Francis Barrett's

The Magus (or Celestial Intelligencer)

as ‘Powers of Evil’.

The Magus

is the magical primer

Moore searched out in a Princelet Street attic, years before; a Whitechapel fantasy, a film. In performance, he became that thing: ‘The worst sort of devils are those who lie in wait, and overthrow passengers in their journeys.’

We straggle up the steady incline, away from the town centre: a carnival of mountebanks fleeing the plague. Expelled jugglers, confidence tricksters. Renchi: blue bandanna, long shorts, lightly bearded. Moore: striding out with upraised staff. And your reporter: sun-bleached cap from fisherman's hotel, desert jacket. A spook embedded in the madness. Traitor. Manipulator of fictions.

Moore announces that on his fiftieth birthday he will retire from mainstream comics, the grind. Give himself over to the twin disciplines of magic and the writing of prose, a sequel to

Voice of the Fire

. He has already signed away future income from Hollywood; the films of

From Hell

and

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

were nothing but aggravation. Court cases loom, million-dollar plagiarism suits brought by disgruntled careerists who failed to understand that invention has no copyright. The Faustian contract between graphic novels and movies is based on mutual cannibalism, brain-sucking rip-offs, canny lifts from the dead or the powerless.

Ghostly legions of the reforgotten know that remakes are the only true originals.

‘There is a magical virtue,’ writes Barrett,

being as it were abstracted from the body, which is wrought by the stirring up of the power of the soul, from whence there are made most potent procreations, and most famous impressions, and strong effects, so that nature is on every side… and by how much the more spiritual her phantasy is, so much the more powerful it is, therefore the denomination of magic is truly proportionable or concordant.

As we walk, Alan unfolds, in a way that only a lifelong victim and lover, bridegroom of the town, could do, his account of certain buildings, certain people. Anecdotes. Family reminiscences. He grants Clare a chapter in

Voice of the Fire

: an exercise in ventriloquism pastiching the journals. But nothing carries you further, or deeper, than the poet's own prose; the slanted script we experienced in the library. The hospital was always the conclusion of the walk from London; a purgatory in which to shake free of identity, the compulsion to scribble. Spoil paper. Northampton was a good place for the eyes to lose their inward fire.

There was never to be a second escape. Mary was gone. Madness was the loss of her, the missing portion of Clare's soul. In a grubby asylum notebook, he inscribed the names of one hundred and fifty women. Mary Joyce was omitted. He sat at a window, for hours at a time, attempting to recall those faces, the lost harem of beauties; admired, forgotten.

William Knight, one of the asylum staff, a good friend, helped to preserve the Northampton poems, troubled fragments. The music of the Nene infiltrates the verse; rhythms of water, water memories.

Love's memories haunt my footsteps still,

Like ceaseless flowings of the river.

Its mystic depths, say, what can fill?

Sad disappointment waits for ever.

A second walk was impossible, flight pointless. There was nowhere to go. In two days, Clare could have been back in Northborough, having travelled across soft country, tracking the river. But he refused to consider escape, even when other inmates discussed their plans. That book was written. A new journey would undo it. Northampton was an occulted principality: the asylum its seminary, Dr Prichard its magus. Prichard could draw invisible wires from men's heads. He knew their thoughts because he planted them. Composing delusions, he was benevolent but absolute. Two runaways got as far as Hertfordshire before they were captured and brought back. ‘I told you how it would be, you fools,’ said Clare. He could wander freely through town, fields and woods, to Delapre Abbey: because he was psychically tagged. Branded. Watched.